By Kevan Garecki

It’s no secret that the horse transport industry attracts people who think in terms of a fast or easy buck; the rate of start-ups claiming to be “horse haulers” is testament to that. The number of disreputable haulers makes the choice even more difficult. So, what’s a caring horse owner to do when the commercial horse transport landscape is as alien as the far side of the moon?

The prevailing climate of standards for Canadian motor carriers is uneven at best. Apart from applying for and receiving a National Safety Code Carrier Number, and adhering to inept 50-year-old transport laws that have almost nothing to do with horses, there are virtually no formal regulations surrounding carrier performance as it relates to livestock. There is only the meagre legislation that can be enforced by the Canadian Food Inspection Agency, the enforcement body responsible for overseeing livestock transport in Canada. Physical aspects such as loading density, vehicle configuration, and other sundry housekeeping details are clearly defined, but in terms of minimums. Vehicle safety and licensing are governed at the provincial level and enforced by some policing body, such as the Commercial Vehicle Safety and Enforcement branch in British Columbia. There is no governmental control over who may haul what, nor any proof of competency required.

Cheap isn’t always a good deal, and a high price is no guarantee of quality. Newcomers to the transport scene will often compromise their rates, make circuitous detours to fill their trailers, and make other concessions in efforts to increase trip revenue. Experienced carriers already know these tactics are ineffective, and most importantly, the horses end up paying the price. Therefore you, the consumer, are solely responsible for ensuring well-informed decisions are made on behalf of your horses. Become familiar with the preferable answers to pertinent questions, and trust your gut; if it doesn’t feel right, find out why or find another carrier.

Here are some of the questions to ask a prospective commercial transporter, whether your horse will be travelling to a major event or just across town.

What does your contract entail?

Carriers who’ve been at this for a while learn that they need to offer a comprehensive contract that clearly outlines the following:

- Complete information on who is offering the horse for transport, and the owner, if this is a different person or entity.

- Contact information for delivery — who is expected to receive the horse and who is authorized to sign off on the contract when the horse arrives.

- Clearly defined payment requirements and options, including refunds in the case of nonperformance of the carrier. The contract may also state extra costs such as charters, special needs, and other unique situations.

- A description of the horse that is clear enough to identify the horse. This is essential for insurance purposes, and if such a situation ensues, that description must be clear enough for someone not involved in the transport to pick that horse out.

- A definitive description of the accommodations the horse will be transported in. If you’re paying for a box stall, you want to know your horse will be held in one.

- Extraneous or extra materials, equipment, and gear. If you’re shipping tack lockers, blankets, extra hay, etc., all these items should be clearly listed and valued. You may be asked to provide self-insurance or pay for the additional space these extras will take.

- A clearly defined set of parameters regarding responsibility, conditions and terms of transport, payment, and other compensation or risks. It’s not uncommon for this section to span an entire page in very fine print.

Carriers purchase general liability and specified perils policies, but those policies typically benefit the carrier. The coverage becomes more replete as the carrier gets years under their belt; it’s not uncommon for well-established companies to hold $5,000,000 umbrella policies with coverage for veterinary costs, layovers, and even alternate transport in case of breakdowns. This coverage isn’t easy to get, nor is it cheap.

For an important perspective on carrier insurance, remember that it’s for the carrier. You will seldom benefit from whatever coverage a carrier has. Their insurance protects them, not you.

If your horse is of exceptional value, you will almost certainly be asked to first provide proof of such value and to carry your own policy. Even the best policies have realistic value ceilings, and while those will cover most horses, they usually limit between $10,000 to $50,000 per horse. Ask the carrier what their per capital ceiling is and be prepared to provide additional coverage if needed. This is not uncommon; an owner can get a transport rider for their horse in cases such as this.

What are your payment requirements and options?

With credit card companies raising rates, smaller companies looking to trim their administrative overhead may refrain from accepting credit cards for payment. Interac e-Transfer is very common, some will take cash or cheques, but be sure to confirm the form of payment before booking. Most carriers require payment on arrival unless prior arrangements have been made.

It’s common for carriers to require a portion of the transport fees in advance, for costs of things like customs brokers, layovers, or other overhead. Deposits must be returned within a reasonable length of time, in the case of non-compliance or failure to perform on the part of the carrier; that reasonable time is generally considered to be one business week. Deposits typically equal the projected costs the carrier may have, such as brokerage and filing costs in the case of international shipments, and no more than 50 percent of the transport cost quoted to you. There is often a discussion about what is considered a deposit or prepayment. Prepayment may consist of payment after the horse is picked up, but prior to delivery; whereas a deposit is a sum required on booking in a case where the client may not be known to the carrier. The latter has sadly become necessary due to last minute cancellations (usually for a cheaper rate and/or a faster delivery), which leaves the carrier with empty spaces, and translates to lost revenue.

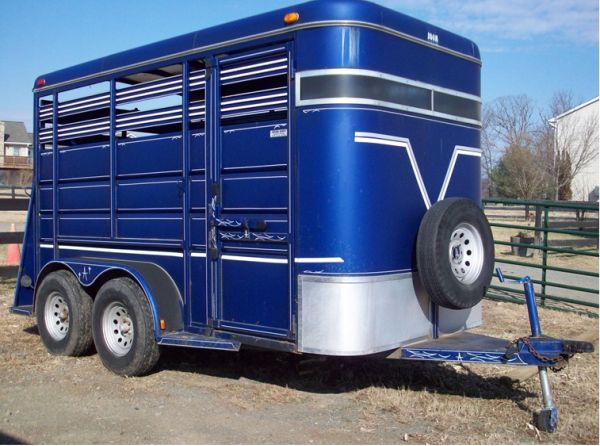

Carriers commonly require a portion of their fees in advance to cover overheads such as brokerage fees and layover costs, typically no more than 50 percent of the total transport costs. Photo: Clix Photography

How far ahead should I book?

The old adage about the best ones being the busiest is still true, so confirm pick up and delivery dates well in advance; this is especially important for international moves, as paperwork can take weeks to prepare. Don’t wait until the day or even the week before you need a ride for your horse. Even where carriers have regularly scheduled routes, trips can book up days or weeks in advance.

What configurations do you offer?

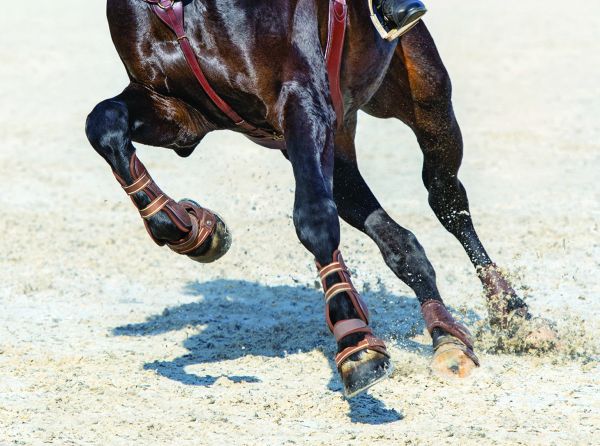

Box stalls are the least stressful, and I consider boxes essential for young and elderly horses, and those with special needs. “California” or “stall-and-a-half” is another common preference, especially for longer distances. Standing stalls are fine for hops up to a full day of travel, but longer trips should entail at least a stall-and-a-half or boxes.

Most commercial grade trailers have the capacity for alteration of stall lengths as well, thereby increasing the safety for both larger and smaller passengers.

The most common for professionals is the head-to-head design, which comprises most of the standing stall setups. Virtually all trailers the pros use can accommodate various stall configurations, and most larger rigs allow for entry and egress of any horse without the need to move another, although this may not be possible if the trailer is set up expressly for box stalls throughout.

Good quality hay should be available to every horse at all times, unless there is a medical reason to withhold it. Photo: Clix Photography

The rigs used by professionals can usually accommodate various stall configurations, the most common of which is the head-to-head standing stall design. Photo: Clix Photography

Another reason to ask about rig configuration is to ensure vehicle access. If the hauler shows up with a 15-horse highway liner and your driveway is only three meters wide and on a narrow road, you might need to haul your horse out to a marshalling point or load on the road. Most large carriers already know what their rigs are capable of, so they’ll confirm physical access anyway.

Angle haul trailers are not considered acceptable by professional carriers. The only exception to this might be for very short hops (no more than a few hours), or emergency situations. Angle haul trailers are just not in a professional carrier’s vocabulary. On long trips, angle hauls elevate the risk of injury, as horses may need to be loaded and unloaded to accommodate passengers along the way.

Can you provide several references?

It takes time to gain trust of elite trainers and owners, so the more prestigious the reference, the more assured you can be of professional work. Be wary of obscure references, it’s not uncommon for less reputable haulers to give phone numbers of their relatives, or even themselves. Check the references if you don’t already know them. Reputable clients align with reputable carriers, so you can rest easier knowing those clients make conscientious choices on behalf of their horses.

How are pickup and delivery times estimated?

While not a common question, it is a valid one. If your horse is loading with multiple others, he may spend time on board while they shuffle around town, or even detour between towns along the way. Find out where else they’re going and how long they expect to have your horse on board. Be conscious of detours; it’s easy to rack up hours if your horse is the first one on and the last one off, when the truck is zigzagging through regions. The latter is a common tactic among those who put extra revenue ahead of diligent care of horses. While some detours are unavoidable, they should not be lengthy.

Make sure you are informed of the pickup and delivery times, and the estimated time the trip will take. Photo: iStock/Romaoslo

What are your policies for special needs or charter trips?

All experienced carriers offer provisions for special situations, because they’ve encountered unique circumstances in the past. They can offer options based on past experience. Be aware that “special needs” almost always means “increased costs.” This is one area where quality doesn’t cost, it pays. Having a carrier who is experienced in unusual situations can mean the difference between a successful trip and a nightmare, for both horses and their owners.

Special needs can refer to active breeding stallions, pregnant mares or those with foals at side, quarantine cases, elderly or injured horses, and any horse with specific needs relating to transport and handling.

Special needs situations include transporting a breeding stallion, a pregnant mare or mare and foal, or an injured or elderly horse. These circumstances almost always mean increased costs. Photo: Clix Photography

A charter trip means your horse is the sole reason for the trip, such as emergencies and quarantine situations. This requires that the carrier dedicate a rig specifically for you, and usually entails a round trip. Costs are factored based on mileage or time needed, and reflect the sole dedication of equipment. It isn’t cheap, but this is not the time to haggle. You’re paying for more than the time your horse spends on that trailer; you’re paying for the expertise that ensures their safety in transit.

Can I contact someone en route?

This is an absolute must in my book. I don’t care if it’s two o’clock in the morning, I want to know that I have a number I can call, and that someone is going to call me back — soon. While larger companies may not give their drivers’ numbers out, they should at least have an emergency contact system available to you. The opposite is also true: If I have your horse on board, I need to know I can talk to someone at any time if your horse has a problem.

A text or email from the carrier at rest stops and trip milestones will keep the horse owner informed of progress and any changes to the schedule. Photo: Clix Photography

Can you provide updates?

A quick text or email at rest stops, border crossings, or other milestones along the way is not only professional, it’s just something that should be done. You’re not shipping lumber; you’re asking the hauler to care for a living being. Calls confirming delivery times, announcing delays, or other changes to the itinerary are a given; at no time should you be left in the dark about anything you need to know.

For example, except for short hops, I am usually in contact with my clients at several points along the journey. If the client is not present at pickup, I’ll advise when the horse is on board, and if necessary, revise the previous estimated time of arrival (ETA). Depending on trip length, I will have already outlined rest stops and provided an arrival estimate. I will advise ETAs with the receiving contact, and if the client is not at the delivery point, I will notify them once the horse has been safely tucked in.

What happens if my horse is injured or becomes ill on board?

This is one of a multitude of fears professional carriers have, and we develop safety nets wherever we can. From preventative measures to comprehensive support networks that include veterinarians if needed, reputable carriers strive to provide the safest environment for your horse. If they cannot contact you within a reasonable period of time, they may elect to call a vet; if this is necessary, you are legally responsible for any and all costs related to that call. If the carrier contacts you and you elect to decline veterinary intervention, then full responsibility for all consequences of that choice fall in your lap. This includes damage, risk, injury, or ailment to other horses on board, carrier personnel or equipment, and even the general public. An experienced carrier knows when it’s time for the vet, when they can intervene themselves, and what the associated risks are. Once again, this is where quality doesn’t cost, it pays.

What are my options if I’m dissatisfied with your service?

Another curious point about Canadian transport law is if you have a problem with a carrier, only after the hauling cost is paid can you take legal action against the carrier. If the carrier is late, fails to pick up, or shows up with your horse sweated up, although unfortunate, none of these situations is cause for compensation from the carrier. If your horse becomes injured, and such is provable as negligence on the part of the carrier, then you can seek legal action, but you still have to pay their bill first.

As carriers are not censored or even monitored with respect to customer satisfaction, there is little other recourse save the court of public opinion; but beware, spreading derogatory claims about anyone publicly can land you in a defamation lawsuit unless you have documented proof. You must have documents to prove your point.

This article is a brief introduction to some of the potential topics you may need to address with your carrier. In the nearly 50 years I’ve been in this business, my contract has grown exponentially, and I still encounter new situations. Considering all of these points will not guarantee your horses’ safety and comfort, but should at least minimize some of the margins by which disreputable haulers compromise that safety and well-being.

Housekeeping Habits of Reputable Carriers

Photo: Clix Photography

The following are basic guidelines well-known to experienced horse haulers.

- Bedding is required by law in every jurisdiction in North America. If the trailer has a bare floor when it shows up, lose their number.

- Hay is essential. If you’re worried about dust, use better hay. Yes that’s blunt, but hay should be available to every horse at all times unless there’s a medical reason to the contrary.

- Water must be available on longer trips. Most horses can survive quite well for a full day without water, and very few will drink water while in transit or water that is foreign to them. I don’t get too worried about water intake until the second day. After that I have a bag of tricks to get horses to drink (as does every other experienced carrier). I offer water at rest stops, and on longer trips water is available all the time. Shorter hops of under a day can usually eliminate this last step.

- Layovers for horses are essential after 20 hours; this is law. If your horse is expected to be travelling longer than that, the carrier should provide you with contact and location information on layover stops.

- If the trip exceeds two days, the horse is elderly, pregnant, has a foal at side, has a medical or physical condition for which transport can cause concern, or must be segregated from others, the only solution is a box stall. This is a firm rule with me, and I refuse to haul horses that fall into the above categories in any other fashion because the stress level on the horse is just too high to risk complications.

Photo: Clix Photography