Sponsored

Source: Acera Insurance

Brain bucket, crash helmet, head armour, noggin shade, bump cap. Protective helmets have many derogatory names and a long history of ridicule. For decades, hockey players’ sweaty locks flopped about as players slammed into the ice and were walloped by pucks. Skiers protected their brains from colliding with trees by pompom-topped toques, and cyclists wore a leather hairnet to protect their brains from smashing into the pavement. Horseback riders boasted trendy top-hats in the late 1700s, while the fashionable bowler was invented in 1849. Apparently, the bowler’s “tasteful design meant that it didn’t blow off easily.” Fortunately, protective headgear design and social acceptance have evolved.

Hockey players first adopted sleek leather head-warmers in the early 1900s. Hard-sided protective helmets subsequently appeared on National Hockey League players’ drenched heads in 1928 but were unpopular with fans and media. After a player died in 1968, helmets became more acceptable and in 1979, professional players were mandated to wear helmets. Today, before toddlers wobble about on a backyard rink, parents insist they don a helmet.

Downhill ski racers first sported biker-gang-like leather caps in the early 1900s to reduce their drag. Protective headgear eventually came of age and at the 1960 Olympics, skiers had to wear hard-sided helmets. However, recreational skiers were slow adopters and in 1990 non-racing ski helmets barely existed. Deaths of high-profile skiers made helmets more common, but hipness won the day. Helmet acceptance took off in the late 1990s when well-known snowboarding athletes replaced their slouchy toques with sporty helmets. By 2010, 76 percent of recreational skiers and snowboarders wore helmets and head injuries had decreased by 65 percent.

Cyclists started their helmet-wearing journey in the 1880s with distinctly unfashionable pith helmets. In the early 1900s, they succumbed to the leather craze and wore leather-strap contraptions into the 1970s. In the 1980s, the sport-specific Bike Bucket appeared. In 1987, the US Cycling Federation required helmets in all competitions; the Union Cycliste Internationale followed in 2003. Today, bike helmets are a necessary part of recreational cycling and many Canadian municipalities issue tickets to non-helmet-wearing renegades.

Protective riding helmets evolved at a similar pace, but helmet acceptance remains patchy in horse sport. In 1911, cork safety helmets were manufactured for the British Army. In the 1950s, flat racing associations mandated jockeys to wear skull caps. At the 1978 equestrian World Championships, a Team USA three-day event rider sustained a serious head injury when her velvet-covered hunt cap came off during a fall. This spurred the requirement for Pony Clubbers, event riders, and show jumpers to wear safety helmets and most do today when schooling or competing. In 2001, Ontario passed the Horse Riding Safety Act which stipulates that anyone under 18 has to wear a certified horseback-riding helmet. In 2012, competitive Canadian dressage riders were mandated to wear helmets in competition but today many still train in baseball caps. In 2019, Rowan’s Law was implemented in Ontario, mandating all coaches, parents, and athletes — including Ontario Equestrian members — to take annual concussion training. The law was implemented following high-school rugby player Rowan Stringer’s death from multiple concussions. Today, the Equestrian Canada rulebook states: “Any competitor may wear approved protective headgear in any division or class without penalty from the judge.”

But some riders and sports organizations hold different views. According to the 2022 National Cutting Horse Association rulebook, competitors must wear a cowboy hat and can only wear a safety helmet with advance approval of show management. Rodeo and reining are more progressive. Saddle bronc and bareback bronc riders, barrel racers, and reiners can all choose between a cowboy hat or protective helmet, and helmet acceptance is increasing due to high-profile deaths. However, with the exception of Ontario’s youth, non-competitive Canadian riders are not mandated to wear helmets.

Regardless, some horse associations and property owners have rules about helmet use and often they’re driven by insurance requirements. Mike King is a partner at Acera Insurance and addresses insurance claims for an extensive portfolio of equine industry clients across the country — including when head injuries are involved. King says, “Head injuries occur with disturbing regularity in horse sport and are avoidable in so many situations. It seems archaic to me that ‘fashion’ trumps common sense and safety. In the end, it’s not the rider who foolishly refuses to wear a helmet that worries me. It’s the rider’s wife, husband, child, or parent who may be burdened with a loved one who has suffered a head injury — or worse.”

Acera Insurance. Same great people, stronger than ever.

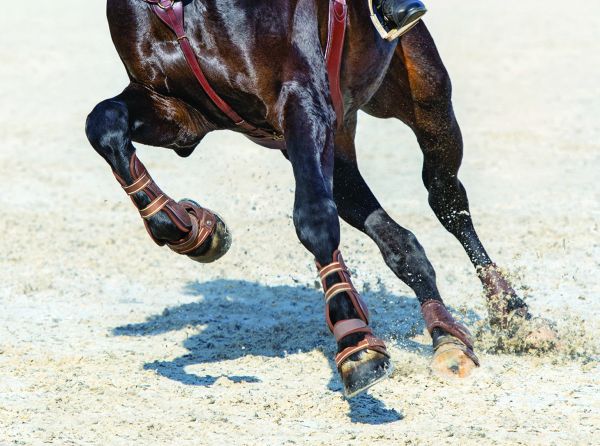

Photo: Shutterstock/Anzhelina