By Alexa Linton, Equine Sports Therapist

As I write this article, I am days into the arrival of my new pony Gwynna, the third member of my little herd, with a herd integration in our near future. It seems somehow fortuitous to be riding the various waves of emotion that this transition can present — trepidation, fear, anticipation, and uncertainty — as I unpack what it takes to successfully introduce a new herd member or move from a barn with horses on their own to one where the herd lives together. By virtue of my ongoing passion for horse track systems and species-specific horsekeeping, this topic is important. For those who want to shift their way of keeping horses but are getting stuck on how to do it, understanding how to manage the transition can be a deciding factor.

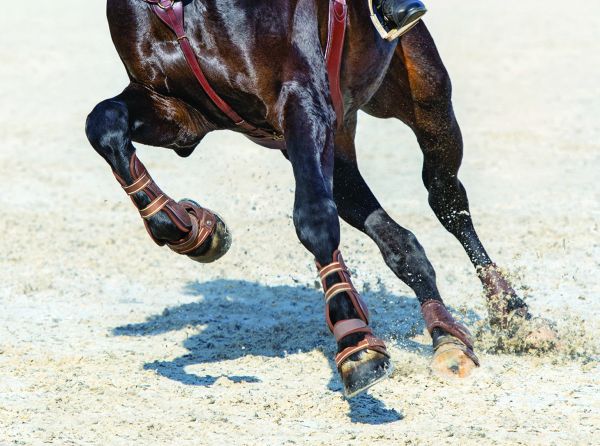

My main motivation for writing this article is to help horse people feel more comfortable making shifts that support happier horses. As equine behaviourist Lauren Fraser says, horses thrive with friends, forage, and freedom, in that order. Friends are first on this list because other horses are literally the most enriching, interesting, connecting, comforting element possible in a horse’s life. Horses are naturally social herd animals, wired for connection and community, much like humans. They thrive in environments where they can touch, interact, attune, play, groom, eat with, walk with, sleep with, and be with other horses. Even the most successful performance horse is wired this way.

Related: Compromised Welfare in Individually Housed Horses

Related: Get Your Horse On a Track System

Can all horses live in a herd environment? Sadly, no. Some horses, separated and isolated from other horses from a very young age and lacking in social skills, may never be able to live safely in the same area as other horses — but this doesn’t mean they can’t have healthy interaction over a safe fence-line. Fortunately, this is rare. Even with underdeveloped social skills, most horses can learn to live happily with other horses, and those that do benefit in countless ways physically, mentally, and emotionally. In this article we will look at how to integrate horses with varied social skills as successfully as possible.

Horses are social herd animals and thrive in environments where they can interact with other horses. Photo: Shutterstock/Liza Myalovskaya

First, let’s talk about the barriers to integration. If your horse has never lived with other horses and is currently living alone, take a moment to think of the reasons why. Your reasons may include fear that the horse might become herd-bound, exhibit dangerous or uncontrolled behaviour, or suffer potential injuries and create additional expenses. Perhaps you have a fear of change. Maybe your horse lives at a boarding barn that doesn’t offer group turnout, has no facilities supportive of shared living, or employs a restricted feeding regime. When we look closely, most barriers to herd living are born out of fear or a need for control. Yes, having horses in stalls and/or individual small paddocks can feel safer and easier, but who benefits? If we reflect on why we are choosing a certain way of horsekeeping, we might be more open to a change that prioritizes the species-specific needs of our horses.

Next, let’s talk about the nitty gritty of integrating horses into a herd. For the longest time, before my deep dive into the function of the autonomic nervous system, I employed the “pull off the Band-aid quickly” technique when it came to horse introductions. Putting horses together with very little preparation and hoping for the best was quite anxiety-provoking for all, including me. I now see the error of my ways, even with a well-socialized horse like my mare, Diva. With my newest herd member, Gwynna, I’m putting into action a slower and much more thoughtful approach gleaned from conversations about integrations with many trainers and professionals.

Related: Design a Better Horse Stall

Related: Podcast - Healthy Herd Integration with Josh Nichol

The first key to successful integration is regulation, meaning that the nervous systems of humans and horses involved feel safe, settled, and relatively at ease. We want to start from a place of neutrality, which may mean first working with the horses to help them find this state. To do this, you must first find this state of responsiveness and settled presence within yourself, as co-regulation is a key element of helping your horses settle and feel safe.

For my new mare, I created a smaller temporary paddock to allow the horses to interact safely over a fence and for her to be able to take space as needed. It took about two days to find neutrality where the horses could eat next to each other, were connecting calmly, and were aligning their spines in the same direction (a sign of attunement and a clear signal that we are getting ready to move to the next step of integration). Remember, some stress is inevitable and that’s okay as it’s a big change. What we want to limit is distress, where stress levels become harmful.

Creating a space that is safe for integration is important. Blocking off any corners where a horse might become trapped, closing stalls, and generally preparing the space well will reduce stress. I prefer a fair amount of room so horses can take space, but not enough to encourage them to gallop as we want them to stay in a regulated state as much as possible. Fencing must be safe, and all horses should be unshod or wearing front shoes only. Several water and forage stations should be available, with forage offered in hay nets, hay piles, or as grass. Scarcity of food and water resources can be one of the main reasons horses become dysregulated or aggressive during introductions. Plan to have forage available 24/7 during integration to prevent the horses feeling protective of resources; this may mean a change in your feeding plan.

Related: Stallion Housing Affects Welfare

To promote neutrality and calmness, start your introductions with one horse. If you have a larger herd to introduce, start your integrations with the most socially skilled horse. If you are introducing a horse that is less skilled or unsure, this allows them to learn from their new friend, and allows you to see how the new horse handles interaction and what you need to watch for with other herd members.

Learning to read horse behaviour and body language becomes key as you watch and monitor these interactions. Notice signs of stress (running, biting, kicking, shutting down), calming signals (going to eat, turning head away), and signs of attunement (alignment of spines). Educate yourself about what you are seeing and the differences between normal behaviour, hormonal behaviour, and escalating stress behaviour. This lets you allow the horses to work things out without panicking, and you can step in or shift the energy when things are escalating in unhealthy ways. You can also train yourself to stay calm even when it seems scary or intense. I remind myself to notice my breathing and notice my feet on the ground to help me settle during an integration.

Related: Equestrianism and Animal Rights

Slow things down. For many horses, it can be very supportive to do integrations in smaller doses so they don’t go past their threshold and they become very stressed or tired. This may mean monitoring their time together daily for several days, and then the new horse goes back to their own paddock to decompress until you feel their dynamic is settled and safe for all. It may also mean taking your horses together for a walk around the property to get them used to moving through the space together in harmony. Small steps pay off in the long run, with more settled bonds and a happier herd.

I always try to keep the goal top-of-mind with herd integrations — a happy, enriching herd life. It can feel like a daunting process but leads to great things in the long run. Visualize the good things, the mutual grooming, play, and napping together, and do your best to release your worry and fear around what could happen. It’s a journey, but the destination is absolutely worth it.

I wish you the very best on your upcoming herd integrations. If you want more information on this as well as how to create your own enriching and species-specific horse space, check out my new website Outside the Box Equine.

Related: The Code of Practice for the Care and Handling of Equines

Related: Good Fences Make Safer Horses

Main Photo: Shutterstock/Vera Zinkova