By Hans Wiza

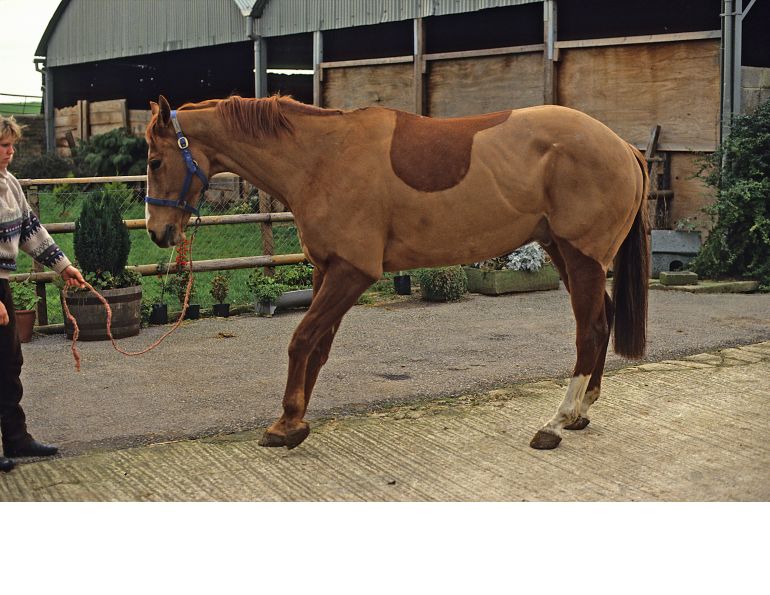

Sophie is a twelve-year-old seven-eighths Hanoverian mare whose main job is dressage. She is also hacked out for an hour or two a couple of times a week. She is fit and robust, but she has recurring bouts of problems with her stifles. Immediately after being shod, she has no issues. But as she gets further along in her shoeing interval her rider notices that her stifles keep catching.

This problem presents itself in several ways. At first, Sophie has an irregular hind step. It feels as if the leg is not coming fully underneath her to complete the stride in the supportive phase. As the shoeing interval progresses, the stifle will occasionally hook and catch. It’s not quite a stumble step but it feels as though the leg gives out, especially on corners and tighter circles. The afflicted leg loses its ability to bend the hock. It does not come forward properly and instead just punches the ground, which throws the hip into the air and can almost unseat the rider.

This has been going on for a couple of years. The vet has given injections with some moderate relief but no cure. At one point, Sophie had a wedged heel prescribed, but to no avail. Contrary to the popular dogma, raising the heels simply does not work for Sophie, nor does it work for most horses with this problem.

Sophie does better when she is freshly trimmed and shod with a flat shoe incorporating a tiny cork to prevent slipping on the grass and interlocking brick in the stable area.

The underlying cause is that the ligaments which hold the stifle joint have become stretched and frayed, and do not run along the joint smoothly. Raising the heels puts the fetlock joint behind the hoof and causes the pastern axis to drop. This lengthens the distance that the tendons must cover and subsequently stretches them. As the shoeing interval progresses, the fetlock gets further behind the hoof and this exaggerates the problem.

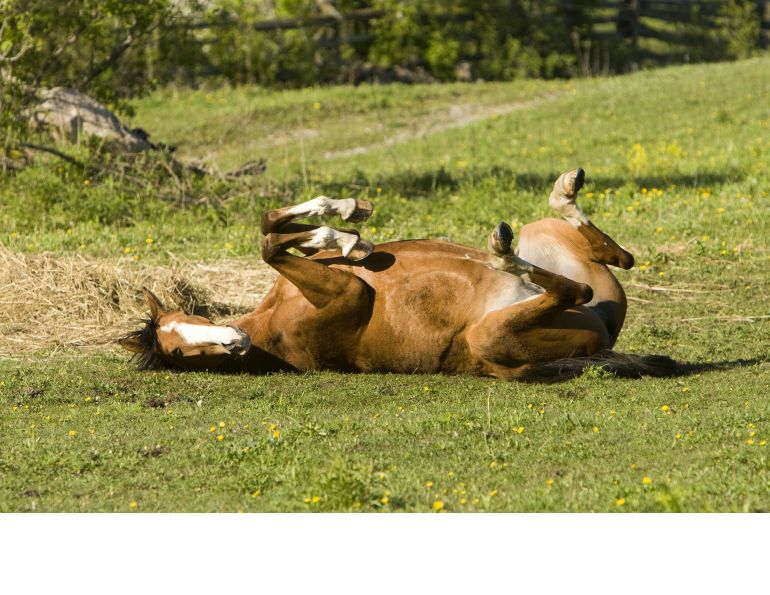

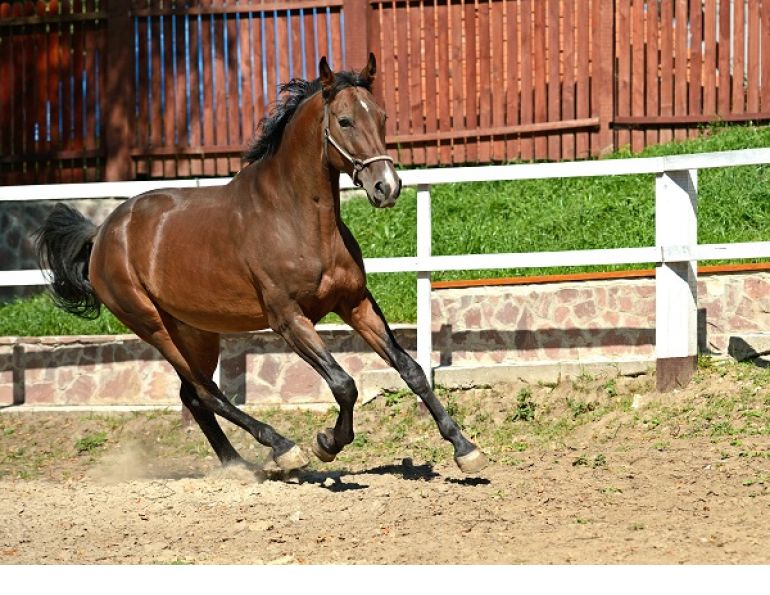

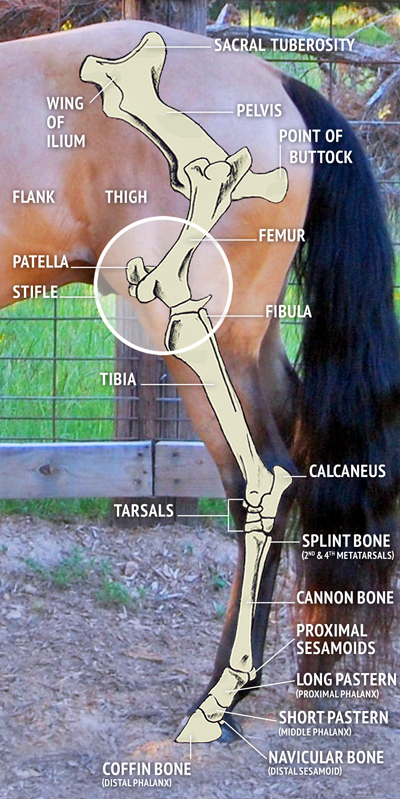

Comparable to the human knee, the stifle is a hinge joint at the end of the thigh, which provides flexion and extension of the hind limb. The stifle also participates in the passive stay apparatus, which locks the joint to maintain a straight, weight-bearing hind limb, allowing the horse to sleep standing up. Photo: Mary B/Flickr

The author is pointing to a spot that is generally recognized by both horse owners and chiropractors as becoming sensitive when stifle issues present themselves. Many riders say an invigorating massage both before and after riding makes their horses feel more comfortable. Photo courtesy of Hans Wiza

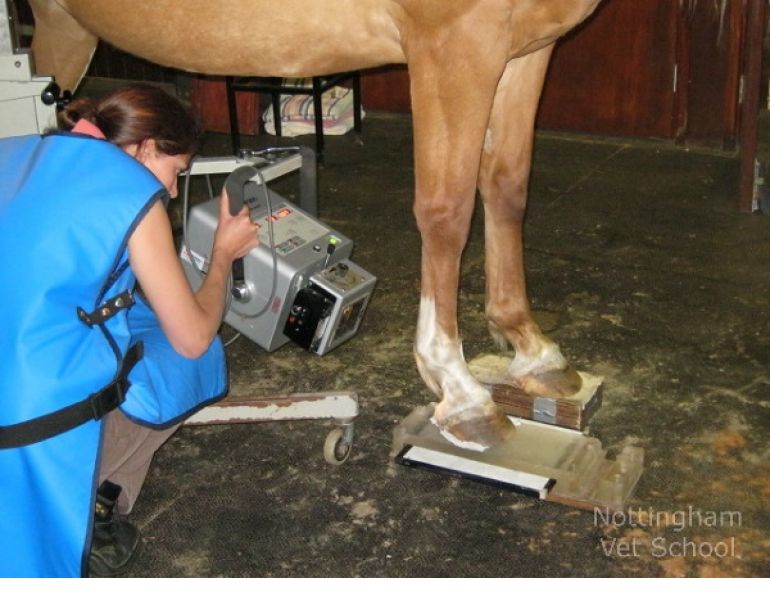

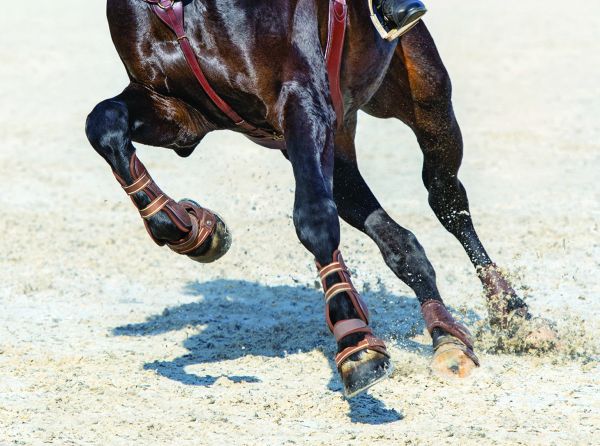

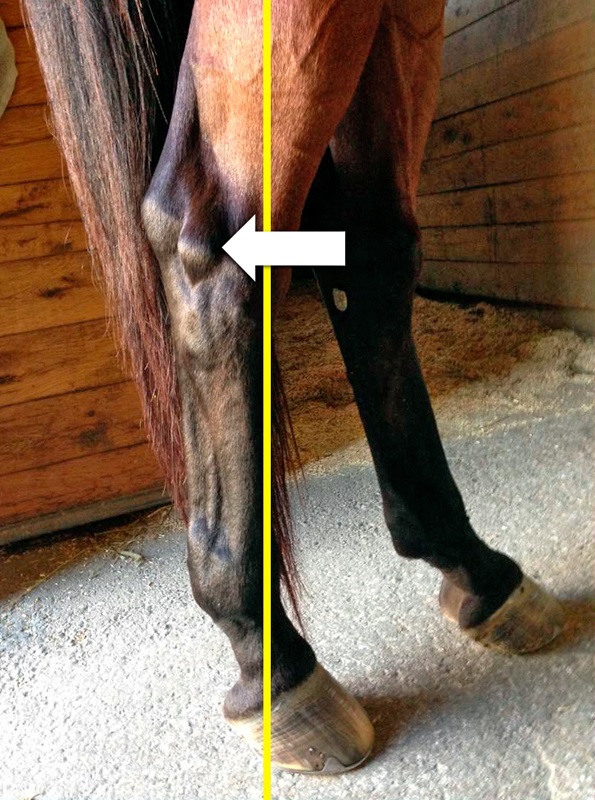

Even with the leg well back in the stance there is little hoof in the supportive phase. This will lead to hooking and dragging the toe. The arrow points to a thoroughpin, which is not uncommon for horses with stifle weakness. Photo courtesy of Hans Wiza

The solution

The shortest distance between two points is a straight line. With this in mind, it is absolutely mandatory that the heels be trimmed back to the widest point of the frog. The toe must be shortened and the quarters must also be brought down to the same plane as the sole.

A horseshoe well set back at the toe decreases the reach in the forward aspect of the stride length, thereby preventing toe dragging. This keeps the distal strike point back closer to the centre of the hoof, which allows the fetlock joint to be positioned over the top of the hoof sooner. This in turn keeps the hoof joint aligned with the frontal vertical edge of the cannon bone. And this enables the hoof to leave the ground as soon as the power is transferred to it with no delay caused by the fetlock needing to pass over the hoof in order to lift the heel off the ground. There should be no dip in the fetlock when the horse loads its foot. If there is a dip in the pastern when the horse loads it, the load will automatically be transferred onto the stay apparatus.

The toe of the hoof is now well behind the point of the stifle. This enables the leg to come forward without hollowing the back. Photo courtesy of Hans Wiza

The newly shod hoof is now under the cannon bone. This causes the stay apparatus to be in equilibrium and thus reduces the tension on all connective tissue. Photo courtesy of Hans Wiza

The ligaments and tendons surrounding the stifle are part of this unique structure which, when locked, allows the horse to sleep standing up. If the stay apparatus is unduly loaded, this will increase the tension in the connective tissue resulting in the dreaded “hitch in the giddy up.”

We have observed that Sophie starts to get a little discombobulated around the middle of her fourth week and that a shoeing interval of no longer than five weeks keeps Sophie happy.

I recommend that riders keep a day book to track their horse’s changes, and use these records to plan an appropriate shoeing schedule with their farrier.

We change what we can and manage what we can’t change.

Main Photo Courtesy of Hans Wiza