The Horse's Impact on the West

By Todd Kristensen and Jack Brink - Department of Anthropology, University of Alberta

In the 1720s, horses made their long-awaited return to Alberta's vast prairies, marking an extraordinary homecoming. It had been about 10,000 years since the province's expansive grasslands echoed with the sound of equine hooves. Fossil evidence reveals that North America was the original birthplace of the horse, with the species first appearing millions of years ago. While other animals, such as bison and mammoths, migrated into North America from Siberia, the horse followed a different path, eventually being domesticated by the horse-riding cultures of the Central Asian Steppes. However, the ancient horse that once thrived across Canada mysteriously disappeared thousands of years ago.

Morning light on the beautiful hoodoos at Writing-on-Stone Provincial Park southeast of Lethbridge, Alberta. Photo: Reproduced with permission from Robert Berdan

The cause of the horse's extinction in Alberta remains a mystery, but archaeological findings suggest that horses played an important role for the province’s earliest human inhabitants. When horses returned to the region in the 1700s, they quickly surpassed their historical significance, becoming central to both Indigenous and European cultures on the western frontier. The story of the horse in Alberta is a captivating tale of resilience, adaptation, and cultural transformation.

Contrary to popular belief, Alberta was not just home to vast herds of bison. Horses once dominated the northern Great Plains. Palaeontological records around Edmonton indicate that before the last Ice Age (about 40,000 to 25,000 years ago), horses outnumbered bison by as much as ten to one. By 10,000 years ago, as many as six different species of now-extinct horses roamed the region. These ancient horses spent their days grazing on grasses and avoiding predators, such as cave bears, American lions, and the swift American cheetah. Perhaps the most significant threat to their survival, however, was an intelligent two-legged predator—early humans.

Related: Ya Ha Tinda, The Canadian Government's Only Working Horse Ranch

The Mexican horse ranged north into Alberta’s meadows where it was hunted by the province’s first humans. Residues of horse blood were found on ancient spear tips at a site not far from Fort Macleod in southern Alberta. Photo: Courtesy of the University of Alberta

When groups like the Blackfoot and Assiniboine mastered horseback riding, the horse changed just about every dimension of life on the plains. Photo: Painting by George Catlin, reproduced with permission from the Bruce Peel Special Collections Library, University of Alberta

This map shows the chronological spread of the domestic horse into Alberta over the last 500 years. Photo: Courtesy of the University of Alberta

A rocky canvas of ancient art at Writing-on-Stone Provincial Park depicts a domestic horse in a buffalo hunt. Photo: Courtesy of the University of Alberta

This combat scene from Writing-on-Stone shows an early horse draped with body armour. Photo: Reproduced with permission from Michal Klassen

Despite its common name, the Mexican horse (Equus conversidens) ventured well north into Alberta’s tundra meadows and onto the menu of Alberta’s first humans. Recent archaeology work reveals that people hunted the Mexican horse at a site not far from Fort Macleod in southern Alberta. Ancient residues of horse blood were found on stone spear tips used over 10,000 years ago. Fossil horse bones have also been found near Grande Prairie, Taber, Cochrane, and in several Edmonton-area gravel pits. The first humans to ever set foot in the province followed footsteps of the Mexican horse and they likely ambushed these animals at watering holes or along trails, while some hunters may have corralled horses onto mud flats that hindered their escape. But around 10 millennia ago, the horse disappeared from the entire continent.

When the horse returned with the Spanish 500 years ago, Indigenous peoples had a more profound place for the equestrian animal than the dinner table. Once groups like the Blackfoot and Assiniboine mastered horseback riding, the horse occupied and changed just about every dimension of life on the plains. The new hooved pets created new hunting strategies. They changed the way people moved across the prairies, altered the dynamics of plains warfare, and by the 1800s Indigenous Plains people such as Post Oak Jim (a member of the Comanche) could safely claim that “Some men loved their horses more than they loved their wives.”

Reconstructing when and how the domestic horse spread into Alberta has been tricky. Historic records offer only a handful of references to the timing and motivation of horse adoption by Indigenous people during those early days in the 1700s. The journals of the great explorer and fur trader David Thompson provide one extraordinary glimpse. Thompson spent the winter of 1787-1788 camped with the Peigan (Piikani) in Alberta’s foothills where he shared a tipi with an elderly Cree man, Saukamapee. Saukamapee had been raised by the Blackfoot and while winter’s wicked winds ruffled the tipi hides, he regaled Thompson with the history and lore of his adopted people, including the first ever horse sighting.

The Peigan had been raided by dreaded rivals who rode animals “swift as the deer.” Equally swift was the spread of this news of a new beast. The first chance to see a horse up close came when the Peigan attacked a horseback rider. The man got away but the horse was killed with an arrow. “Numbers of us went to see him,” Saukamapee recounted, “and we all admired him; he put us in mind of a stag [elk] that had lost his horns; and we did not know what name to give him. But as he was slave to man, like the dog, which carried our things, he was named Big Dog.”

Related: Dogs and Horses - Man's Best Friends

Related: Reviving Ancient Horse Riding Skills

In addition to the few written records, there is a unique piece of heritage that offers fleeting (and beautiful) glimpses of how the horse changed the west. Writing-on-Stone Provincial Park, which is nestled into the winding valleys and coulees of the Milk River in southern Alberta, houses one of the largest collections of rock art in North America. For over a thousand years Indigenous people have been carving and painting their stories on the sandstone hoodoos and massive canyon walls. Appropriately named, Writing-on-Stone is a rocky canvas of ancient art that spans many centuries, and the horse looms large in those depictions.

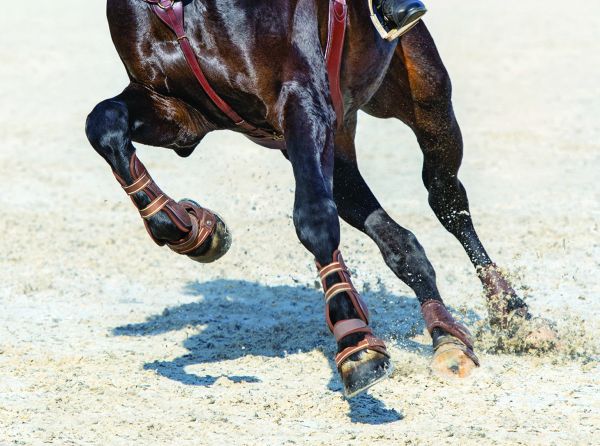

Horse carvings depict a wide variety of events and beliefs including battle scenes, hunting expeditions, tallies of horses acquired through trading or raiding, and commemorations of a powerful, respected animal. In everyday life, the horse had several different uses. Some horses were destined to replace the dog as beasts of burden that carried belongings such as tipi poles and skins during long marches from camp to camp. Other horses were highly revered as “buffalo runners,” prized for being long-winded and intelligent when faced with the challenge of overcoming a buffalo weighing 1000 pounds or more.

Early Europeans remarked on the instincts and skill of the buffalo runners. These horses had learned to read the buffalo and knew when to dodge an oncoming charge even in the midst of the swirling dust and flowing blood of a buffalo chase. Moments before the buffalo run began, the Pawnee of the Central Plains were known to whisper terms of endearment into their horses’ ears. They called them brother, father and uncle, and encouraged them not to fear the buffalo but to run well. For buffalo hunters who needed both hands free for their weapons, a well-trained horse was essential to survival.

Other horses were used for small trips, training, or as gifts, and the artwork at Writing-on-Stone hints at these practices. The stony art also tells archaeologists how beliefs about the horse changed over time. For example, early carvings of horses at Writing-on-Stone show them draped with leather body armour; a trait borrowed from the Spanish. This was soon found to be too hot, heavy and impractical (as well as ineffective against musket balls and bullets). Later images of horses show them unadorned and in full flight. Both wild and captive horses multiplied dramatically and what was once a novel sight on the rolling grasslands became a necessity of life on the plains.

The horse quickly galloped into the social lives of indigenous cultures. Families that could acquire many horses gained prestige and respect. Festive gatherings that included thousands of horses were not uncommon, which placed great demands on local rangeland. The need for greener pastures determined where these events could be held and how often people were forced to move across the prairies. Horse raiding became a mark of courage for many groups and horses were traded for a multitude of things including European goods, food, membership into societies, and spiritual power. Esteemed leaders often lent horses to families in need, offered them as gifts associated with weddings, and were sometimes buried with horses that would escort them to the afterlife.

By the time the first Europeans began to arrive in Alberta in the mid- to late 1700s, horses were a hot commodity. Their introduction changed the way indigenous groups interacted with each other and with the new European fur traders. While slick beaver furs were motivating European economic interests in Alberta, horses, guns, and buffalo meat were becoming entwined in complex trade networks that would shape the history of the prairies.

Fur traders needed food that locals were willing to deliver if the price was right. Pounded pemmican (dried buffalo meat) fed the fur trade, and in exchange, indigenous traders acquired metal tools, clothes, and guns. Growing appetites in the 1800s led to a sharp drop in buffalo populations. The use of buffalo leather for clothes and machinery, combined with unregulated sport hunting, hastened the demise of an animal that once numbered in the millions. When the buffalo herds vanished, the hooves of the horse pounded on. Ranchers and farmers continued to rely on horses to break the land and they’ve occupied an important place in cowboy culture ever since. The use of modern horses continues to evolve to suit our recreational and economic needs.

The rare and unique collection of rock art at Writing-on-Stone is a provincial treasure that captures pivotal centuries of modern Plains cultures. For this reason, the area is a Provincial and National Historic Site. Writing-on-Stone always was, and still is, a sacred place to the Blackfoot people; a place where spirits dwell among the towering spires and sheer walls of sculpted bedrock. Visitors are encouraged to learn the story of this powerful place while immersing themselves in its stunning valleys and rolling uplands. History books often contain dry written records but one of the many benefits of the stony archive of art on the Milk River is that it can be enjoyed and appreciated under blue skies. What better way to learn how the horse changed the West than from reading the sandstone walls of Writing-on-Stone while cool breezes blow in hints of sage and a red-tailed hawk reads over your shoulder? Site protection combined with a healthy respect for Blackfoot traditions and the archaeological record will ensure that the history of the Old West will endure and the story of the horse will ride on.

Related: Skijordue: Riding and Sliding

Related: A Country Built by Horsepower

Main Photo: Brave and well-trained horses known as “buffalo runners” were prized by hunters who needed both hands free for their weapons, as this painting by George Catlin from the 1800s illustrates. Photo reproduced with permission from the Bruce Peel Special Collections Library, University of Alberta