By Eileen E. Fabian (Wheeler)

Horse fence can be one of the most attractive features of a horse facility. Fencing is a major capital investment that should be carefully planned before construction. It should keep horses on the property and keep away nuisances such as dogs and unwanted visitors. Fences aid facility management by allowing controlled grazing and segregating groups of horses according to sex, age, value, or use. But not all fence is suitable for horses.

Well-constructed and maintained fences enhance the aesthetics and value of a stable facility, which in turn complements marketing efforts. Poorly planned, haphazard, unsafe, or unmaintained fences will detract from a facility’s value and reflect poor management. Good fences can be formal or informal in appearance, yet all should be well built and carefully planned. Many experienced horse owners will relay stories about the savings for cheaper, but unsafe, horse fence (barbed wire, for example) eventually being paid for in veterinary bills to treat injured horses.

Often, more than one kind of fence is used at a facility. Different fences might be installed for grazing pastures, exercise paddocks, riding areas, or for securing property lines. Land topography influences the look, effectiveness, and installation of fencing. Consider different horse groups. Stallions, weanlings, mares, mares with foals, and geldings all have different fencing requirements.

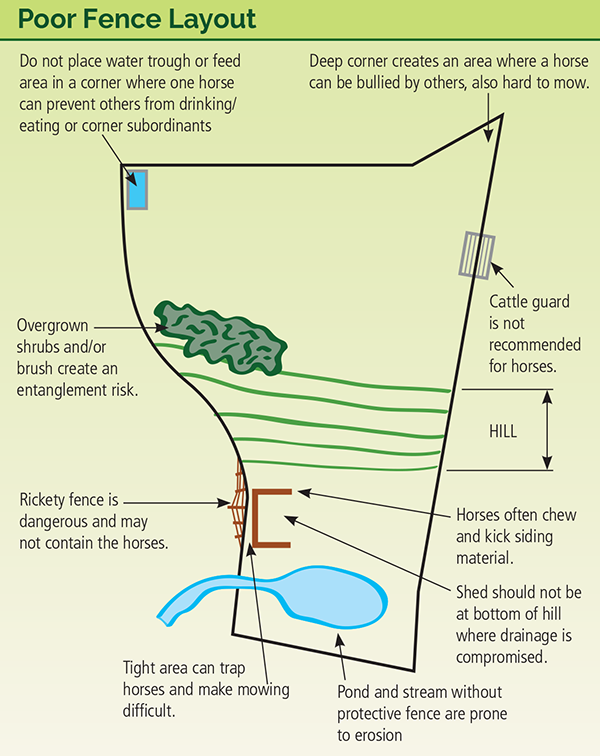

Pasture use may range from exercise paddocks (corrals) to grazing or hay production. Paddock layout should allow for ease of management, including movement of horses, removal of manure, and care of the footing surface. Pasture design should allow field equipment, such as mowers, manure spreaders, and baling equipment, to enter and maneuver easily. This will reduce fence damage by machinery and the time needed to work in the field.

This article presents information useful in planning fences for horse facilities. The emphasis is on sturdy, safe horse fence typically used in Canada.

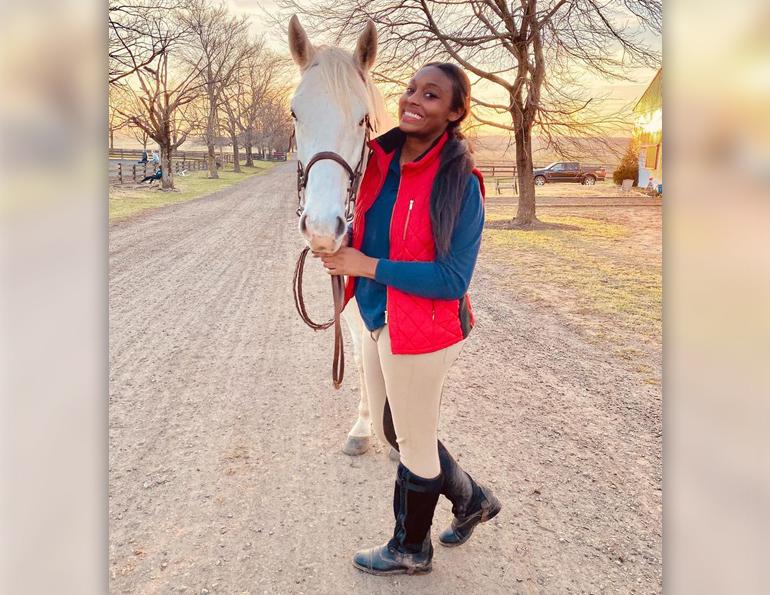

Mares with foals have specific fencing requirements from those for stallions, geldings, and young stock. When creating paddocks for mares and foals, position the bottom rail no higher than 30 cm to prevent foals from rolling under the fence. Photo: ©Thinkstockphoto/Kent Weakley

The Best Fence

Understand the purpose of a fence. The true test of a fence’s worth is not when horses are peacefully grazing, but when an excited horse contacts the fence in an attempt to escape or because he never saw it during a playful romp. How will the fence and horse hold up under these conditions? A horse’s natural instinct to flee from perceived danger has an effect on fence design. Like other livestock, horses will bolt suddenly, but since they are larger and faster, they hit the fence with more force. Also, horses fight harder than other livestock to free themselves when trapped in a fence. There are many types of effective horse fencing, but there is no “best” fence. Each fencing type has inherent trade-offs in its features.

A “perfect” fence should be highly visible to horses. Horses are farsighted and look to the horizon as they scan their environment for danger. Therefore, even when fencing is relatively close, it needs to be substantial enough to be visible. A fence should be secure enough to contain a horse that runs into it without causing injury or fence damage. A perfect fence should have some “give” to it to minimize injury upon impact. It should be high enough to discourage jumping and solid enough to discourage testing its strength. It should have no openings that could trap a head or hoof. The perfect fence should not have sharp edges or projections that can injure a horse that is leaning, scratching, or falling into it. It should be inexpensive to install, easy to maintain, and last 20 years or more. And finally, it should look appealing.

Unfortunately, no type of fence fits all the criteria for the perfect fence. Often there is a place for more than one type of fence on a horse facility. Stable management objectives and price ultimately determine which fencing is chosen. Many new fence materials and hybrids of traditional and new materials are now available.

Features That Apply to Any Fence Type

Good Planning Attributes

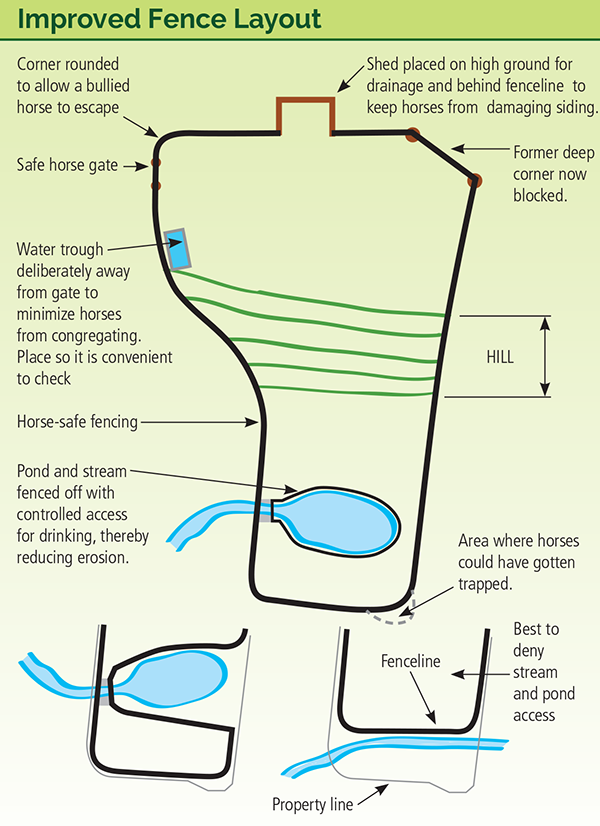

Planning includes more than selecting a fence type. It is best to develop an overall plan where the aesthetics, chore efficiency, management practices, safety, and finances are considered. The best planning involves a layout drawn to scale that shows proposed gates, fence lines, where fences cross streams or other obstacles, irregular paths along a stream or obstacle, traffic routes for horses and handlers, routes for supplies and water, vehicle traffic routes, and access for mowing equipment. All these should be in relation to buildings and other farmstead features.

Select and install fencing that allows easy access to pastures and does not limit performance of stable chores. Gates should be easy to operate with only one hand so the other hand is free. Fencing should also allow easy movement of groups of horses from pasture to housing facilities. All-weather lanes should connect turnout areas to the stable. Lanes can be grassed or graveled depending on the type and amount of traffic that uses them. Make sure they are wide enough to allow passage of mowing equipment and vehicles. Vehicles such as cars, light trucks, and tractors can be up to eight feet wide. Farm equipment needs lane widths of 12 to 16 feet (3.6 to 4.9 m) to comfortably negotiate. Narrower lane widths are acceptable for smaller tractors or mowing equipment. Remember to leave room for snow storage or removal along the sides of lanes and roads.

It is best to eliminate fence corners and dead end areas when enclosing a pasture for more than one horse. By curving the corners, it is less likely that a dominant horse will trap a subordinate. Round corners are especially important for board fences and highly recommended for wire fences.

Most wire fencing is installed with the wire under tension as part of the design strength of the fence. This tension may be modest, just enough to keep the wire straight and evenly spaced throughout seasonal temperature changes in wire length, or may be quite substantial, as with high-tensile wire fence. With tensioned fencing, rounded corners may not be as strong or durable as square ones. A slight outward tilt of support posts on curved corners can help resist the inward forces of the tensioned wire. Position the tensioned wire on the outside of the fence post as it travels around the curve, then back to the inside (horse side) on the straight sections. It is possible to build square corners for tension fences and use boards to prevent horses from getting into the corner. This creates areas that limit grazing, requiring regular mowing, but it is cheaper to construct than curved corners.

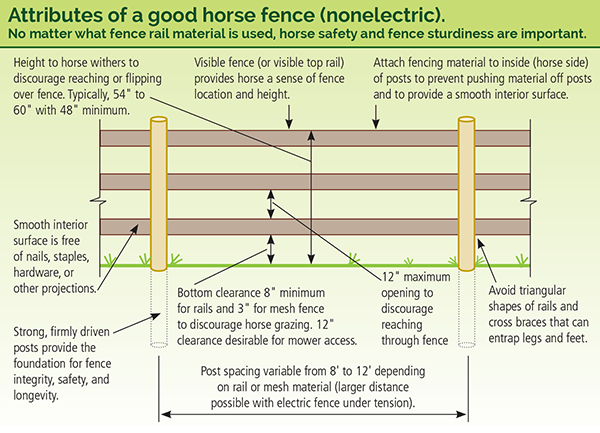

Good Fence Attributes

Horse fences should be 54 to 60 inches (1.37 to 1.52 m) above ground level. A good rule for paddocks and pastures is to have the top of the fence at wither height to ensure that horses will not flip over the fence. Larger horses, stallions, or those adept at jumping may require even taller fences. At the bottom, an 8-inch (20 cm) clearance will leave enough room to avoid trapping a hoof, yet will discourage a horse from reaching under the fence for grass. A bottom rail with clearance no higher than 12 inches (30 cm) will prevent foals from rolling under the fence. Fence clearance varies with fence types. Higher clearances allow small animals, such as dogs, to enter the pasture. Fences should be built with particular attention to fence post integrity. Several fence material manufacturers provide good detailed guides to assist in construction and material selection.

Fence openings should be either large enough to offer little chance of foot, leg, and head entrapment, or so small that hooves cannot get through. Small, safe openings are less than 3-inches (7.6 cm) square, but can depend on the size of the horse. Tension fences, such as the types that use high-tensile wires, usually have diagonal cross-bracing on corner assemblies. These diagonal wires or wood bracing provide triangular spaces for foot and head entrapment. Good fence design denies horse access to the braced area or at least minimizes hazards if entrapment occurs.

Horses will test fence strength deliberately and casually. Horses often reach through or over fences for attractions on the other side, thus, sturdy fences are essential. Fences that do not allow this behaviour are the safest. Keep open space between rails or strands to l2 inches (30 cm) or less. For electric fences, this open distance may be increased to 18 inches (45 cm) since horses avoid touching the fence. With most fence, and particularly with paddock and perimeter fence, a single strand of electric wire can be run 4 to 6 inches (10 to 15 cm) above or just inside the top rail to discourage horses who habitually lean, scratch, or reach over fences.

The fence should be smooth on the horse side to prevent injury. Fasten rails and wire mesh to the inside (horse side) of the posts. This also strengthens the fence. If a horse leans on the fence, its weight will not push out the fasteners. Nails and other fasteners should be smooth without jagged parts that can cut the horse or catch a halter.

Visible fences will prevent playful horses from accidentally running into them. A frightened horse may still hit a visible fence while he is blinded with fear. A forgiving fence that contains the horse without injury is better than an unyielding brick wall. Wire fences are the least visible, so boards or strips of material are often added.

Fence Post Selection

The fence post is the foundation of the fence, so its importance cannot be overemphasized. The common element in virtually all successful horse fences is a wooden post. Setting posts represents the hardest work and the most time-consuming part of fence building, and is absolutely the most critical to the long-term success of the fence.

Driven posts are more rigid and therefore recommended over handset posts or those set in predrilled holes. Driven posts are pounded into the ground through a combination of weight and impact by specialized equipment. The principle behind driven posts that makes them so secure is that the displaced soil is highly compacted around the post, resisting post movement. Even for do-it-yourself projects, you should contract the job of driving posts. Post-driver equipment is nearly impossible to rent due to liability concerns. Under some dry, hard, or rocky soil conditions, a small-bore hole will be necessary for driven posts.

Wood is recommended for all horse fence posts. The best buy is a pressure-treated post from a reputable dealer. The preservative must be properly applied to be fully effective. Initially, treated posts are more expensive than untreated ones, but they last four times as long as untreated ones. Depending on soil conditions and preservative treatment quality, a pressure-treated post can last 10 to 25 years.

Suitable wooden fence posts are similar for board and mesh fences. High-tensile wire and other strand-type fences require similar posts, but distances between posts are much longer than for board or mesh fence. Post distance on high-tensile wire fence depends on wind influences and topography. Round wood posts are stronger and accept more uniform pressure treatment than square posts of similar dimension. Attachment of wooden rail boards to round wood posts is improved when one face of the post is flat.

Photo: ©Suyerry/Dreamstime.com

Exceptions to wood posts are allowed for horse-safe steel posts typically used on chain link fences, pipe posts from welded fences, and rigid PVC fence post. Hollow posts require top caps to cover the ragged top edge, or should be designed so that the top fence rail covers the top of the post. Recycled plastic, 4-inch (10 cm) diameter solid posts are suitable for horse fence, but require a small-bore pilot hole before driving. Metal and fiberglass T-posts are slightly cheaper but pose a serious risk of impalement and are not recommended. They are also not strong enough to withstand horse impact without bending. With a plastic safety cap installed on the top, T-posts may be cautiously used in very large pastures where horse contact is rare.

How deep to set the post for structural stability varies considerably with soil conditions. Soil characteristics play a major role in determining the longevity and maintenance requirements of a fence. Some soils remain wet and can quickly rot untreated wooden posts. Posts in sandy or chronically wet soil will need to be set deeper and perhaps supported by a collar of concrete casing. Other soils tend to heave with frost and can loosen posts that are not driven deep enough. Fences under tension, such as wire strand or mesh materials, will require deeply set posts to offer long-term resistance against tension. A typical line post depth is 36 inches (.9 m). Corner and gateposts are required to handle greater loads and are about 25 percent larger in diameter and should be set deeper, often to 48 inches (1.2 m).

Gates

Gate Design

Gates should have the same strength and safety as the fence. Gates can be bought or built in as many styles as fencing, but do not have to be the same style as the fence. The most common and recommended materials are wood and metal tubes. Easy-to-assemble kits for wooden gates with all the hardware, including fasteners, braces, hinges, and latches, can be bought from farm, lumber, or hardware stores. Horse-safe tubular pipe steel gates (often 1 3/8-inch or 3.5 cm outer diameter pipes) have smooth corners and securely welded cross-pipes to minimize sharp-edged places for cuts and snags. By contrast, channel steel or aluminum stock livestock gates are not recommended for horse use due to their less-sturdy construction and numerous sharp edges.

Avoid gates with diagonal cross-bracing. Although this strengthens the gate, the narrow angles can trap legs, feet, and possibly heads. Cable-supported gates offer a similar hazard to horses congregating around the gate. If gate supports are needed, a wooden block called a short post can be placed under the free hanging end of the gate to help support its weight and extend hardware life. The use of a cattle guard (rails set over a ditch) instead of a gate is not recommended since horses do not consistently respect them. Horses have been known to jump them or try to walk over them, which results in tangled and broken legs.

Rounded fence corners prevent horses from becoming trapped by aggressive herd-mates. Gates should be as tall as the fence, and positioned toward the middle of the fence line. Photo: ©Cbanck/Flickr

Gates should be as tall as the fence to discourage horses from reaching over or attempting to jump over the gate. Gates can be up to 16-feet (4.9 m) wide, with a minimum of 12 feet (3.6 m) wide, to allow easy passage of vehicles and tractors. Horse and handler gates should be no less than 4 feet (1.2 m) wide, with 5 (1.5 m) feet preferred. Human-only passages are useful for chore time efficiency.

Fencing near gates needs to withstand the pressures of horses congregating around the gate, which means it needs to be sturdy, highly visible, and safe from trapping horse feet and heads. Some paddock gates are positioned to swing into the pressure of the horse to prevent horses from pushing the gate open and breaking latches. On the other hand, gates that are capable of swinging both into and out of the enclosure are helpful when moving horses. Additional latches are recommended to secure the gate in an open position, fully swung against the fence, not projecting into the enclosure.

Gates are hung to swing freely and not sag over time. The post holding the swinging gate maintains this free-swinging action, necessitating a deeply set post with a larger diameter than fence line posts. Gate hardware must withstand the challenges of leaning horses and years of use. A person should be able to unlock, swing open, shut, and lock a properly designed gate with only one hand so that the other hand is free to lead a horse or carry a bucket, for example.

Gate Location

In most horse operations, gates are positioned toward the middle of a fence line where horses are individually moved in and out of the enclosure. This positioning eliminates trapping horses in a corner near a gate. On operations where groups of horses are herded more often than individually led, gates positioned at corners will assist in driving horses along the fence line and out of the enclosure. Place pasture gates opposite each other across an alley. Gates that open to create a fenced chute between the two pastures will aid horse movement.

Fencing along driveways and roads has to provide room to maneuver vehicles to access gates. Entry driveway surfaces are often 16 feet (4.9 m) wide with at least 7 feet (2 m) on each side for snow removal, snow storage, and clearance for large vehicles. Remember that when driving through a gate while towing equipment, substantial room may be needed to turn between fence lines. A tractor towing a manure spreader or hay wagon will use 16 to 25 feet (4.9 to 7.6 m) to make a 90-degree turn. The easiest option is to position gates so that machinery can drive straight through the gate. Position gates where good visibility along a road will provide safety for slowly moving horse trailers and farm equipment that are entering and exiting the road. Place gates 40 to 60 feet (12 to 18 m) from a road to allow parking off the road while opening the gate.

Summary

The most time-intensive part of fence building takes place before any ground is broken. Thoughtful fence planning and layout will help make daily chores and routines more efficient. The best fence differs from facility to facility and even within a horse property; different fence types are used to meet the objectives of the enclosure. Good fence design emphasizes a proper foundation, or post integrity. By taking the time to understand a facility’s fencing needs and expectations, you can provide a safe, functional fence that will provide years of service and enhance the property’s value.

This article is reprinted with kind permission from Pennsylvania State University.

This article was originally published in the May 2015.

Main Photo: ©Thinkstockphoto/Danielle Mussman