What are the Differences?

By Jochen Schleese, CMS, CSFT, CSE

When mankind began riding horses, and saddles were developed to help keep riders astride their mounts, the original purpose of the saddle was to support the horse in his job. Saddles were designed to accommodate the demands placed on horses during activities such as combat, transportation, and sport. And since riding in long skirts was not practical and it was unbecoming for a women to straddle a horse, side-saddles were created to allow women to ride. Recent years have seen changes in saddles from mainly functional to often fashionable (featuring bling, silver, etc.). More recently, as the general demographic of riders changed to primarily women, gender considerations have been incorporated into the mix of saddle design for both English and Western disciplines.

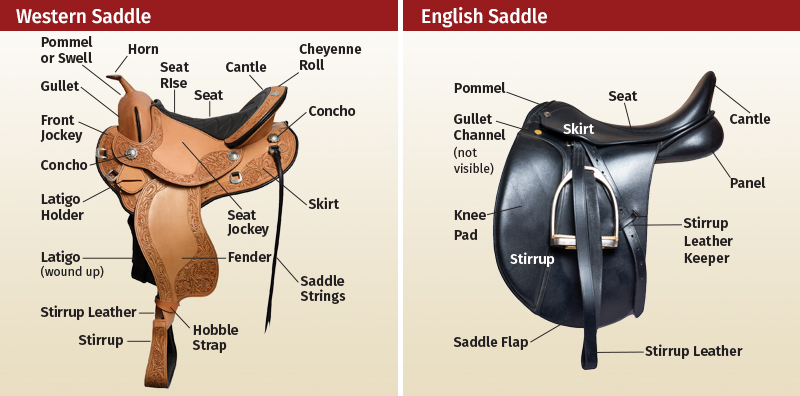

Western Saddles

In Western disciplines, riders have been willing to spend quite a bit of money to get the right look, with fashionable saddles incorporating beautiful tooling and silver accoutrements. The basic design or style of the saddle can include many variations in the seat, fork, swell, horn, cantle, and skirts, depending on the specific discipline it is designed for. All of these can change with the discipline. Western saddles are categorized by fork style, intended use, tree type, breed type, material type, and production technique. Let’s look at some of the more popular types of Western saddles by intended use.

Cutting saddles are designed for riders who will separate a single animal from the herd. The flat seat and wide swells help the rider stay centered. These are not overly secure saddles, but designed to keep the rider balanced and out of the horse’s way during starts, stops, and turns. They can also be used for penning and for training, even for reining if needed.

Related: Saddle Fit for the Rider - Male vs Female

Roping saddles are made for demanding use and maximum freedom of movement for the rider. These saddles must have a strong tree and horn, with a lower cantle for easier dismount. The seat is usually deep and covered in suede for grip.

For barrel racers, the saddle is designed for speed – the cantle is higher, the horn is thinner and longer (easier to hold on to), and the swell and cantle are built to wedge the rider into position so that when the rider comes out of the gate and has to make turns at full speed, she sits securely. Many saddles also feature wider gullets and greater flare on the bars to help the horse move freely, and with forward-hung stirrups to keep the rider in position by being able to brace the legs. Since females also comprise the majority of barrel racers, these saddles are often very flashy with bold colours and materials.

The barrel racing saddle is built for speed and security during tight turns. Photo: Shutterstock/Sergei Bachlakov

In reining saddles, the cantle and swell are lower and the seat is shaped to allow the rider to sit further back in the saddle to stay out of the horse’s way. A reining saddle provides the rider with the close contact needed to communicate subtle commands to the horse for the meticulous patterns of circles, spins, and sliding stops.

For the relatively newer sport of Western Dressage, the ground seat, the cantle, the swell, and skirts are designed to place the rider more forward and over the centre of balance on the horse’s back. The movement in this discipline is somewhat different from that in any other Western discipline. The horse’s head is ridden very low so that the back comes up – which means a different fit is required than that of a Western saddle in any other discipline.

Traditionally, Western saddles have focused more on fitting the rider, since only limited fitting to the horse could be done. The quarter bars, semi-quarter bars, or Arab bars were basically the only changeable options needed in the past. The horses used for Western disciplines were usually Quarter Horses, which were kept relatively pure in their breeding lines. Certain breeds were for certain jobs and there was less cross-breeding back then. Western saddle fitting is now more complicated since many more breeds are being ridden within the various disciplines.

Related: How to Tell if a Saddle Fits Correctly

The options for the rider in a Western saddle have also increased in recent years. For example, the bars can now be ordered with six different options, with innumerable variations in each combination of choices. These options include:

- Length of the bar;

- Twist of the bar (this is a different term than used for English saddles). The ribcage of a horse is angled more steeply near the shoulders than towards the back;

- Curvature of the bars (the “rock” in the tree bars);

- Width of the bars (mainly in the front);

- Flare of the bars (how much the bars flare up in front of the swell and behind the cantle); and

- Angle of the bar (mainly towards the front).

Schleese Saddlery has taken this individualization a step further and offers split bars and split ground seats to allow both male and female riders to use the same saddle, as well as fitting options to accommodate different horse conformations.

The cutting saddle is designed to keep the rider balanced and out of the horse’s way during cow work. Photo: Dreamstime/Vanessa Van Rensburg

English Saddles

English saddles have many more combinations of variables, some based on the same parameters as the Western saddle but with different nomenclature. These include saddle size, flap length and position, cantle height/seat depth, billet number and length, stirrup bar position and length, and gender accommodation, to name a few.

The general purpose saddle has become somewhat less popular in recent years as riders who are serious about the sport prefer the correct saddle for their particular discipline. Traditionally the GP came in two main variations – one more suitable for jumping, the other more suitable for dressage, and both were made to suit one of the following rider categories:

- An entry level rider uncertain as to which discipline to concentrate on;

- A recreational rider who was comfortable jumping occasionally but was usually “just riding out”; and

- The rider who wanted to buy just one saddle that could more or less do it all.

Eventing (cross-country) and jumping saddles are fitted differently yet again. There has to be enough room, especially at the front of the pommel at the withers and trapezius muscle, for both shoulders to move forward/backward/upward simultaneously in an explosion over the jump. Although the preference for these two sports seems to be close-contact saddles, many riders tend to place their saddles a little too far forward over and on the shoulder, which inhibits movement at the shoulder and creates the need for multiple pads to help bring the cantle back up to put the saddle in a level position. Where’s the close-contact now?

Related: Saddle Fit and Design for the Short Rider

The roping saddle features a sturdy horn and tree, and a lower cantle for easier dismount.

Endurance saddles are also fitted differently because endurance horses tend to be allowed to move in a natural way with their heads high to see where they’re going. When the head is high, the back is down, and the saddle needs to be fitted differently than for dressage where the head is lower and the back is up. The muscle definition in endurance horses compared to dressage horses is completely different as well, with as much disparity as between Thoroughbred racehorses and endurance horses. Just as human sprinters are typically bulkier than long distance runners, the same holds true for horses in comparable activities, and the saddle must accommodate these differences. Racing saddles are fitted differently again, as the jockey essentially does not sit in the saddle and is in the stirrups most of the time.

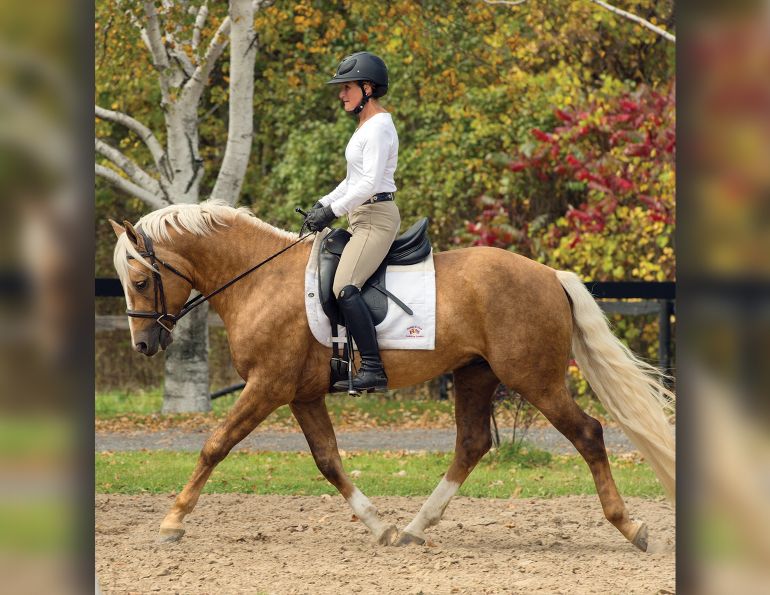

Classical dressage is usually ridden on baroque-style horses, but baroque saddles are fitted somewhat differently than general dressage saddles since, compared to modern dressage horses, the baroque horses use their muscles differently when they perform movements beyond piaffe, passage, and canter pirouette, such as the capriole, levade, and courbette.

A Baroque-type horse, ridden by Jane Savoie. Photo: Rhett Savoie

Dressage is the basis for all other disciplines – the word dressage means “training” in French – which is why the slightest differences in position and balance can affect performance. Just as ballet is recognized as the prerequisite for all dancers, every rider in every English discipline does (or should do) dressage. Technical training is difficult, but without good technique you won’t advance. And just like wearing proper shoes is essential in dance, proper saddle fit is extremely important, which is why it is mainly in dressage that saddle fit is regularly maintained. Dressage saddles are probably the most requested saddles for regular adjustments to achieve correct fit, and the maintenance of this fit is comparable to a race car’s pit stops – constant regular adjustment, maintenance, and tweaking may be required to ensure continued optimum performance of both horse and rider.

The main commonality between Western and English saddles, regardless of discipline, is that the saddle must distribute the weight of the rider and the saddle over a large weight-bearing surface (the panels) without putting undue pressure on very sensitive areas. The saddle needs to align the horizontal spine of the horse with the vertical spine of the rider to allow them both to move in complete harmony to accomplish whatever goal the rider has in their chosen discipline.

Related: Thoracic Assymetries and the Relationship with Saddle Fit

Main image: The reining saddle has a short horn, a flatter seat allowing the rider easier hip movement, and close contact skirts permitting better horse-rider communication. Photo: Shutterstock/Proma1