Equine Guelph

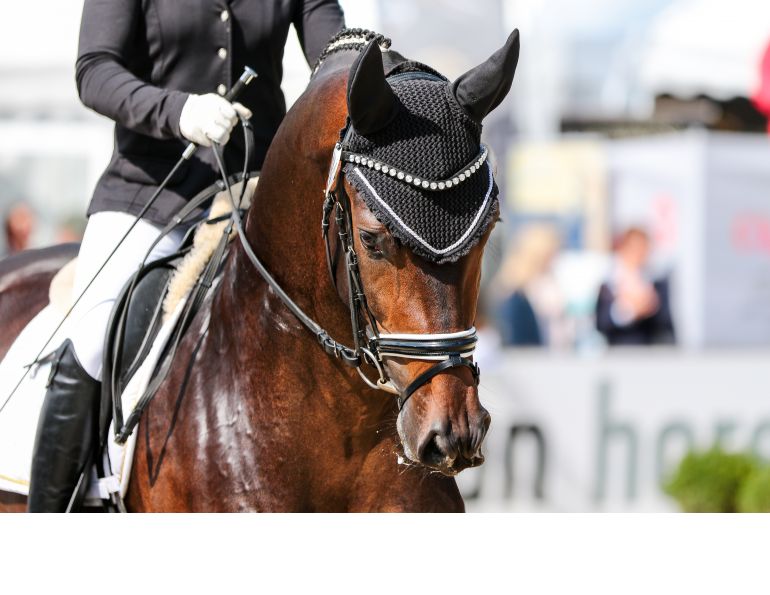

When horses talk, we listen. But how good are we at deciphering what they have to say? According to a study published in November 2021 by Dr. Katrina Merkies, researcher and associate professor at the University of Guelph, and her master student Haley Belliveau, we are faring well. The study is titled Human Ability to Determine Affective States in Domestic Horse Whinnies.

Using an online survey, participants categorized 32 equine whinny audio samples as positive and calm, or negative and excited. Knowing the difference and being able to act on this feedback could have positive equine welfare applications regarding how we interact with and manage horses.

In a video interview, Merkies discusses this interesting study and shares a couple of audio clips so you can test your skills in the language of horses.

“In today’s world, more and more emphasis is being put on animal welfare and the recognition of animals as sentient beings,” says Merkies. “As their caretakers, it’s our responsibility to provide the horses that we interact with a good quality of life, and to do this we must be able to understand how they function and what their needs are and what their desires are.”

Merkies went on to explain if we know from a horse’s vocalization that they are upset or fearful, then we can remove the stimulus or remove the horse from that situation. Likewise, if we know that a horse is happy, we can ensure repeat scenarios. Horses don’t have as large a vocal repertoire as many animals and as a prey species they are masters at communicating with body language.

The whinnies used in the study were collected from a variety of sources including Merkies’ past research on the weaning of foals, where distressed calls from both foals and mares had been captured. Other footage came from popular movies such as the beloved animated production, Spirit.

Around 65 percent of the time the survey respondents were able to tell whether a whinny happened during a positive or a negative situation. Not surprisingly, in a female dominated industry, almost 60 percent of the participants identified as female. Akin to past scientific studies on vocalizations in cats and pigs, women were more proficient at categorizing vocalizations than the men.

Age also presented a thought-provoking result, with more older people rating the horses’ whinnies as more highly aroused than did their younger counterparts. Merkies hypothesized, “Perhaps it’s because people who are older have more life experience and it may influence how they view the world. Maybe they’re more attuned to emotional content and vocalizations or it could simply be that hearing in older people has deteriorated and they were unable to discern the differences in the vocalizations, but that was one of our interesting findings.”

Horses use different vocalizations to communicate. They may whinny when reunited or separated from a friend; therefore, a whinny could be positive or negative depending on the situation. Merkies explains, “Different whinnies can communicate the size, sex, and social status of the caller. That whinny will tell them information, whether it’s a male or female horse, how large they are, probably whether they’re immature, young, or older.”

It would be interesting in future studies to find out how humans interpret more horse vocalizations like snorts, nickers, snores, and sneezes, and to examine what specific acoustic parameters humans use to categorize horse vocalizations. Merkies concludes: “Understanding the vocalizations that horses do use can help us understand their underlying emotional state and when we pay attention to those things, then we can work to make their life better.”

Photo: Shutterstock/Cindy Hughes