By Barbara Sheridan

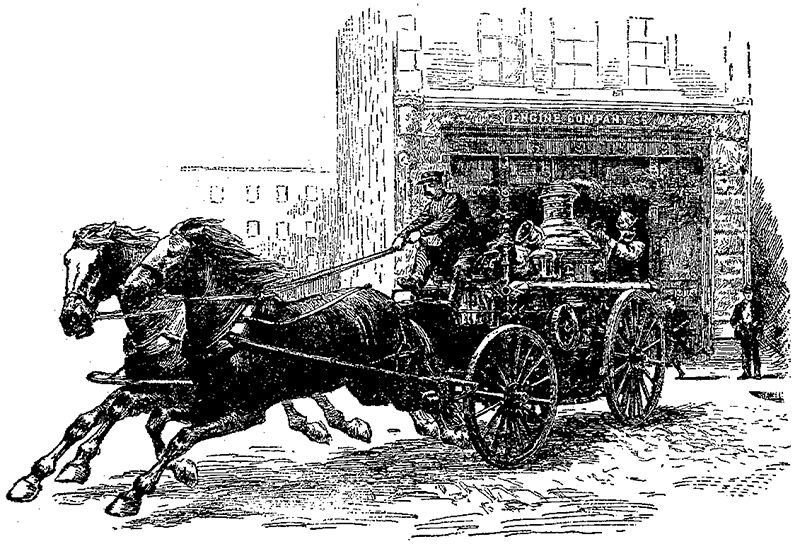

Nowadays, the blaring siren of a fire truck elicits a sense of awe and urgency as it races through the streets. People pause, marveling at the sleek, red machines with their chrome accents, while firefighters in dark uniforms hurry toward their mission. Yet, this image of modern firefighting is a far cry from the past, when cities depended not on engines of metal, but on the bravery and strength of fire-horses. In those days, citizens gathered in awe to witness the magnificent animals spring into action, playing a critical role in saving lives.

Beloved Toronto Mounted Police horse Brigadier died tragically in a hit-and-run in 2006, reminding us of the often-overlooked dangers that animals face in their service to the public. From the dedicated police canines to the horses of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP), animals have long been partners in ensuring the safety of Canadians. Among these unsung heroes were the fire-horses, who, with valor and heart, once played an integral role in the fire brigades. Though their era has passed, we must still honor the legacy of these courageous animals and their vital contributions to public safety.

The First Hoofbeats of Firefighting

Firefighting as an organized public service dates back to ancient civilizations, including the Roman Empire. However, it wasn’t until the mid-1800s that these efforts evolved beyond volunteer bucket brigades. As cities expanded, particularly across North America, the traditional method of passing water buckets became insufficient. Meanwhile, devastating fires ravaged major cities like Boston, Moscow, and London, proving that something more powerful was needed to combat the growing threat of fire. The need for innovation in firefighting technology grew ever more urgent, and it was in this environment that fire-horses would make their indelible mark.

As pumps began to replace bucket lines in the cause of firefighting, vehicles were designed to move the heavy apparatus more quickly to the sites of the fires. Originally teams of men, sometimes as many as ten or twelve, were used to pull the heavy pump carts; but as the equipment grew in size and power, the need for more pulling power increased. At first mules were used because they were more sure-footed on the dusty, unpaved roads. However, it was not long before horses replaced mules as the preferred weight-bearers. Horses were swifter and more easily trained and handled, and because of the newer cobblestones of most cities’ streets, the mules lost their advantage in footing.

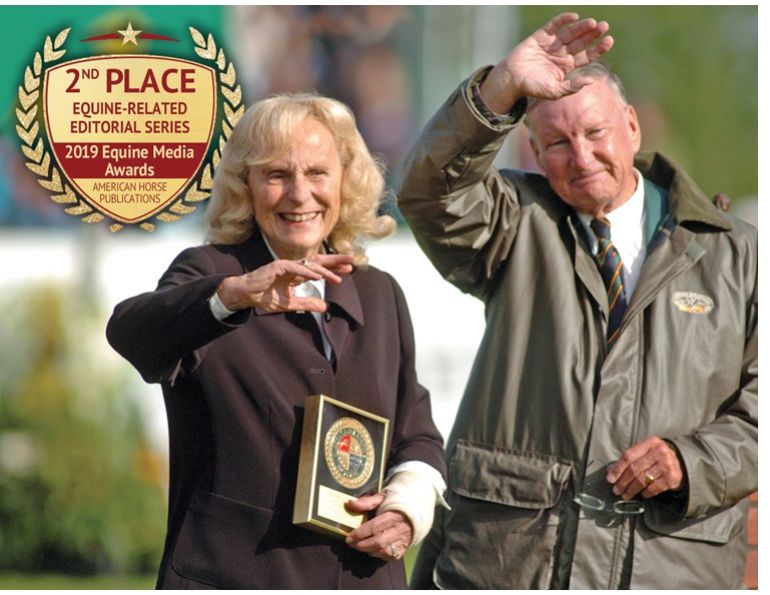

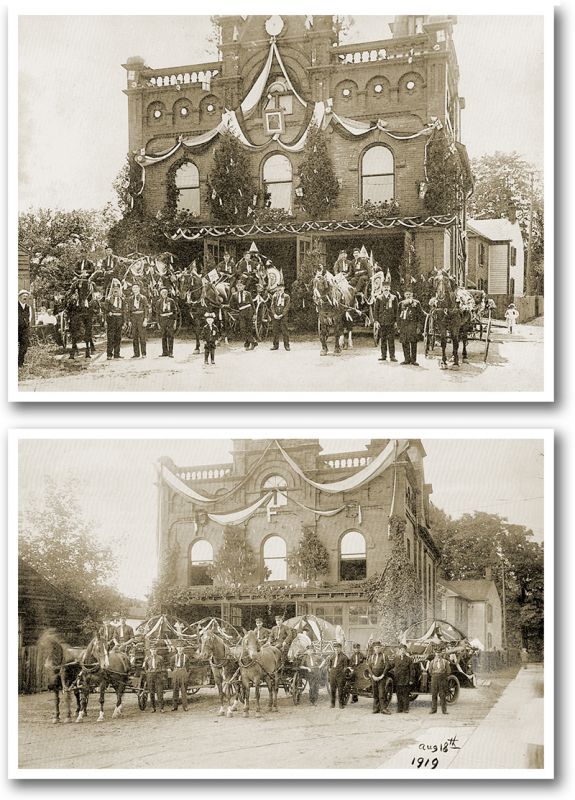

The Dundas Fire Department (Ontario) is pictured on proud display for a 1908 civic holiday and again in 1919 when it is evident that the horse-drawn fire wagons were being replaced by motor-driven vehicles. Photos courtesy of Dundas Fire Department

Fire Chief Knowles and Chief of Police Twiss of the Dundas, Ontario Fire Department heading south on Market Square at full speed, courtesy of firehorse Nell. Even after her retirement, Nell’s sense of duty called her back to the fire hall. One night, on hearing the fire bell, she broke away and galloped downtown to the door of the fire house.

According to Veronica Cosman, Assistant Curator of the Firefighters’ Museum of Nova Scotia located in Yarmouth, the use of fire-horses in that province started in the late 1800s, lasting only half a century. Nonetheless, many believe the fire-horse was the height of excitement in firefighting.

Related: Horses with Jobs: Logging Horses

“Watching them answer a general alarm fire provided an unforgettable sight,” Cosman says. “Heads tossing, tails flying, the horses’ hooves struck sparks from the uneven cobblestone as they pounded through the crowded streets with clouds of smoke following from the engines.”

Selecting a horse for a fire brigade was a difficult task. Usually, only one in a hundred horses proved to be acceptable. Besides the need to be highly trainable, the work also required great strength and stamina. Lightweight horses were typically used to pull hose wagons, while middleweights pulled “steamers,” the steam-powered pumpers. The largest horses, draft breeds weighing in at 1,700 pounds or more, pulled the heavy equipment, and hook-and-ladder carts. While the budgets of most fire brigades were modest, they spared little expense in acquiring the highest quality horses. Fast and reliable horses meant the difference between reaching a fire in time and getting there too late.

Colin Johnson, retired Fire Chief of the Dundas, Ontario Fire Department, and noted historian with a fondness for firefighting history, is author of the book, Dundas Fire Department Through the Years, 1833-1977, published by the Dundas Fire Department. Johnson says the horses used by the fire brigade were solid, placid creatures that were specifically trained to endure the clanging of bells and noise from the crowds commonly found at the scene of a fire.

“The fire-horses were level-headed and tough,” explains Johnson. “They needed the strength because as time went by those firefighting rigs got very heavy. So the real workhorse types, like Percherons, were preferred.”

Horses were often put through rigorous training. Some cities, such as Detroit, Michigan, had schools for this training to ensure a higher quality and consistency. While the horses were often unharnessed after arriving at the fire, they nonetheless had to bring the equipment dangerously close, which went against their instincts to turn around and flee. In addition to normal conditioning, the horses needed to be prepared for their duty. At the sound of the fire alarm, the stall doors of a firehouse were opened, either automatically or by hand. The horses were trained to bring themselves out of the stalls and position themselves under the cart harness, which was then lowered from the ceiling. Once they were secured, the horses would bolt from the firehouse, galloping flat out through the noisy and congested city streets.

This horse-drawn fire engine was used in Calgary, Alberta, circa 1905. Photo: Glenbow Archives NA-3220-3

A horse-drawn fire engine in Dawson, Yukon, circa 1899 – 1905. Photo: Larss and Duclos Office/Wikimedia Commons

Chasing the Bell

Often the horses were so well-trained that they answered the call to duty long after their “retirement.” Johnson tells one such story about a mare named Nell. When she retired from the fire service, Nell was pensioned off and used to cut grass at the local park, but her sense of duty remained strong. One night when the fire bell rang, she broke away and galloped downtown to the fire hall. Anxious to take her place under the harness, she was still pawing at the back door as the firemen arrived back from the fire.

From the Los Angeles Fire Department historical archives comes a story told by H.A. Herman. Herman grew up on a farm near Hannibal, Missouri, where his family sold and delivered milk. Herman recalls his father coming home with Old Frank, a horse he purchased shortly before World War I from the Hannibal Fire Department.

“He wasn’t our first horse to pull the milk wagon, but he was the best,” recalls Herman. “Old Frank, a Percheron, was nine years old when he got him, and had been through the training school for fire-horses, but had apparently gotten too old for that job.”

Related: Continuing the Bridle Horse Tradition

During a milk delivery early one morning, the fire bell at the station rang and Old Frank, still hitched to the milk wagon, took off at a full gallop, heading for the fire station. Joining him en route was his teammate Fox, who was also retired and had been sold to pull the milk wagon for a local competitor several blocks away. The two horses raced neck and neck down the street as if they were once again pulling the fire pumper wagon. However, the wheels of the two milk wagons became entangled, resulting in the wagons being dragged along on their sides for a half-dozen blocks with milk cans and bottles strewn along the streets behind them. Both horses came to rest at the closed doors of the fire station, ready to do their job, but appearing confused as the fire brigade had left without them. The horses’ behaviour was not chastised by their current owners; the horses had only done what they were trained to do.

A similar story from the City of Calgary Fire Department tells of one retired team of fire-horses that were in the process of hauling a load of pigs to the stockyard for a farmer, when a fire wagon came bearing down upon them with the alarm bell clanging. The farmer tried his best to restrain the two old horses who had become excited and wanted to run. As the fire outfit passed, they suddenly became young again, joining in the race to the fire, allowing nothing to stop them. The farmer hung on for his life as the wagon bounced and rattled its way to the fire, losing part of its load of pigs along the way. Once the horses reached the fire, they stopped and stood quietly, just as they were trained to do years before.

Related: Horses with Jobs: Barge Horses

Despite such rigorous training, the horses managed to find trouble from time to time. Cosman shares the story of the night the horses got loose at Toronto’s Old Portland Station. “The animals were housed in their stalls on the main floor of the fire station, while the men resided on the second floor,” she says. “One evening the horses managed to get loose and wandered upstairs while the men were eating dinner. But trying to get them to return back down the stairs was a different matter, as the horses refused to descend. The men were forced to use ropes, planks, and plenty of muscle power to slide the horses back down the stairs, all the while praying that the alarm wouldn’t ring.” Some cite this as the reason why firehouses were later built with circular stairways.

Imagine what it was like to see a horse-drawn fire engine rushing to a fire, pulled by an impressive team like this one (circa 1900). Only one in a hundred horses possessed the strength, speed, courage, and tractable temperament necessary for the fire service. Photo: Wikimedia Commons/PPOC, Library of Congress

First Portland, Oregon Museum of Art Building with horse-drawn fire engine passing. Circa 1910. Photo: Wikimedia Commons/City of Portland (OR) Archives

Related: The Heritage and Skill of Riding Sidesaddle

The Final Call to Duty

As the twentieth century began, so did the mechanization of fire brigades around the world. Slowly, automobile engines replaced the horsepower that had long guided the firemen to their task. While the Dalmations that had once run alongside the carts remained as a symbol of the firefighter, the horses they once protected and shepherded disappeared.

The Chicago Fire Department became one of the first in a major city to become completely motorized, and on an early Monday afternoon in February of 1923, their fire-horses were retired in style. A fire alarm box was pulled in the streets of Chicago, and a team of four well-turned out horses – named Buck, Beauty, Teddy, and Dan – pulled the old steamer engine out of the Fire Engine 11 firehouse for one last time as the crowd stood watching, cheering them on. This event was to commemorate the retirement of the city’s last horse-drawn fire engines.

Such stories of the retirement of the fire-horse brigades became common during the 1920s and 1930s. As with the mounts of police departments today, the end of a horse’s career was often met with the same reverence and respect offered to the firefighters themselves. Some, like the team of Sam and Prince from Purcell, Oklahoma, were buried and given monuments to commemorate their service, while others were given funeral parades through the city streets to allow the citizens to honour their heroes.

“Some cities tried to use the retired horses in less demanding jobs, like hauling water carts or garbage,” explains Cosman. “But these attempts were largely unsuccessful, since city employees found themselves forcibly dragged to fires whenever the horses heard the alarm.”

Just as the cities paid tribute to the fire-horses, the men who served with them had their own special attachment, and separating from their long-time companions was difficult. Hugh O’Neill, an assistant city Fire Chief for the Fredericton Fire Department in New Brunswick, who started as a horse driver with the department, remembered fondly the fire-horses’ contribution long after they had been replaced. A sentiment no doubt echoed by many of the older firefighters, O’Neill once remarked that “The old fire station just isn’t the same without that pair, believe me.”

“It was always a sad occasion when a fire-horse left his hall for the last time,” says Cosman. “The men would gather around to make a fuss over him and wish him luck. In some departments, it was tradition to send an old horse on his way with the same farewell as for all retiring firefighters: ‘Now you can rest; you have done your duty.’”

Excerpt from Good-bye to Canada’s Fire Horses by C.W. Green, Toronto Star, 1938

“Two little doors in the wall at the rear of the truck fly open and out dash Bill and Doll, two valiant four-footed firemen. Ears back and at the gallop they race forward. With braced legs they stop just at the right spot. The harness drops to their shiny backs. The hinge collars spring together with a click. The reins are snapped to the bits and they are ready to go – all in a few seconds.” ~ Courtesy of Fredricton Firefighters Museum

Remembering the Past

Over time, the memorials that paid tribute to the fire-horses have slowly deteriorated or vanished. The large red fire engines of the last 30 years required bigger and better firehouses; the old houses have been either converted and reconfigured or torn down completely, leaving no trace that horses once slept and worked in the same space as the firefighters. Even the phrase “like a fire-horse” has lost its reverence; today it means an almost blind and irrational passion for something, giving no credit to the horses for their bravery, hard work, and dependability. But as we begin to rediscover the large part these animals played in the growth of our cities and country, we begin to do them the honour they deserve.

“Nothing rivaled the [fire] horse for glamour and sheer excitement,” echoes Cosman. “By far the most colourful of any working animal, teams of fire-horses could empty stores and offices simply by the magic of their passing by.”

The Dalmation, Fire House Mascot

While tales of the fire-horses have faded into history, an important part of their story remains to this day. Dalmations have had a long history as working dogs, from their original breeding as shepherds and hunters to their more modern role as “coach dogs.” When the horse and buggy coaches of aristocrats went out, Dalmations often accompanied them. As firefighters began employing horses, Dalmations were brought on as an important addition to the team.

The dogs were bred with the stamina to run long distances, and their natural lack of fear allowed them to run alongside the horses without a problem. They were often used to keep the fire-horses on track, as well as keeping unwanted distractions from bothering the horses.

“In the older days,” explains Colin Johnson, retired Fire Chief of the Dundas, Ontario, Fire Department, “Dogs from around the city would chase the horses. The firefighters used the Dalmations to keep the other dogs away and allow the horses to run unimpeded.”

Besides aiding the horse teams to the fire, Dalmations were also used for security. Because horse theft was a common occurrence, as well as an expensive one for firefighters, the Dalmations were kept alongside the horses to ensure no strangers took off with them.

Related: Horses with Jobs: Carriage Horses

Related: A Country Built by Horse Power

Main Photo: Typical of the strong, level-headed fire-horses of yesteryear, a team of Percherons pulls the City of Victoria, BC’s Charles E. Redfern Waterous steam pumper on parade in Boise, Idaho in 2002. Photo: Frank DeGruchy, courtesy of the Victoria Fire Department, Victoria, BC