By Tania Millen, BSc, MJ

Wow, that’s a huge head! I thought, as a massive bison bull ambled toward me. He stopped 1.5 metres away, swaying his head back and forth, snuffling, seemingly undecided about what to do. Knowing that bison can weigh up to 1,000 kg and charge if provoked, I felt distinctly uncomfortable. The bull shuffled forward a few more steps and extended his nose to sniff the truck mirror, mere inches from where I sat in the driver’s seat. His almost metre-long nose and whopping shoulders were intimidating and I leaned away from the closed window, feeling unnerved. I was parked in the bison paddock at Waterton National Park in southwest Alberta, trying to get a feel for this species which was eradicated from the Canadian prairies over 100 years ago.

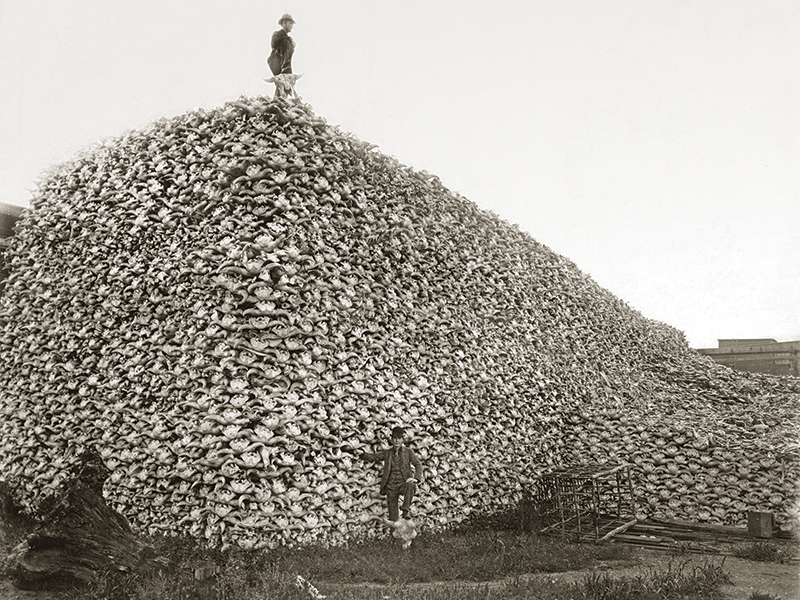

At one time as many as 30 million bison roamed the Great Plains, but by 1890 the population had shrunk to less than 1,000 animals. This photograph from the mid-1870s shows a pile of bison skulls waiting to be ground for fertilizer. Photo: Wikimedia Commons/Chick Bowen

Canada’s prairie country always seems barren to me, as though something is missing and the ecosystem is incomplete. Probably because it is. For tens of thousands of years, as many as 30 million bison formed the cornerstone of a complex ecosystem, which dominated the Great Plains. In 1890, bison were perilously close to extinction, with less than 1,000 animals scattered across the continent. Today, largely due to conservation efforts by Parks Canada, bison thrive in parks and private herds, worldwide.

During my prairie travels, scenes of horseback riders galloping across the prairie in clouds of dust alongside herds of thundering bison endlessly paraded through my imagination. Knowing those days are long gone, I was nevertheless enthralled by the notion of riding with bison. However, I’d dismissed the idea as a pipe dream. Impossible today. But eventually, I figured out that unpenned bison range in three of Canada’s national parks where horseback riding is permitted: Grasslands National Park in southwest Saskatchewan, Prince Albert National Park in northern Saskatchewan, and Banff National Park in Alberta’s Rocky Mountains. Excited to live my dreams, I promptly committed to what would become a multi-year quest to ride with bison.

Prairie Thrills

Due to its easy access, long views, and horse-friendly campsites, Grasslands National Park was first on my list of places to ride with bison. The park is split into two sections, or blocks, with the West Block located 120 kilometres south of Swift Current, Saskatchewan, near the town of Val Marie. Plains bison were reintroduced to the park in 2005, 120 years after they last roamed the area. Approximately 440 of them wander the fenced West Block portion of the park, often traipsing through the horse campsite located south of Belza day use area.

The author’s horse, tied to the sturdy bison fence at Grasslands National Park, ready to go bison hunting. Photo: Tania Millen

On the hunt for my first through-the-ears bison experience, I drove east for three days in early June, hauling a quiet but inexperienced four-year-old gelding. Having arrived at the park, I was unsure how the youngster would react to large dark-coloured lumps swaying across the landscape. So I changed plans, horse-camped outside the park, then drove in horseless to see the bison. It was thrilling to view semi-free roaming bison in a grassland setting, grazing, snoozing, and heaving themselves into dusty wallows to bathe. Although it was disappointing to not actually ride with them, the trip confirmed it was possible, and I was jazzed to try again.

Bison at Grasslands National Park in Saskatchewan. Photo: Tania Millen

Preparing for our bison-seeking trail ride at Sturgeon River Ranch. Photo: Tania Millen

On the trail at Prince Albert National Park. Photo: Tania Millen

Although the park isn’t on many bucket lists, two icons have put it on the map: Grey Owl, a 1930s-era conservationist, who lived with beavers in a cabin in the park; and hockey legend Gordie Howe, who considered Waskesiu, the park’s lakefront town, his favourite place on earth. But I was more interested in the park’s living legends.

Related: Reviving Ancient Horse Riding Skills

Due to the park’s distance from anywhere I usually go, I booked a day-long bison-seeking guided trail ride with Sturgeon River Ranch, which abuts the southwest corner of the park where the bison usually hang out. After three long days of driving in late June, I bumped down a sandy driveway between hillocky pastures, and parked by the ranch farmhouse. Assigned to a blonde bombshell mare named Dolly Parton, I joined guide Toby and a mother-and-daughter team from Prince Albert in riding along a muddy trail into the park.

We wound through mixed forests and knee-high grassy meadows, and snuck around myriad lakes and waterholes. We tracked bison through mud wallows, followed wolf and bear prints, and carefully peeked around copses of aspen, hoping to encounter the heavy woollen beasts. After much fruitless searching, we stopped for an off-horse brown bag lunch. As a storm boiled in the distance, we discussed whether to continue our search and risk getting caught in the thunder and lightning show, or beeline for the ranch. With the sky darkening overhead and wind increasing, we opted to ride home, having seen nary a bison. Although it was disappointing to be skunked a second time, it was eye-opening to experience another ecosystem where plains bison thrive, and pleasantly surprising to find such a wild place.

The cabin of Grey Owl, a 1930s-era conservationist who lived with beavers in Saskatchewan’s Prince Albert National Park. Photo: Tania Millen

The palomino mare, Dolly Pardon, looks around for bison as we stop beside a bison wallow in Prince Albert National Park. Photo: Tania Millen

Morning light at Elk Island National Park. Photo: Tania Millen

After saying goodbye to my bison-hunting partners, I drove west to Elk Island National Park. The park is located about 60 kilometres east of Edmonton and is the centre of bison conservation in Canada. While I was there, horseback riding was not permitted; however, in an exciting new development, horseback riders are now welcome to enjoy the park’s 11.6 km-long Hayburger Trail.

Since Elk Island bison are content to graze alongside the park’s thoroughfare, sightings are common and after many close-encounters-of-the-bison-kind, I was ready to continue my quest.

Although horseback riding was not permitted at Elk Island National Park during the author’s visit, sightings of Elk Island bison are common along the park’s thoroughfare. Photos: Tania Millen

Nap time in a wallow at Elk Island National Park. Photo: Tania Millen

Last Chance

After saying goodbye to my bison-hunting partners, I drove west to Elk Island National Park. The park is located about 60 kilometres east of Edmonton and is the centre of bison conservation in Canada. While I was there, horseback riding was not permitted; however, in an exciting new development, horseback riders are now welcome to enjoy the park’s 11.6 km-long Hayburger Trail.

Since Elk Island bison are content to graze alongside the park’s thoroughfare, sightings are common and after many close-encounters-of-the-bison-kind, I was ready to continue my quest.

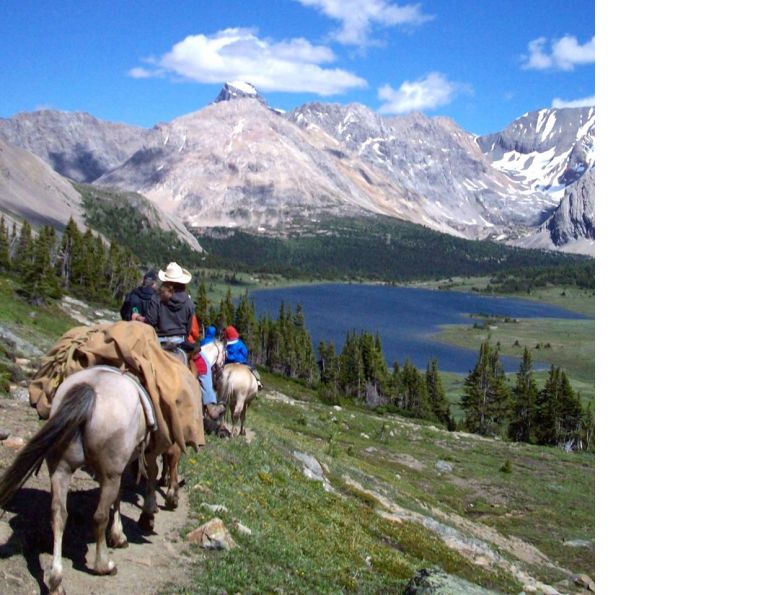

Banff National Park was third on my list of places to try riding with bison due to the remote location of the herd. The centre of the bison’s range is the upper end of the Panther River valley, which is accessible by riding for two days along a backcountry trail from the Panther River trailhead – itself located over 70 kilometres west of Sundre, Alberta.

Related: Solo Horsepacking Adventures in Canada's Southern Rocky Mountains

The bison’s range in Banff National Park is a two-day ride along a backcountry trail from the Panther River trailhead to the upper end of the Panther River valley. Photo: Karsten Heuer/Parks Canada

Lacking suitable horses myself, in mid-July I borrowed two mules from a friend and hauled them to the Panther River trailhead. After a relaxed night, I packed up one mule, saddled the other, and rode upriver for a five-day trip into Banff National Park’s backcountry. The well-used trail wound through pine trees and meadows, traversed the river, then passed a few horse campsites before shrinking to my favourite type of trail - untrammelled single-track. Nearing two prominent headwalls which signify the park’s eastern boundary, I stopped for lunch and my usual “gut check” to decide whether to continue.

My long-eared companions for a five-day trip into Banff National Park’s backcountry. Photo: Tania Millen

Unfortunately, things didn’t feel right. The mules were tired and getting girth galls, while a powerful storm was brewing in the mountains ahead. Retreat was the wisest choice. So, I turned around and walked the mules back to the trailhead, skunked for the third time.

What Next?

As rain battered camp that night, I considered what I’d achieved driving countless miles criss-crossing three provinces with horses and mules in tow, on a multi-year quest which to date had been largely unsuccessful.

Initially, the idea of riding with bison was a way to recreate romantic images of yesteryear - galloping across vast unsettled prairies teeming with bison, pronghorn, wolf, and grizzly. But I subsequently realized it was a way to alleviate my sense of loss – for the prairie ecosystem that is forever changed, for bison herds which will never roam free in large numbers again, and for everyone who wishes they could experience natural wonders that no longer exist.

I was incredibly fortunate to have an eyeball-to-eyeball experience with one of the largest wild mammals on the continent – even though it was through a truck window in a penned enclosure with a bull that was probably just interested in the hay stacked in my truck’s canopy. But I also experienced substantial joy learning about bison conservation efforts, riding spectacular new-to-me country, and knowing that it’s still possible to seek bison on horseback. (Even if you’re really lousy at it!)

Camping at the Panther River trailhead in Banff National Park. Photo: Tania Millen

Ultimately, it was disappointing to not actually ride with bison, but my heart is still in the hunt. I’m pumped to continue this quest and experience a piece of the past, while exploring what is, once again, the bison’s home and native range.

5 Tips for Safe Bison Viewing

- Carry binoculars and long-lens cameras.

- Consider how your horse will react.

- Stay 100 metres away.

- Do not pursue bison.

- Take alternate routes if bison block the trail.

Where to Ride With Bison

Banff National Park

Bison primarily roam the Panther River and Snow Creek valleys, accessible via pack trips along Panther River and Red Deer River backcountry trails. Follow Banff National Park Horse User Guide. Permits are required. www.pc.gc.ca/en/pn-np/ab/Banff

Elk Island National Park

No horse camping is available. Day riding is permitted along Hayburger Trail. www.pc.gc.ca/en/pn-np/ab/ElkIsland

Grasslands National Park

The horse campsite in the West Block near Belza day use area, has pens. Bison range through the site. www.pc.gc.ca/en/pn-np/sk/Grasslands

Prince Albert National Park

No horse camping is available. Sturgeon River Ranch offers guided rides or take your own horse for day or overnight trips into the southwest corner of the park. www.pc.gc.ca/en/pn-np/sk/PrinceAlbert, and www.SturgeonRiverRanch.com

Bison also range freely in the Sikanni River and Halfway River watersheds of northeast British Columbia, and in Yellowstone National Park in Wyoming. Riders are welcome in all these areas.

Riders can camp with their horses in American Prairie Reserve, Montana, and search for free-ranging bison.

A public bison round-up is held at Antelope Island State Park near Salt Lake City, Utah every October. Riders can take their own horses or rent from the outfitter to help drive approximately 600 bison into pens. Bison-viewing day rides are also available.

Related: Exploring the Historic Telegraph Trail

Check out more Holidays on Horseback.

Main photo: Banff National Park