Holidays on Horseback

By Tania Millen

Sven, the Haflinger pack pony, jerked his head up and snorted. I looked uphill towards our camp and caught a humpy flash of beige ducking behind a stunted fir tree. Grizzly, I thought. I was hand-grazing Sven and my paint mare, Jewel, on a frosty July morning in Mount Assiniboine Provincial Park, British Columbia during a solo pack trip. When Sven jerked his head up again, a beige grizzly bear shambled downhill towards us. Just 20 metres uphill from the first bear, a second bear rose up on its hind legs out of the brush before dropping down onto all fours and following the frontrunner. As the two bears lumbered towards us, Sven danced around on his lead line while Jewel kept grazing, and my heart beat a little quicker. As I considered what to do, a third bear trundled out of the trees and followed the first two. They were all grizzlies, all full size, and all coming straight at us. I started to sweat.

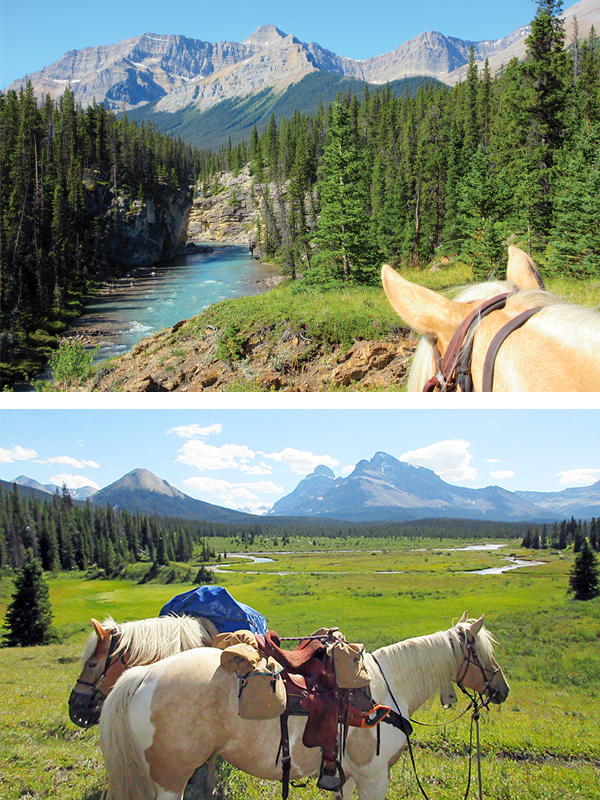

Mount Assiniboine Provincial Park (MAPP) is located in southeast British Columbia on the west side of North America’s continental divide and borders Banff National Park (BNP). In summer 2020, I decided to do solo pack trips in southern BNP and MAPP, traveling through areas I hadn’t previously visited.

The first trip started at the Mount Shark trailhead in Spray Valley Provincial Park, south of Canmore, Alberta where I tacked up Jewel, packed Sven, and rode west into BNP. The well-used Bryant Creek Trail was bustling with friendly hikers, and after a few hours I started looking for a campsite.

Packed and ready to go at the Mount Shark trailhead in Spray Valley Provincial Park before riding into Banff National Park. Photo: Tania Millen

My campsite on Bryant Creek Trail was an old horse camp with good grazing. Photo: Tania Millen

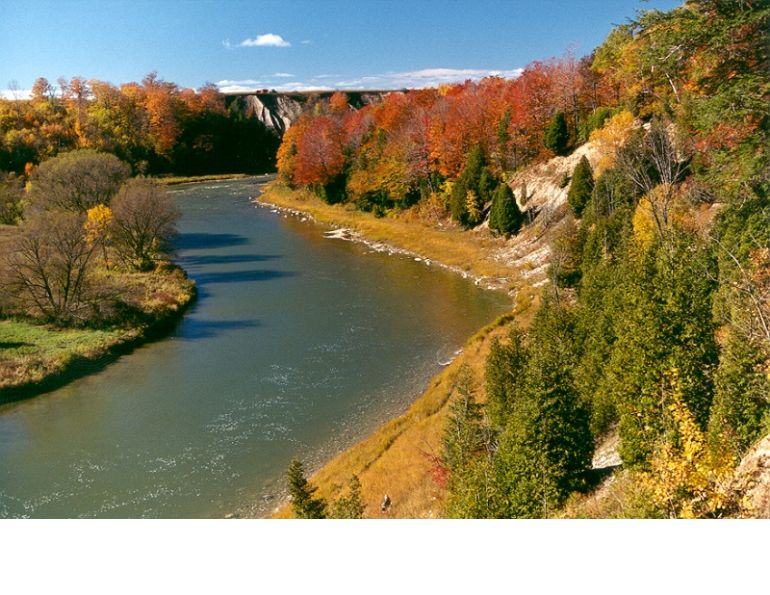

Many horse camps in Canada’s mountain parks were created in the early 1900s by hunters and outfitters and they still offer plentiful grazing, drinking water, and sheltering trees for today’s packers. However, today’s horses and riders require permits to camp in Canada’s National Parks, and horse camps can be challenging to locate as they’re rarely signed and some have been dismantled from lack of use. So, as we trekked along, I watched carefully for old blazes and limbed trees. When I spotted a little-used trail across a brush-filled meadow backed by tall trees, I followed it across a creek and into an old horse camp with knee-high grass and a hitching rail. After untacking the horses and hobbling them to graze, hanging my food bag on a purpose-built rail high in the trees, and pitching my tent, I flopped down by the horses to relax. Home for the night. The following day we followed the trail — signed as a grizzly bear thoroughfare — over the continental divide into the sub-alpine meadows of MAPP and a frigid snowstorm.

Related: Exploring the Historic Telegraph Trail

The Mount Assiniboine area was historically well travelled by First Nations, and photos of teepees beneath towering 3,600-metre Mount Assiniboine alongside cerulean Lake Magog are quintessential Canadiana. In 1894, colonial explorers traversed the area and Mount Assiniboine subsequently became a highly sought-after objective by mountaineers due to its classic pyramid shape and difficult climbing. The park surrounding the mountain was created in 1922 and remains popular with hikers and skiers, while the “Matterhorn of the Rockies” is still a prized achievement for climbers. Mount Assiniboine Lodge, the first backcountry ski lodge in the Canadian Rockies, was built in 1928 and still serves backcountry clientele, some of whom arrive by helicopter. However, I was sleeping in a tent at the designated horse camp while the stalwart horses were tied beneath nearby trees.

At 3,600 metres, Mount Assiniboine is known as the “Matternhorn of the Rockies” and is prized by climbers for its challenging slopes. Photo: Tania Millen

Sven watches the elk pass by the Banff Light Horse Association pens. Photo: Tania Millen

The storm left a trace of snow, which quickly evaporated in the morning sunshine, and I spent the day drying gear, watching climbers ascend Mount Assiniboine, and supervising grazing. The next morning the horses’ grazing was disrupted by three not-so-little bears.

As the bears trundled directly toward us, I decided to lead the horses — Sven snorting and dancing, and Jewel grazing — 90 degrees away from the bears’ route. In turn, the bears shifted their route so they were travelling away from us, too. When I realized they weren’t a threat, I stopped and watched them, awed by a close encounter with one of Canada’s most iconic species on their own turf where they are the apex predator and I am potential prey.

The day kept getting better, and I revelled in the good fortune of experiencing such a stunning place during a day ride through sparkling meadows under bluebird skies. We stopped for lunch at a viewpoint of Mount Assiniboine before returning to camp to nap in the sun.

On our fifth day, I packed up camp and rode back down the trail to explore more of southern BNP. It was a short ride to our previous camp in the timbers, but in the 30-degrees Celsius heat Jewel was soon sweaty and hiccupping. Concerned for her health, I sent a message via emergency SPOT beacon asking my designated emergency contact for information about horse hiccups. Apparently, horse hiccups or thumps are due to electrolyte imbalance and although Jewel looked fine a few hours later, I decided to end the trip to prevent further problems. The following morning I rode out to the trailhead, startling a mountain goat tiptoeing along the valley trail far from its safe cliff-side habitat — a lovely parting gift from the wilds.

After a few days of rest at nearby Etherington Horse Camp, we returned to the Mount Shark trailhead, packed up, and rode up the same trail again. This time our objective was the southernmost point of BNP — Palliser Pass — which is on the continental divide at the head of the Spray River Valley. The pass is named after John Palliser who, from 1857 to 1860, led an expedition across the prairies between Lake Superior and the Rocky Mountains in what was then Rupert’s Land.

There are roughly 65 grizzly bears in Banff National Park, and approximately 20,000 in Western Alberta, Yukon, Northwest Territories, and British Columbia. Photo: iStock/Don White

Sven and Jewel appreciated the good grazing at this campsite. Although permits are required to camp in Canada’s National Parks, horse camps are rarely signed and some have been dismantled. Photo: Tania Millen

Our trip was only four days: two days traveling to and from the campsite, a rest day, and a day ride up to the pass and back. The route included ten kilometres of forested single-track trail, followed by another ten kilometres of trail through serene meadows and vast swamps to a treed headwall. Above the headwall, a small lake was surrounded by talus slopes cascaded off the nearby peaks while a boundary marker indicated subalpine Palliser Pass. The trip was very relaxing, and at the end of it I felt ready for more challenges.

A boundary monument marks the Palliser Pass on the continental divide at the head of the Spray River Valley. Photo: Tania Millen

On the Baker Creek Trail near Lake Louise, heading up the Ptarmigan Valley toward remote Badger Pass. Photo: Tania Millen

After a few more rest days, I drove to Lake Louise with Jewel and Sven for a nine-day solo pack trip through BNP, and my fourth attempt at riding over 2,500 metre-plus remote Badger Pass, one of the highest passes in Canada’s Rocky Mountains with horse trail over it. Our first day was a scenic 18-kilometre slog up the Ptarmigan Valley adjacent to Lake Louise Ski area on well-trampled Baker Creek Trail, which passes the supposedly haunted Halfway Hut and provides access to historic Skoki Lodge. Both the hut and the now five-star lodge were built in the early 1930s to support ski-tourists and are formally recognized in Canada’s Register of Historic Places.

Halfway Hut landmark log cabin in the Ptarmigan Valley of Banff National Park was built at the midway point on the uphill trail to the CPR station at Lake Louise and the Skoki Ski Lodge, to provide overnight shelter for ski tourists on the way to the lodge. Photo: Shutterstock/Autumn Sky Photography

Jewel checks the view on the trail up to Pulsatilla Pass. Photo: Tania Millen

The next day was much tougher. After travelling a short, treed switchbacked section of trail south down to Wildflower Creek, we plodded upward through dense underbrush, washed-out trail, and challengingly steep sections before puffing into subalpine meadows below striking Pulsatilla Pass. After lunching with visiting marmots, I carefully led the horses across a hard-packed slippery shale side-hill high above Pulsatilla Lake. One slip of the hoof and the horses would have tumbled hundreds of metres into the water below. Following another rocky section, we topped out on windy Pulsatilla Pass, with its extensive views down the valley from whence we’d come. From there we crossed a lingering snow patch, slid down rock and grass slopes, then hustled through wildflower-strewn meadows along upper Johnston Creek, to the trail junction at Badger Creek. After poking around for an hour looking for the horse camp, I gave up searching and settled the horses in a meadow below the well-organized hiker campsite situated among massive, gnarled trees.

At the top of Pulsatilla Pass with the valley and Pulsatilla Lake in the background. Photo: Tania Millen

On our well-earned rest day, an evening storm blew into camp. Rain and wind battered the tent, swayed the trees, and worried the horses. Having fallen into an uneasy sleep, I woke in the pitch black to an animal sniffing and pacing around the tent. With my heart hammering and bear spray, bangers, and knife at the ready, I unzipped the tent, turned on my headlamp, and laughed in relief as a stout porcupine waddled by. My laughter quickly evaporated. Porcupines are well-known for chewing through salty tack and gear, plus could easily spook the storm-worried horses; however, there wasn’t much I could do but go back to sleep.

Related: Horse Packing Adventures in the Backcountry

A quiet dawn brought clear skies for our Badger Pass attempt, so I excitedly packed the horses and rode up the well-built trail, zigzagging ever upwards toward the peaks. When a grey grizzly bear ambled down the trail at us, I turned on the bell around Jewel’s neck and the bear melted into the forest. Eventually, we exited the trees and switchbacked up alpine shale slopes to a steep-sided, windy gap. I’d finally made it to the pass on my fourth attempt!

Jewel, wearing her bear bell, grabs a snack in Central Banff National Park. Photo: Tania Millen

Jewel and Sven at Badger Pass, one of the highest passes with a horse trail over it in Canada’s Rocky Mountains. Photo: Tania Millen

The sea of slate-coloured peaks covered by talus slopes dropping into a tight creek far below us was intimidating. It was country well-suited to mountain goats, not humans or horses, and was no place to dally. But a four-metre-high section of steep snow — remnants of a cornice — barred our route on the east side of the pass. I studied it closely before deciding that the horses could slide down it. However, there was no way back up, so if we slid down it, we’d be committed to traveling over 100 kilometres of wilderness trails back to a trailhead.

Deciding the risks were manageable, I led the horses to the lip of the snow embankment. Jewel followed unhesitatingly and glissaded down the slope behind me. But Sven stalled at the top before plunging over an almost one-metre snow ledge, like a big-mountain skier dropping over a cliff, and sliding straight down to the shale below. We were committed.

The trail dropped 500 metres in elevation down shale slopes, across subalpine meadows, and through forests to well-named Cascade River. A washed-out section of valley bottom trail resulted in us bushwhacking through bog and river side-channels before regaining the track. Then the Cascade River Valley opened up before us and Flint’s Park — the iconic central portion of BNP — emerged. At our camp adjacent to a creek and small meadow, I reflected on the day’s accomplishments and felt relieved to be travelling less-challenging trails through BNP for the rest of the trip.

Following the Cascade Road trail in Banff National Park. Photos: Tania Millen

With sunny weather and straightforward trails, the following five days had a relaxed rhythm. We followed the former Cascade Fire Road east then north to the Panther and Red Deer Rivers. The road was bulldozed through BNP in 1936 to help fight a forest fire, and was subsequently extended east down the Red Deer River to government-owned Ya Ha Tinda Ranch beyond the park boundary. It provided a quick route between Banff townsite and Ya Ha Tinda for park vehicles prior to its closure in 1984.

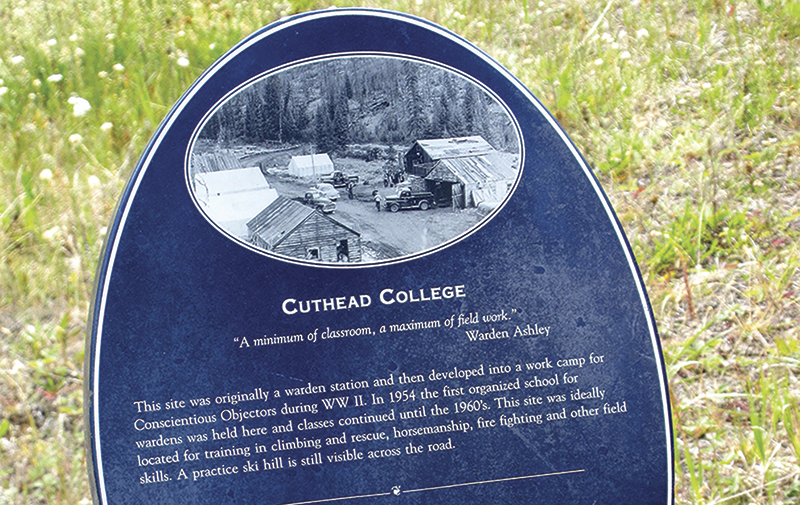

We rode past Cuthead Warden Cabin, a one-room overnight warden patrol cabin built in 1931, which is now registered as one of Canada’s historic places. Then we continued past the former site of Cuthead College where a warden station, work camp for World War II conscientious objectors, and a 1950s era warden’s school were situated. Marshy Widmore Lake marked the almost 2,000-metre pass between the Cascade and Panther Rivers and had been dammed by beavers, so the horses had to splash through 0.6 metres of floodwaters then walk over a sketchy beaver dam to regain the road. Finally, we reached the Panther River and a well-used camp with knee-high grazing that thrilled the horses. It was less than a kilometre from where 31 bison were released back into BNP in 2018, the first time bison had traversed the park in over a century, and I hoped to encounter some of the shaggy beasts. Unfortunately, they remained hidden during our trip, so I had to be content knowing that an imperative piece of the park’s ecosystem was back where it belonged.

The photo on the Cuthead College sign depicts the buildings of the former site where a warden station, a work camp for World War II conscientious objectors, and a warden’s school were situated. Photo: Tania Millen

Over the next few days, we rode north to the Red Deer River then west upriver along peaceful trails, through hordes of horrendous horse flies. One afternoon we arrived in a meadow where I thought there’d be a horse camp, but I couldn’t find any obvious sign of one, so I created a temporary camp for the night. The next morning I spotted a white skull high in a tree — a common marker, along with antlers, for a horse camp. I’d arrived at the right place but had just missed the signpost.

Riding upriver along the Red Deer River, and the picturesque Red Deer River Valley. Photo: Tania Millen

About noon on our ninth day, we arrived at the junction of several valleys just east of the popular Skoki area, where I’d planned to camp for one more night. But the horse flies drove us over 30 kilometres that day, out to the trailhead where we’d started the trip. We’d completed a full circle through the central portion of BNP, most of which I hadn’t previously travelled.

Tania Millen with Jewel. Every summer the author seeks out new backcountry trails to explore. Photo: Michelle LaFrance

It was a good summer. During three trips and 19 days on the trail, and through some of the most accessible country in Canada’s southern Rocky Mountains (and the best summer weather of the past 20 years), we hadn’t seen any other horses and riders. The prints I saw were of grizzly bear, bison, elk, moose, mountain goat, beaver, and in places near trailheads, human. Although we met and chatted with several backcountry hikers, every day I essentially just rode or hiked along enjoying the scenery and four-legged company, far from the worries of everyday life. It’s these experiences, plus sharing the wilds with heart-stopping grizzly bears and topping out on remote passes, that I continue to seek every summer. It’s a privilege that I hope more horseback riders enjoy, and in doing so will help keep backcountry trails, campsites, and grazing meadows open for horses and riders well into the future.

Related: On a Quest to Ride with Bison in Canada's National Parks

Check out more Holidays on Horseback.

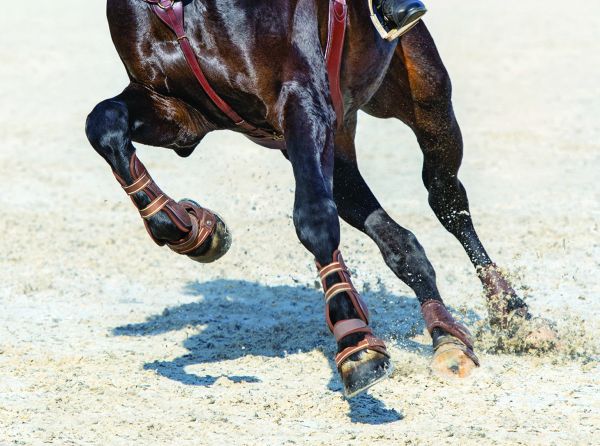

Main Photo: Shutterstock/Protasov AN