Source: UC Davis Center for Equine Health

Severe fires in recent years have exposed humans and animals to unhealthy air containing wildfire smoke and particulates. These particulates can build up in the respiratory system, causing a number of health problems including burning eyes, runny noses, and illnesses such as bronchitis. They can also aggravate heart and lung diseases such as congestive heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, emphysema, and asthma.

What is in smoke?

Smoke is comprised of carbon dioxide, carbon monoxide, particulate matter, soot, hydrocarbons, and other organic substances, including nitrogen oxides and trace minerals. The composition of smoke depends on the burned material. Different types of wood, vegetation, plastics, house materials, and other combustibles all produce different compounds when burned. Carbon monoxide, a colourless, odourless gas produced in the greatest quantity during the smoldering stages of the fire, can be fatal in high doses.

In general, particulate matter is the major pollutant of concern in wildfire smoke. Particulate is a general term used for a mixture of solid particles and liquid droplets found in the air. Particulates from smoke tend to be very small (less than one micron in diameter), which allows them to reach the deepest airways within the lung. Consequently, particulates in smoke are more of a health concern than the coarser particles that typically make up road dust.

How does smoke affect horses?

The effects of smoke on horses are similar to effects on humans: irritation of the eyes and respiratory tract, aggravation of conditions like heaves (recurrent airway obstruction), and reduced lung function. High concentrations of particulates can cause persistent cough, increased nasal discharge, wheezing, and increased physical effort in breathing. Particulates can also alter the immune system and reduce the ability of the lungs to remove foreign materials, such as pollen and bacteria, to which horses are normally exposed.

How to assess and treat smoke inhalation in horses

Horses exposed to fire smoke can suffer respiratory injury of varying degrees, ranging from mild irritation to severe smoke inhalation-induced airway or lung damage.

Knowing what is normal versus concerning can help you to know whether a veterinarian should evaluate your horse.

Respiratory rate at rest should be 12 to 24 breaths per minute.

Horses should be examined by a veterinarian if any of the following are noted:

- Respiratory rate is consistently greater than 30 breaths/minute at rest;

- Nostrils have obvious flaring;

- There is obvious increased effort of breathing when watching the horse’s abdomen and rib cage;

- There is repetitive or deep coughing OR abnormal nasal discharge;

- Horses should also be monitored for skin and tissue injury, especially for the first few days after exposure.

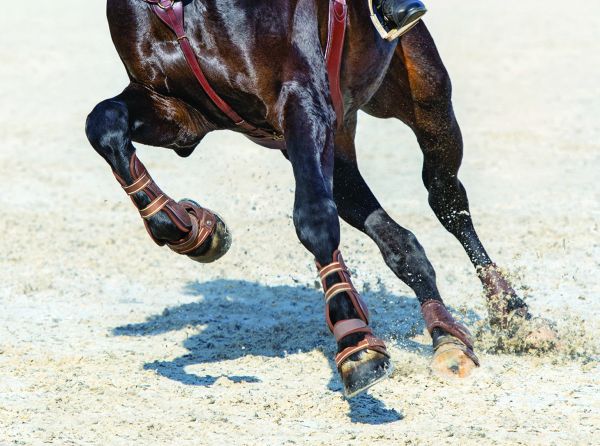

- Limit exercise when smoke is visible. Horses should not engage in activities that increase the airflow in and out of the lungs. This can trigger bronchoconstriction (narrowing of the small airways in the lungs).

- Provide plenty of fresh water close to where your horse eats. Horses drink most of their water within two hours of eating hay, so having water close to the feeder increases water consumption. Water keeps the airways moist and facilitates clearance of inhaled particulate matter. This means the windpipe (trachea), large airways (bronchi), and small airways (bronchioles) can move the particulate material breathed in with the smoke. Dry airways make particulate matter stay in the lung and air passages.

- Limit dust exposure by feeding dust-free hay or soak hay before feeding. This reduces the particles in the dust such as mold, fungi, pollens, and bacteria that may be difficult to clear from the lungs.

- If your horse is coughing or having difficulty breathing, contact your veterinarian. A veterinarian can help determine the difference between a reactive airway from smoke and dust versus a bacterial infection and bronchitis or pneumonia. If your horse has a history of having heaves or recurrent airway problems, there is a greater risk of secondary problems such as bacterial pneumonia.

- If your horse has primary or secondary problems with smoke-induced respiratory injury, you should contact your veterinarian who can prescribe specific treatments such as intravenous fluids, bronchodilator drugs, nebulization, or other measures to facilitate hydration of the airway passages. Your veterinarian may also recommend tests to determine whether a secondary bacterial infection has arisen and is contributing to the current respiratory problem.

- Give your horse ample time to recover from smoke-induced airway insult. Airway damage resulting from wildfire smoke takes four to six weeks to heal. Ideally, plan on giving your horse that amount of time off from the time when the air quality returns to normal. Attempting exercise may aggravate the condition, delay the healing process, and compromise your horse’s performance for many weeks or months. It is recommended that horses return to exercise no sooner than two weeks post smoke-inhalation, following the clearance of the atmosphere of all smoke. Horses, like all other mammals, tend to have an irritation to particles, but should recover from the effects within a few days.

- Air quality index (AQI) is used to gauge exercise/athlete event recommendations for human athletes. It may be reasonable to use those for equine athletes as well. The National Collegiate Athletic Association lists the following recommendations on their website: “Specifically, schools should consider removing sensitive athletes from outdoor practice or competition venues at an AQI over 100. At AQIs of over 150, all athletes should be closely monitored. All athletes should be removed from outdoor practice or competition venues at AQIs of 200 or above.”

For more information, see Findings and Strategies for Treating Horses Injured in Open Range Fires by Dr. Elizabeth Woolsey Herbert of the Adelaide (Australia) Plains Equine Clinic.

Printed with the kind permission of the UC Davis Center for Equine Health. The UC Davis Center for Equine Health is dedicated to advancing the health, welfare, performance and veterinary care of horses through research, education and public service.

Photo: Shutterstock/Tom Reichner