By Margaret Evans

Think "Chernobyl" and pictures of the nuclear meltdown from hell spring to mind. In the quarter century since, surprising things have been happening in the exclusion zone around the Ukraine’s notorious nuclear power plant. Plants and animals have returned and in some areas are thriving. But the region screams many vexing questions, none the least of which is the reason for the gradual disappearance of Przewalski’s horses that were released into the area in the late 1990s. And you have to question why an endangered species was released into such a hazardous area in the first place.

On April 26, 1986, a systems test at Reactor 4 of the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant near the city of Prypiat and close to the border with Belarus went catastrophically wrong. Following a sudden power surge, an emergency shutdown failed and a second more extreme power surge led to a reactor vessel rupture, then a series of explosions.

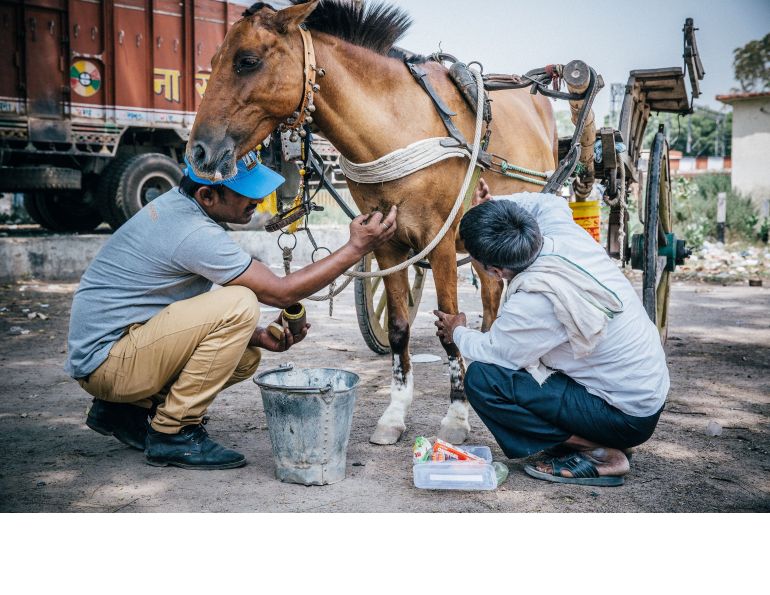

Przewalski’s horses were released into the wild near Chernobyl in the late 1990s and have since seen a significant decline in population. Photo: Tim Mousseau, Professor of Biological Sciences, University of South Carolina

The 1000 tonne sealing cap blew off the reactor and its graphite moderator was exposed to the air, causing it to ignite. The fire raged for nine days spewing huge quantities of radiation into the atmosphere that spread 150,000 square kilometres over the Ukraine, Belarus, and Russia. The wind carried radiation fallout as far away as Scandinavia. Later, a concrete sarcophagus was built over the damaged reactor to cover the contaminated remains. But construction was poor; the roof leaks and rain drains through the floor to spread contaminated water into the surrounding soil.

The exclusion zone was established very soon after the disaster and initially extended 30 kilometres around the plant. But its border was adjusted to accommodate areas of high concentration. The zone’s area is unevenly polluted and those regions most intensively affected were initially created from the fallout from wind and rain, and then because they were the sites for numerous burials of materials and equipment used in the cleanup. With the establishment of the zone, the government evacuated over 350,000 people.

Only authorized workers or permitted scientists were allowed to visit the abandoned area which, to everyone’s surprise, began to flourish. The region became a patchwork of pine forest, marsh, lakes, rivers, and grassland. With humans gone, wildlife returned. Populations of beaver, deer, moose, wolves, lynx, and wild boar were sighted and there have been traces of bears. Given that it was known that some regions were more contaminated than others, it seemed logical to some game managers back in the late 1990s that they could release the endangered Przewalski’s horse into the region.

“They (wildlife managers) had a refuge south of Kiev with quite a few Przewalski’s horses and nowhere to move them to and no way to feed them,” explained Dr. Timothy Mousseau, professor of biological sciences with the University of South Carolina.

“So someone decided to release them up at Chernobyl. There is this feeling that the radiation levels really aren’t that high so there’s the thought that maybe it’s not that dangerous. There hadn’t been any research done to show that it was.” Mousseau travels to the zone to conduct research work at least twice a year and the herd he had spotted around 2005 and 2007 has steadily declined which doesn’t bode well today since the Przewalski’s horse is already a species at risk.

The Przewalski’s horse is a tough, stocky, 13 hand, sand-coloured animal with an erect mane, no forelock, and a dorsal stripe running down the spine. It is the world’s last truly wild horse and, compared to the domestic horse that has 64 chromosomes, the Przewalski’s horse has 66 chromosomes. Most likely the two share a common, distant ancestor.

For millennia, Przewalski’s horses ranged throughout the Eurasian steppes from Eastern Europe through central Asia to China. It received its Russian name in honour of Colonal Nikolai Michailovich Przewalski, a renowned explorer who made several expeditions to Asia and reported sightings of the wild horse. But written records go back much earlier. A Tibetan monk made note of them in 900 BCE and Genghis Khan wrote of them in his Secret History of the Mongolians.

Hunting, capture for exhibits and private collections, military activities, competition with livestock for grazing, and severe winters took their toll on the population. The last confirmed sighting of the horse in the wild was made in Mongolia in 1969. It was thought they were gone forever.

Not quite. For decades, this endangered species had thrived in zoos and collections around the world. They had descended from a founder herd of 11 animals established in the early 1900s. A visionary decision was made to reintroduce the horse to its ancestral range in Mongolia and a release program was started in 1992.

For decades Przewalski’s horse survived in zoos around the world. In 1992 a plan to release the species to its original habitat in Mongolia was put into action.

It continued with a number of successful releases that saw the horses thrive, breed, and increase their population. But predation by wolves and the impact of severe winters were, and continue to be, a threat. It is no less so in Chernobyl but with the added hazard of radiation fallout taken up in the vegetation.

“I work on birds and there’s a big negative effect on the bird population in many areas,” said Mousseau. “In areas where there isn’t a lot of contamination, which is about a third of the zone, things seem fairly normal but when you get to the contaminated areas, the populations are really down. The same is true for the mammals. We did some tracking of mammals in the winter and that was very convincing. We brought a team over from Finland last summer to do some trapping of the wolves and it was the same basic pattern with big negative effects in the contaminated areas. As far as I know, no one has done any thorough census on the larger mammals such as the horses although there may be some literature, technical reports, that kind of thing, written in Russian by local people.”

Aside from predation, the possibility of poaching ranks high on the suspect list when it comes to the population decline of Przewalski’s horse. Many people in the Ukraine, especially those living around the exclusion zone, are poor and the opportunity for free horse meat is very appealing, no matter the hazards associated with a radioactive roast.

Nuclear plants use such isotopes as Strontium-90 and Caesium-137, which have half-lives of 29 and 30 years respectively. Both can cause serious or even fatal health problems.

According to the International Atomic Energy Agency there were over 100 radioactive elements released into the atmosphere when the reactor exploded. Most were short-lived and decayed. But isotopes Strontium-90 and Caesium-137 have half-lives of 29 years and 30 years respectively and are therefore still active in the region. Both have deadly health consequences.

“What I would like to do as a small project is an aerial count,” said Mousseau. “(We need to) find where the horses are and radio collar a few of them. You’ve got cell phone coverage everywhere. We could satellite track them for a while, get an idea of where they are, where they go.”

He said that, according to the locals, five years ago the population had risen to as high as 68 animals. But during his last visit he didn’t see any horses. Carcasses have been found so there is evidence of some poaching.

“We would try to track them via poop but I haven’t seen the big (stallion) piles. In the last few years we have seen hardly any poop.”

The biggest challenge is getting funding for further research and for the aerial count that Mousseau knows would be invaluable. But the priority in the Ukraine right now is to get a new structure over the top of the reactor and money for that is running short. Environmental research is a low priority, which means the endangered Przewalski’s horse in the Chernobyl region will remain vulnerable to threats for some time to come.

Main Photo: Tim Mousseau, Professor of Biological Sciences, University of South Carolina