By Margaret Evans

A small herd of Konik horses have found a curiously fascinating job in Scotland: They are eating some habitat back to health. At the Loch of Strathbeg nature reserve in Aberdeenshire, this unique herd of wild horses is grazing wetlands, opening up nesting areas for ducks, geese, swans, and wading birds.

The Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB), who manages the loch, decided to take a new course of action in conservation management, hoping to set aside the costly use of machinery and let the Konik horses do what their track record has showed they clearly excel at.

The loch is a wonderful wetland in northeast Scotland and a vital nesting, feeding, and migratory stopover site for waterfowl. During winter, 20 percent of the world’s population of pink-footed geese spend time there as well as lapwings, golden plovers, whooper swans, and barnacle geese. Formed in 1720 when a storm blew a sandbar across the channel flowing into the sea, it is 206 hectares in size and the largest dune loch in the UK. It supports 260 species of birds, 280 species of moths, over 300 different plant species, 18 species of butterflies, and more than 20 species of mammals.

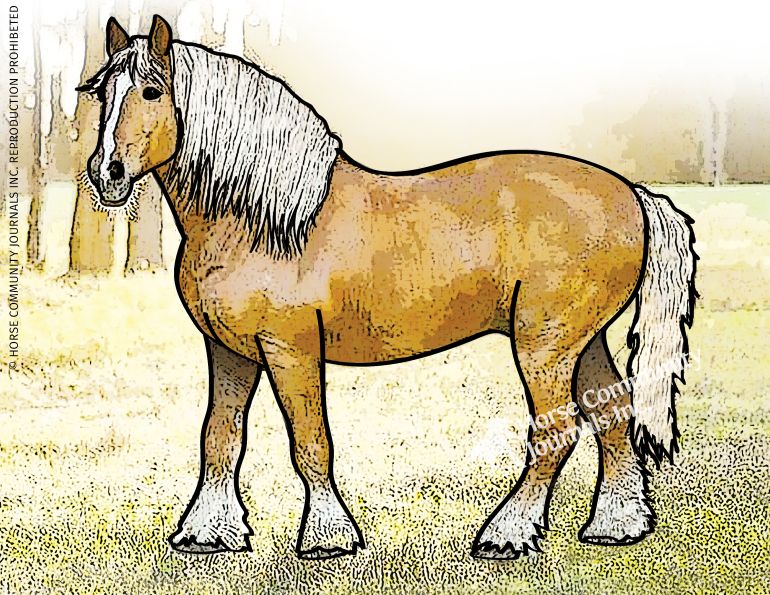

Konik horses were bred-back to be similar to the tarpan, Europe’s original wild horse. Koniks are tough, small, and hardy, grullo in colour, and amenable enough to be managed easily by conservation officers. Photo: Courtesy of Wildwood Trust

The concept of using large grazing animals in conservation projects is relatively new but in the last decade has proven to be enormously successful in Europe and the UK. The Konik horses are actually a breed bred-back to be similar to the ancient tarpan that inhabited the forests and wetlands of Europe and Western Asia for millennia. The tarpan became extinct around the turn of the 20th century, the last few being captured in Poland and put in zoos. European scientists, though, noted that domestic mares that ran in herds where the tarpan had formerly ranged continued to produce foals with tarpan characteristics, including mousy-grey colouring, dark manes frosted with white hair, striped forelegs, and a tendency to turn partly white in winter.

To bring back the tarpan type, they began a selective breeding program with mares and stallions exhibiting the strongest tarpan characteristics. The result was a tough, enduring, 13 hand high horse that could survive unhindered in harsh climates, thrive on some of the toughest vegetation, and yet be manageable and amenable to being moved about. The breed became known as the Konik, Polish for “small horse.”

Konik horses on the move to a new home, where they will help conserve and restore natural wetlands with their grazing habits. Photo: Courtesy of Wildwood Trust

Its greatest claim to fame is its choice of diet. Hardier than domestic horses, Koniks can thrive on coarser grasses, sedges, and rushes, thus helping to restore habitat and boost biodiversity.

Koniks were already being used in habitat restoration projects in Western Europe when the Wildwood Trust, a conservation charity dedicated to restoring woodland and grass ecosystems, partnered with the City of Canterbury in Kent, UK, to restore critical marshland along the River Stour. Over the centuries, the area had been lost to industrialization and urbanization. The decision was to bring back the Stour marshlands through conservation grazing using the Koniks.

The first 12 Konik horses were imported from Holland in 2002 and turned loose in the wetland region. They were not only joined by more imported Koniks in the following few years, but they settled and reproduced so successfully that eventually small groups were moved to other areas for habitat restoration projects. Most recently, eight Koniks ended up in the Loch of Strathbeg, Scotland.

“Koniks love eating rank, tussocky vegetation and we have lots of it at Stathbeg,” said Dominic Funnell, site manager at RSPB Loch of Stathbeg. “Currently we have to artificially strip it away to ensure our wetlands remain in top condition. But now, thanks to the grazing habits of these horses, we can ditch the machines and get back to an au naturel approach to habitat management. It’s great news for the geese, swans, ducks, and wading birds, like lapwings and curlew, that need wetlands to feed and breed, and it means we will have more time to concentrate on other conservation work.”

Herds of wild Konik horses are helping create new habitats for birds, insects, plants, and other wildlife across the UK. Most recently, they were introduced to Loch of Strathbeg in Scotland. Photo: Courtesy of Wildwood Trust

The secret to the Koniks’ success is not just grazing, but grazing intensively in small areas so their effects are long lasting. This way they can create areas of grasses, sedges, and reeds all at different heights, interspersed by grassy meadows. This plant mix and the heights of different plants stimulate a greater range of ecological niches. This in turn attracts birds that had become rare due to the loss of those niches. Along the River Stour floodplain, birds returned such as avocets, bitterns, egrets, redshank, lapwings, wagtails, pipits, owls, kestrels, marsh harriers, and merlins. Even rare plants germinated and took root such as sneezewort and ragged robin.

“These horses will be doing an important job for us, so, to make sure they’re not disturbed, they’ll be working on the less public areas of the reserve,” said Funnell.

The horses will be confined to certain areas of the reserve that need a more concentrated habitat management approach.

The growth of the concept of conservation grazers and the expansion of the Konik program has thrilled those at Wildwood.

“We’re delighted to be able to give these horses to the RSPB,” said Peter Smith, chief executive. “As a natural resource, the Konik horse offers conservationists a way of saving more wildlife for less money, saving charitable organizations and the taxpayer alike thousands of pounds as we recreate natural habitats for some of the rarest and most endangered species in the UK.”

Main photo: Courtesy of Wildwood Trust - Koniks used by Wildwood Trust to restore marshland in Kent have been breeding successfully, allowing the conservation charity to move small groups to other areas, such as Loch of Strathbeg in Scotland.