By Tania Millen, BSc, MJ

For generations, riders and horse lovers have been enthralled by the mystique of horsemen (and women), but many struggle to define what a “horseman” actually is. Is a horseman someone with a laundry list of skills such as starting young horses, nailing on shoes, being knowledgeable about horse care, and having the ability to train horses to the highest levels? Or is a horseman someone who lives in the moment, has mastered their emotions, and understands a horse’s mind? Perhaps a horseman embraces all of these attributes; perhaps none.

Xenophon’s writings On Horsemanship, are often considered the beginning of modern horsemanship. He was a Greek pupil of Socrates who lived circa 400 B.C. and wrote what is possibly the first definition of a horseman, stating:

Supposing a man has shown some skill in purchasing his horses and can rear them into strong and serviceable animals; supposing further he can handle them in the right way, not only in the training for war, but in exercises with a view to display [show]; or lastly, in the stress of actual battle. What is there to prevent such a man from making every horse he owns of far more value in the end than when he bought it, with the further outlook that, unless some power higher than human interpose, he will become the owner of a celebrated stable, and himself celebrated for his skill in horsemanship.

This description was a lofty ideal at the time. But in the past 2,400 years, as our understanding of horses and horse welfare has evolved, our definition of horsemen has changed, too.

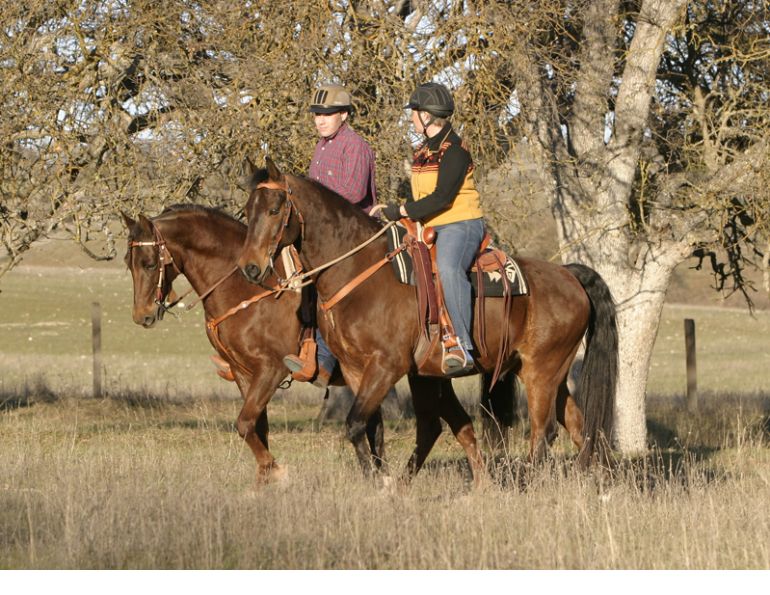

In an attempt to unravel what defines horsemen today I spoke with Denny Emerson of Tamarack Hill Farm in Vermont, United States (US), and Diquita Cardinal of Cardinal Ranch in Valemount, British Columbia.

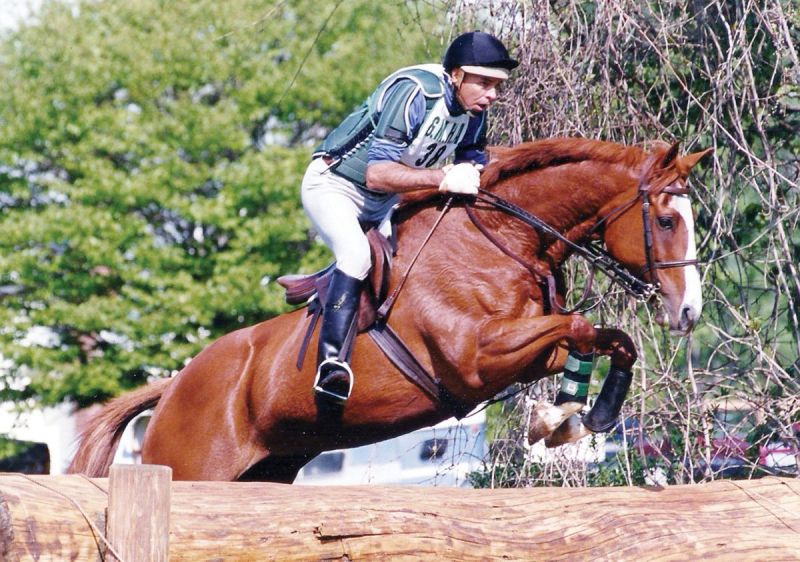

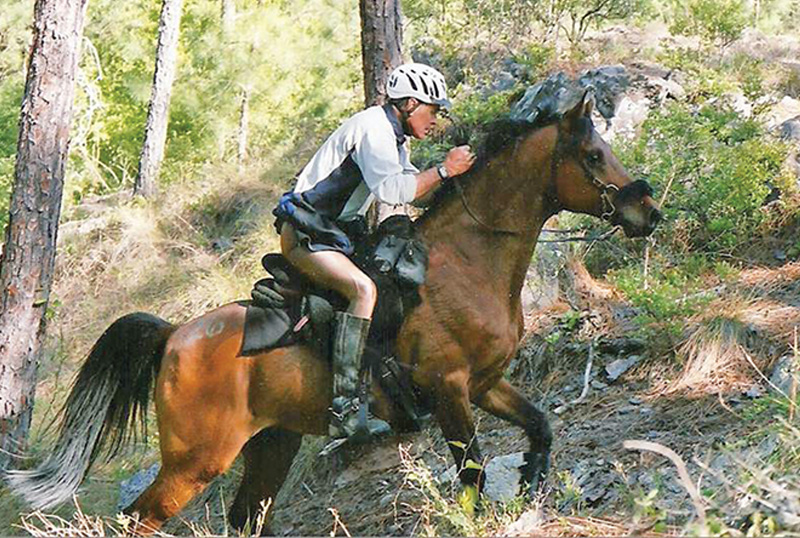

Emerson considers himself to be “someone who got a pony 70 years ago and has just kept going.” But he’s also a gold medal-winning member of the 1974 US World Championship Three-Day Eventing Team and a Tevis Cup buckle-winner having completed the renowned 100-mile endurance ride in 2004. In 2021 Emerson turned 80, but he still schools horses over fences, and — having three-day evented competitively at preliminary level and above for an astounding 50 consecutive seasons — seemed an appropriate person to ask about what defines horsemen today.

Related: Traditions in Horsemanship

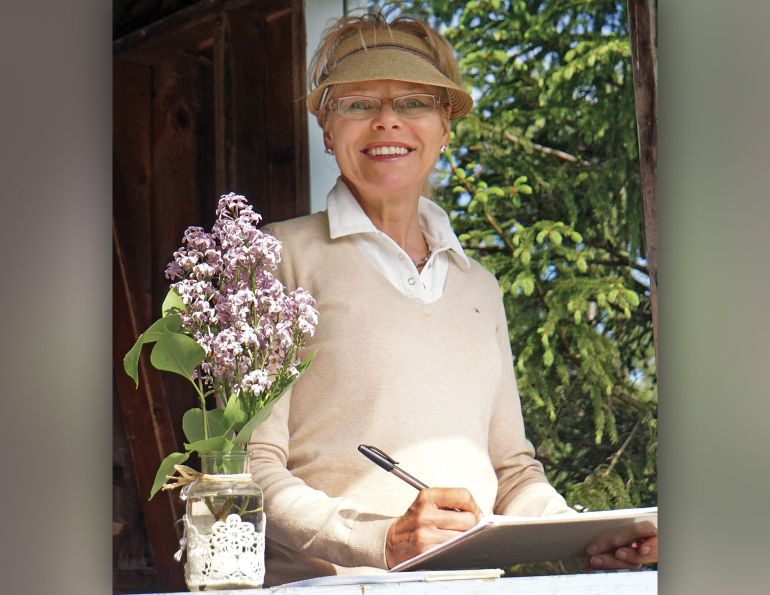

Diquita Cardinal says she is mentored by “a lot of old cowboys.” Photo: Cardinal Ranch

Diquita Cardinal is a 20-something Western-based rider and one of the youngest students to complete Level 4 of the Parelli Natural Horsemanship program. She’s a horse trainer and colt starter who grew up on her family’s ranch near Valemount, BC, where she operates her training business, has won the Chautauqua Ranch Rodeo 30-day Colt Start Challenge, and is mentored by “a lot of old cowboys.” Since Emerson and Cardinal are very different ages and life stages, plus have different backgrounds and experiences, I felt their views on what “horseman” means today would prove enlightening.

Emerson started our conversation by saying, “One of the definitions [of a horseman] that I was taught — maybe in 4-H in the 1950s — was somebody who puts the best interests of the horse first. It has to do with the care of the animal and attention to the well-being of the animal.

“I don’t think you have to ride or drive to be a horseman. I think there are probably some very, very good competitors who are not good horsemen, and there are people that have never ridden or driven who are great horsemen. So, I don’t think hands-on riding or driving affects the definition.”

Emerson then described how he thinks horsemen develop, saying, “The old-fashioned way [of becoming a horseman] was either you happened to be born into a family that had horses or you were a barn rat.” Unfortunately, Emerson thinks that today’s world is not very conducive to developing horsemen, saying, “[Becoming a horseman] is still an aspiration for some, but it’s a hell of a lot harder. At a certain point you have to be immersed in it. If you live in a suburb of a big city and your horse is 20 miles away, how the heck do you learn to be a horseman if your exposure to the horse is that limited?” He continued, “You have to hold horsemanship out there as a goal that is just as worthy as winning a ribbon at some show or finishing in the top ten in an endurance ride.”

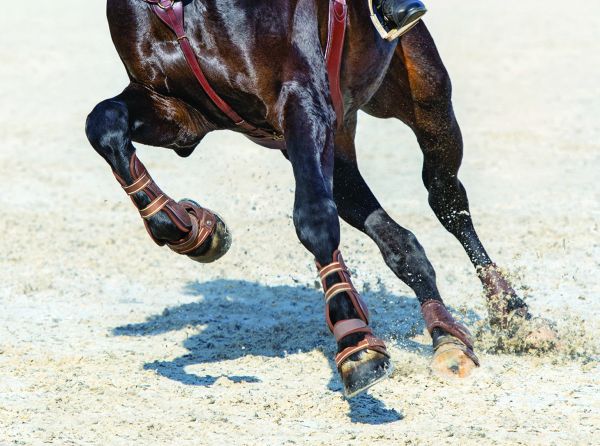

A gold medal-winning member of the 1974 United States World Championship Three-Day Eventing Team, Denny Emerson evented competitively for 50 consecutive seasons. Photo: Denny Emerson Collection

Denny Emerson turned 80 this year, and still schools horses over fences. Photo: Denny Emerson Collection

As further explanation Emerson says, “Putting the human need before the need of the horse… that is the opposite of horsemanship.” He explains that if one of us is not fit enough to undertake an activity, then we certainly don’t want to be forced to do something that makes us gasp for breath, drip with sweat, and get sore muscles. “But people do this to horses without even thinking about it,” he says. “They’ll leave the horse all week and then go out and ride on the weekend. It may be a joy ride for them, but it probably isn’t a joy ride for the horse.”

He provided another example, saying, “Let’s say you’re a really driven competitor and in a month there’s some big show, and your main goal is to do well at the show. As you get closer to the show, if your horse isn’t going well it’s very easy to start thinking of the horse as an impediment to the goal. And then you start to grind on the horse — ride them harder, whatever. But you take somebody else who is primarily a horseman, and their main goal is to get their horse going as well as it can, and the show is much less relevant. Therefore, Emerson says, “Thinking about what the horse is feeling and considering how your desires and motivations are affecting the horse — that’s being a horseman.”

When I asked Emerson if he considers himself a horseman he responded, “Yeah, but I’m more so now than I was when I was driven to win a gold medal and all that stuff. I’m much more careful of my horses now. I think sometimes it’s when you get a little older that you think What’s this horse going through?”

Related: Equitation Science

Denny Emerson on Cat at his first Advanced Event in 1971 at Dunham. The following year he was named the United States Eventing Association’s Rider of the Year. Photo: Iceprincess95/Wiki

Denny Emerson on Speed Axel at the Groton House Farm Horse Trials in 1999, his last Advanced event. Photo: Iceprincess95/Wiki

Denny Emerson doing an endurance ride on Rett Butler. Photo: Iceprincess95/Wiki

Although Cardinal struggled to define a horseman, she says it certainly includes putting the horse’s welfare first. She explained, “When I get on my horse I try to imagine how I can do the best thing for that horse. Not only bring them to their potential but just be kind to them. They’re a living being and they’re really sensitive animals. So, if I can be kind to them that day and not get a whole lot done, that’s not going to bother me. I try to leave my ego out of it as much as possible.”

Cardinal continued, “The goal [of a horseman] is to see how much your horse is willing to do for you and how much you can teach them to be a good learner rather than just how fast you can get them to spin or how long of a [reining-style] stop track you can make. Build their mind — their emotional state as much as their physical body — and teach them how to learn.”

Diquita Cardinal believes that being a horseman means putting the horse’s welfare first and teaching the horse how to learn. “I try to leave my ego out of it as much as possible.” Photos: Cardinal Ranch

She says, “A lot of times I think riders kind of run over their horse’s feelings [and get focused on maneuvers]. I try not to drill my horses. I try to have them think critically and ask questions where a lot of riders prefer that their horses don’t ask questions and just do what they’re told.”

When considering how good horsemen act, Cardinal says, “I look at the little things — like how someone leads their horse or bridles their horse — that tells me a lot about the relationship [between horse and rider].” Cardinal also agreed with Emerson that horsemen can be found in all parts of the horse industry, saying, “It’s a language and it can be on the ground; it can be with multiple horses at the same time.” She notes that there’s no timeline or end destination to becoming a horseman: “I don’t think there’s a shortcut to becoming a horseman. You can continually get better and keep learning. To me, it’s a lifelong thing — working on the art.”

“I don’t think there’s a shortcut to becoming a horseman. You can continually get better and keep learning. To me, it’s a lifelong thing - working on the art.” - Diquita Cardinal. Photo: Cardinal Ranch

It was encouraging to hear Emerson and Cardinal express similar views about what defines a horseman considering their vastly divergent horse experiences. They also both agreed that with the financial and performance pressures in today’s horse industry, producing quick results can easily become more important to many riders than putting horses first. However, just as Xenophon’s definition of a horseman was audacious for its time, hopefully, more riders and horse industry participants will decide that achieving the grail of becoming a horseman is well worth the effort — for both themselves and the happiness of the sentient beings we all cherish.

Related: Complex Rules Protect Canada's Horses

Related: Jonathan Field on Becoming a Horseman

Main Photo: Denny Emerson Collection