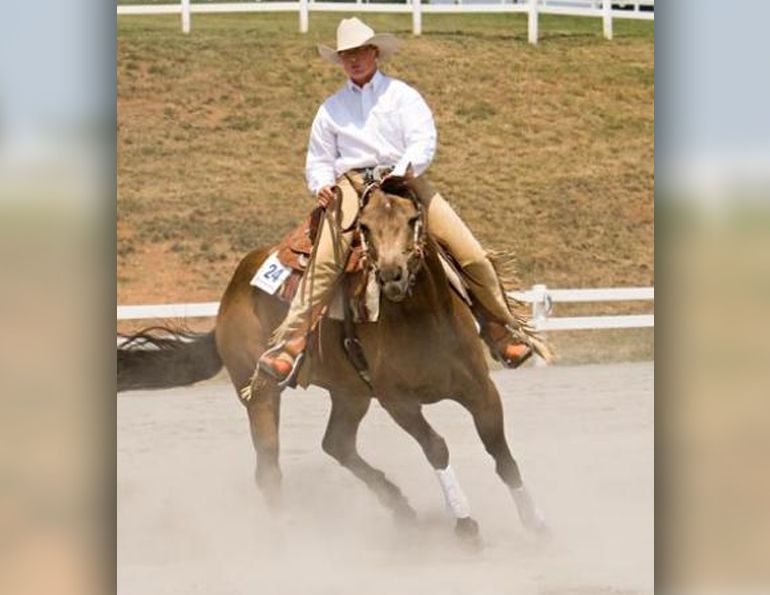

By Will Clinging

It has been a couple of years, but I am now back in business as a horse trainer and living on Vancouver Island, BC. My perspective has changed a bit over the last couple of years which I spent working as a cowboy outside Merritt, BC. As a trainer I used to ride a huge variety of horses. Some horses I would meet only once, some I would work with for a few months, but rarely did I get the chance to ride the same horse for much longer than that. They say variety is the spice of life but things can, on occasion, have a bit too much seasoning. My rides as a trainer were confined largely to a round pen or an arena with the occasional trail ride thrown in.

As a cowboy I used the arena more frequently to sort cattle than to train horses. I have ridden a lot in the past couple of years on my own reliable horses. This helped me realize that I still enjoy riding and allowed me to relax and accept the horses for what they were. I was not in trainer mode, I had a job to do and there was no time to be nitpicky about the little things that my horses did not do perfectly. There was not a lot of need or desire to keep improving their performance. As a result, I came to a real world understanding about what I could accept from my horses and they came to understand that I had certain expectations of them.

For me, these changes in perspective really drove home the need and desire to have a reliable horse. There is something about getting on a horse when you are absolutely sure it will be an enjoyable and safe ride. There is also something about getting on a horse that is not reliable. As an owner I want to ride, not train. As a trainer I expect consistent improvement so that one day the owner can get on and just ride.

I am not going to bore you with a long winded article about my philosophical approach to training. Instead, I am going to try to write articles about the horses I am working with and their specific situations. Hopefully, there will be information that will help to clarify the root cause of a change in behaviour or performance.

Over the coming months I will tell you about Jax, a six-year-old Friesian Hanoverian cross, and my current resident project. Jax has a few common, and relatively minor, issues. Unfortunately, these issues meant that he was becoming unreliable to ride and his owner was losing confidence which affected her enjoyment of riding.

When trying to figure out how to help Jax, or any horse for that matter, the first step is to figure out what is going on inside his head. To do this I work through a multi-layered assessment. I do need his personality profile, but don’t need to know a lot about his past. I don’t care how much training he has had or who taught him what, because somewhere down the line something happened that caused him enough stress that he needed to act out, causing his behaviour to degenerate. It could have been a specific incident, or an underlying situation that slowly got worse until it was obvious that something in his behaviour had changed.

I don’t need to know specific details, although they can help. I mostly need to know more about Jax the horse. Over the coming weeks and months I will discover many things, such as how sensitive he is to pressure; how confident he is when dealing with new, different situations or strange environments; what his established place is within a herd; whether he is energetic, bored, or lethargic; whether he is easily upset and fears correction; how he handles things like contact. The list goes on and on.

The answers to these questions will help me direct Jax’s training based on his strengths and weaknesses, although his weaknesses are more important than his strengths. I will spend much more time on things that he does not do easily or well, so that he can respond better and with less effort and frustration.

When Jax first came to me, I was still working on the ranch and did not have a lot of time to spend with him, so I don’t yet know him well. I know he’s a good looking horse with plenty of personality, and that he has basically good manners and likes to just hang out. However, under stress he throws tantrums, and has apparently bucked off a few people and learned that this behaviour can be effective. He’s also generally happier on the trail than in the arena.

When Jax first arrived he was on his best behaviour, not an uncommon response for a horse faced with strange surroundings, different horses, a new handler, and no established routine.

A few short lessons told me that Jax does not have as much confidence as he would have me believe. He is the low horse on the totem pole and not inclined to challenge other horses for more authority. This will possibly change over time as members of the herd get to know one another. His initial responses to cues, although basically correct, were slow and unenthusiastic. He wasn’t bored, but he had a dull, lethargic attitude and, although not totally unwilling, there was no enjoyment in him.

Gathering information from a horse is not done only in a round pen or arena. Stress factors show up everywhere. I was not, technically speaking, a trainer when Jax came to me and I still had a cowboy job to do so I had to use the situation I was in as part of my assessment of Jax.

While preparing for our move to Vancouver Island, I sold a couple of my own reliable, “can do anything on them” horses. This left me a bit short of horsepower to work with, so Jax had to go to work without as much training time as I would have liked to get to know him better.

Photo courtesy of Will Clinging

Heading out to the north end of Lundbom Lake, just outside of Merritt, I was ponying Jax behind me as I had a couple of days of not-too-tough riding. Jax came from the city and I was not sure if he’d ever seen a cow, so I didn’t feel it would be fair to put him under the stress of dealing with hundreds of cattle in a 2000 acre field, and quite frankly, I was not prepared to deal with that much stress myself. Jax, however, was great. He had a lot to think about but behaved very well, all things considered.

It was a different story when he had to go to work with just me for company. We had about 100 cow/calf pairs to move from the north end of Lundbom Lake, and Jax’s initial reaction was: I don’t think so. My response was: Too bad, we are here now and I don’t have time for your attitude so suck it up. He did and although not happy, he reluctantly went to work.

After an apprehensive hour of pushing cattle he started to settle. When we left the cows he relaxed considerably. We then found a much smaller group of cattle that also needed moving and by now he’d had time to think about what was happening and stayed much calmer. After we left those cattle he was happy as a clam, and in the hour it took to get back to the trailer he was quite wonderful to ride. The next day was basically the same – mild refusal, apprehension, work, and then relaxation.

Combining my initial observations about Jax having lower confidence and being non-challenging and not interested with his improvement over just a couple of rides, here’s what I learned:

1. Jax’s poor behaviour in the past is not well established, or at least it is part of his internal conflict with his desire to be a good boy;

2. Jax does not have a dominant personality;

3. There is willingness and even eagerness underneath the layer of seemingly bad behaviour;

4. If I can build Jax’s confidence and develop a stronger sense of responsibility in him, he will be a great horse.

Once I have found and helped Jax strengthen some of his weaker areas, I will start to incorporate these improvements into the things he already does well to find something he can excel in. We all have something we’re good at, and being good at something makes it easier to continue to improve until we reach a level where we have a mutual understanding about expectation, performance, and tolerance. By that point, Jax should be that reliable “can do anything on him” horse that we look forward to riding.