By April Clay, M.Ed., Registered Psychologist

Have you ever wondered how other people view your resilience as a rider? Are you known as the “comeback kid,” or the “choker”?

“I am pretty sure I am known as the ‘snow-baller.’ In fact I know I am. One mistake turns into another and another and I just crater. I hate that about myself!” said Jill, a junior rider with big aspirations. She knows all too well that she has to find a way to develop the hardiness associated with elite level riders if she wants to reach her goals.

Jill is not alone. There are a lot of riders and other athletes who lack the ability to turn around a poor decision, mistake, or bad ride. You don’t have to be one of them. With some work, you can improve your comeback potential.

Shift Your Perspective

One core thing all mentally resilient riders share is a very particular perspective on adversity. They are more likely to think of difficult circumstances in terms of opportunity. If the same error keeps reoccurring in training, this kind of rider might think: “I love puzzles, and once I figure this out I’m going to be that much further ahead.”

If they suffer some bad luck and their only horse is suddenly injured: “How can I best use this time? Maybe I’ll ask around to see which other horses are available to ride.”

It’s not that these riders are ultra positive pie-in-the-sky types; they just think differently. They know that less than perfect is what sport is all about — especially horse sport, where you are dealing with so many variables. The riders with the most comeback potential are not surprised at all by adversity. They expect it, embrace it, and use it to their advantage… and to other riders’ disadvantage. They can easily steal away a placing or even a win, not because they ride better but because they think more efficiently.

So really reflect hard and confront yourself about what challenging circumstances mean. No one is forcing you to see them as horrible, irreconcilable failures. That is your choice. If, like Jill the snowball, you are someone who could stand to tweak your view on errors, be willing to try something different.

In training, when you encounter an error, either encourage yourself to smile right away or cue up a phrase like “great, now what?” Both will help you change what has come to be your initial conditioned response, to stop and berate yourself. For Jill, this was crucial to her transformation into a comeback rider.

“I had to learn not to take myself and everything that happened so seriously. It was as if every bad thing that happened I magnified in my head ten-fold. Then I was so busy moaning about how bad everything was I actually just forgot to ride. I forgot to fix things,” she said.

The real truth about mistakes is that they will inevitably happen. Sometimes you will need their assistance to further your learning. Sometimes you will want to, and need to, let go of them as fast as smelly garbage. Observe one of the most resilient riders you admire and watch the way they handle their errors (yes, they do make them). Watch the way they handle frustration, disappointment, and losing.

Through your observations, you will likely pick up on this: the comeback kid type doesn’t judge. They don’t get themselves tangled up in good and bad. They stay focused on pulling out whatever information they need to keep moving forward. They stay on task.

Practice Deliberately

Can you practice being the kind of rider who can bounce back from anything? Absolutely. In fact, you should relentlessly and deliberately practice it.

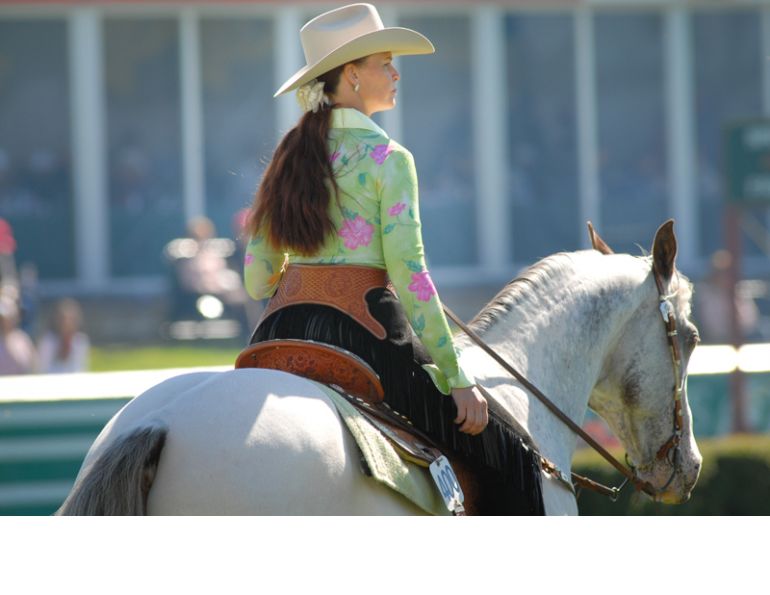

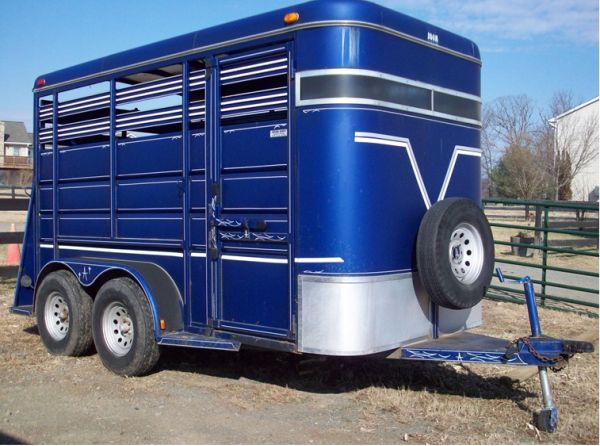

Practice bouncing back from a setback as often as you can. Teach yourself to pause and refocus your thoughts to those more positive and encouraging. Photo: Robin Duncan Photography

You may have heard the expression “practice makes perfect.” You may have also heard this clarified to “perfect practice makes perfect.” In other words, you have to watch carefully what it is that you practice every day, because you may well be training yourself to do the wrong thing. You may be putting in hours of sweat-inducing, mind-bending practice, but if it’s not correctly targeted, your efforts will be for naught.

Jill discovered that she was guilty of this. She practiced; she practiced a lot. However, she was an unfortunate master of rehearsing the wrong things. For example, every time her horse challenged her authority she would get angry with herself and simply stop riding. This would create more horse-related problems that spun out of control. She was teaching herself that she could not take charge or claim leadership — over and over. She was teaching herself to quit again and again.

So Jill decided to try a new practice. Every time she felt challenged by her horse she took a huge breath, let it out, and said to herself “step up.” To her, this meant step up and be a leader, even if you make a mistake. It took some time, but she began to go through the tough times instead of slinking away from them, and because of that her confidence grew.

So the first step in deliberate practice is to come up with a process. When things happen that you don’t like, that frustrate you and turn your brain to negative mush, how will you cope?

The best first step is to find a way to pause, especially when you are first beginning to try something different with your thinking. As soon as you find yourself having that old familiar “I want to give up” feeling, find a way to mentally stop yourself. It doesn’t have to be a long pause; just long enough to acknowledge that you recognize what’s happening and know you’re about to steer yourself in a different direction. If appropriate, you could stop your horse, or take a deep full breath in and blow it out.

A pause can also come in the form of containment. Try visualizing parking the error or thought in a stall or container. The message to you: put it away and take it out for the purpose of understanding when it’s more appropriate.

This first part of the process is crucial because it effectively interrupts your usual response, your habitual thinking. Once you have derailed your usual process, you can then make way for something new.

The second part of your process will have to do with refocusing your thoughts and ultimately your direction. Here you need to decide what your new thinking will involve. Will you encourage yourself to look for the opportunity? Will you boost your positivity by saying something like “you can, you go!” to yourself? How about directing yourself back to the job at hand by naming what you want to attach your brain to: “straight horse, eyes up, even pace.”

Lastly, give your new process a name. It’s an important part of a new skill set for you and one that will ultimately change the way you and others view you as a rider. Call it the “turn-around,” the “reboot,” the “reset,” or even the “comeback.” Jill called hers “the bulldog.” Call it whatever you like, as long as you know what it means and how it’s done.

Make sure you practice your process. Teach it to yourself. Make it so familiar that it doesn’t require much conscious thought. Create a new habit that becomes part of your repertoire. Then others will most surely say, “Wow, there she goes again. She really turned that situation around. But that’s just the kind of rider she is.”

To read more articles by April Clay on this site, click here.

Main photo: Robin Duncan Photography - If something goes wrong on your ride, how will you react? In order to have good comeback potential, you must learn to think about setbacks as opportunities.