By Kevan Garecki

The biggest risk factor of a horse sustaining injury during transport is due to inadequate or improper training for loading and hauling. The key to avoiding these injuries lies in investing the time to teach the horse in a way that suits his learning style. It's important to keep in mind that, as with any form of teaching, if one method isn't working, there are plenty of other strategies to try. The alphabet still has 25 letters if Plan A does not work!

Two essential principles to remember when training a horse to load are patience and flexibility. Don’t get fixated on one method or get frustrated if it doesn’t work right away. Consistent practice is key to reinforcing the lesson so the horse fully understands what is expected.

Horses and humans differ in the ways they respond to stimuli. Once a horse experiences something frightening, it’s not something he will easily forget. Our job is not to eliminate all fear, but to help him manage it. It’s far better to prevent fear from developing in the first place than to try to correct it later. The first time a horse encounters something new should ideally be a positive experience, building trust for future lessons.

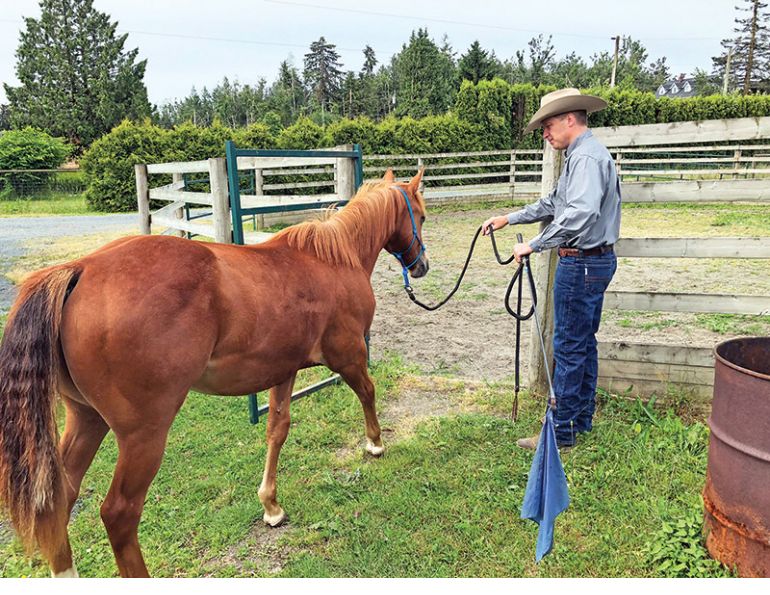

For horses new to trailering, the loading phase provokes the highest amount of stress, which makes it crucial to keep this phase calm, controlled, and without unneccessary stress.

For the horse new to trailering, the loading phase is by far the most stressful part. Photo: eXtensionHorses/Flickr

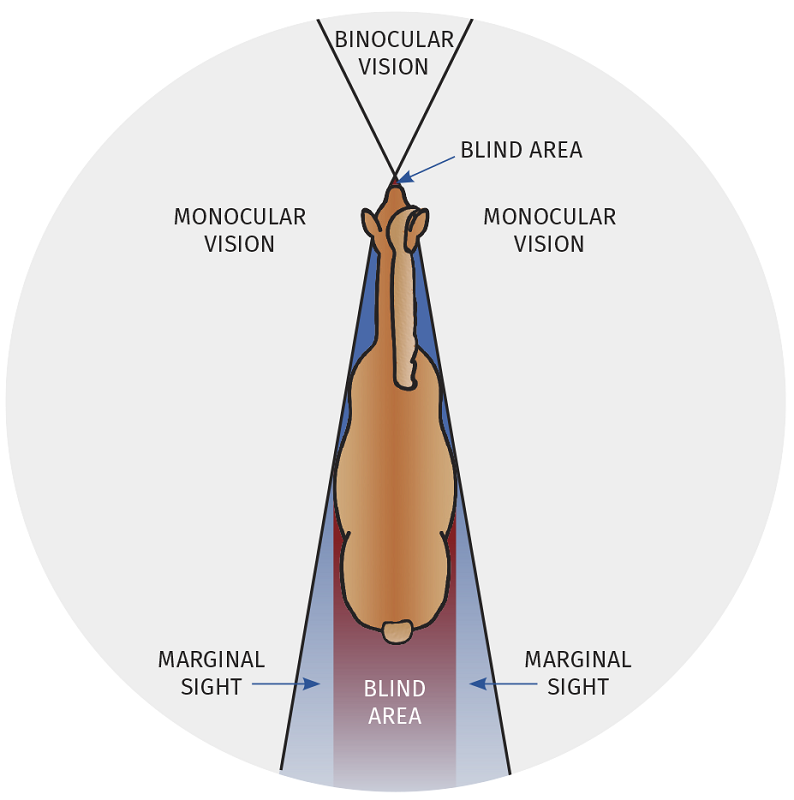

When working with horses, it helps to understand how the horse sees things. The horse’s depth perception is not as acute as ours; although they can often discern details at much greater distances than we are capable of, they are often unable to determine exactly how far away something is. This is a clue as to why they approach new things slowly, and why they need to stop and look at a trailer’s ramp or step-up. It’s also why they may spook at something whether it’s right next to them or a meter away, or mash you against a wall as they pass by it. They’re not blind, silly, or pushy – they just don’t see things the way we do. Horses also see details that we often miss: A wheelbarrow placed a few inches left of where it was yesterday, a regular visitor wearing a different hat, or a subtle scent on the breeze are enough to put many horses on alert and ill at ease.

The horse vision image (Figure 1) provides some clues about what horses can and cannot see. Note the large blind area directly behind the horse and the smaller one immediately in front of the muzzle. The horse’s binocular vision (ability to see simultaneously with both eyes) is limited to a narrow field directly in front of their head. Keeping these attributes in mind can assist us in helping the horse see what we see, and allow us to predict what situations might elicit a spook.

Figure 1

Take note of the inordinately large monocular regions on either side of the horse’s head. The horse is capable of collecting audible and visual signals from both sides simultaneously. This information is processed directly from the eye or ear receiving it, which quite literally means that the horse can see out both sides of its head at the same time, and assess this information independently. So if your horse spooks at something, try looking on the other side; he may have seen something you didn’t.

Related: Inside Your Horse Trailer

Realistic Expectations

In a perfect world, every horse would already have sufficient trust in us to follow wherever we might lead them. A common misconception is that if the horse went into the trailer yesterday, he should hop right in today. Some horses will, some won’t, yours might. Expect minor setbacks and build on those instead of chastising the horse for misbehaving. If the last loading session went well (and you were savvy enough to end it there on a good note), but today the horse has doubts, taking a step back to cover the same ground again is not a defeat. It’s just giving the horse another chance to verify the trust he has in you. The most effective way I’ve found to minimize these setbacks is through consistent practice. No different than any other training exercise, the repetition allows the horse to identify the routine, determine what it is we want, and test our response to see if he’s doing what we’ve asked. Think about that last part carefully. You will be standing next to one of the most perceptive creatures on the planet. Everything you do, everything your body does, even how you breathe and where you look, is being assessed by that horse.

Lip chains, butt ropes, treats, and coaxing all have one thing in common: They are all excuses for our own failures. If you were riding your horse and you had to give him a treat to get him to turn left, would that be an acceptable situation? Does using a chain over his gums to get him to stop sound okay? What about tying a rope to his back leg to get him to walk forward? I shake my head in amazement that these examples sound so absurd, but using the very same techniques are considered acceptable to get a horse into a trailer.

I like to approach loading in much the same way I would a desensitizing exercise. The idea is not to scare or intimidate the horse, but rather to create an environment in which the horse becomes a willing participant. By forcing, coercing, or tricking a horse into a trailer, we only make subsequent attempts that much more challenging. As any athlete will testify, one must prepare the body for exercise and exertion before a vigorous workout. While trailering shouldn’t be physically demanding, it can be a daunting mental challenge for many horses. I begin with some simple ground exercises – having the horse yield the fore and hind respectively, back on cue (verbal or physical), and stand still for a given length of time. This prepares the horse for the exercise by establishing the necessary authority, and gives me a peek at what’s going on inside that beautiful head. For everyone’s safety, I need to know that I can rely on the horse to do what’s asked of him. The horse in turn gets to do some simple tasks, which will help him understand that I’m not going to ask him to do anything he’s not capable of. I get obedience, he gets confidence, and we both get trust.

Keep in mind that when the horse steps in, but backs out quickly, there is no more a defeat than having the horse step in was a victory. The horse needs to know he has a way out, and it’s okay to let him have that avenue of escape in the beginning. While many will consider letting the horse back out to be losing, in fact what we will eventually accomplish is proving to the horse that he can rely more on our judgment and less on his escape route. Holding the horse or restraining him in an uncomfortable situation can turn off any rationality that may have been present and switch an exercise into a fight for survival. If you don’t have the horse’s mind on your side, you have nothing.

One common mistake that deserves to be revisited is when to close the door. Once you have the horse walking onto that trailer calmly, the best way to screw it all up is to slam the door on his butt. This will only serve to reinforce his fear that you have just trapped him. Ensure the horse knows he can step off at will, then work at having him stand calmly inside for longer lengths of time before trying to close that door or confine the horse with a divider. Every horse is claustrophobic, some just hide it better than others. This phobia is one of the primary triggers that sets off a horse’s fear response when loading (suspicion or distrust of the unknown being the most prominent). Understand that no matter how much the horse trusts you, you are asking him to do something completely contrary to his basic nature. Approach trailering as you would any other training: Keep it simple, and break the lesson into small parts. Ensure that the horse understands what’s being asked of him; give him time to process both the request and the actions he has to make in order to comply. Keep the lesson positive. If you hit a snag, repeat some part the horse did well, then leave it alone for the time being. There should be no force; the key to trouble-free loading is willing participation.

Some horses can be extremely aggressive, but this doesn’t always mean they’re trying to be the boss. More often than not, aggressive behaviour is a mask for fear. Remove or minimize the fear factor, and you will almost certainly discover a horse who is far more manageable and willing to participate. If a problem persists, go take a look in the mirror instead of in the paddock! Most horse problems are really people problems. Never chastise a horse for acting like one. Every time we force a horse into a trailer, we add another brick to the wall that they just might hit the next time. Each time we allow the horse to make up his own mind about the trailer, we increase the likelihood that he will step on next time. And remember, the time to teach the horse to load is not the morning of the show when you’re running late.

GETTING STARTED

This may sound elementary, but never attempt to load a horse into a trailer that is not properly hitched to a suitable tow vehicle.

Groundwork

Here are a few steps I consider essential for introducing a horse to load:

- The horse must at least respect your space enough to not intrude into it. If you can’t control the horse on the ground, you’re asking for trouble trying to squeeze him into a little tin box.

- The handler must have the confidence to direct the horse to wherever he wants, and be able to have the horse stay where he has been parked. If you can’t muster the moxie to be the boss, then find someone who can. Anything less is dangerous for you and the horse.

- Leave your watch in your pocket. We subconsciously convey our time constraints to Jack, which proves that we’re not really there for him.

- The best scenario is to park the trailer in an arena or other large but fenced space; if that’s not an option, backing up to the gate of a round pen works well, too. The idea is to show the horse he has an out if things get to be too much – but the space is still relatively confined in case something goes wrong.

- Patience, patience, patience. If you don’t have it, farm this project out to someone who is tolerant enough to get the first step done right.

I like to start these sessions an hour or so after everyone has had breakfast and the morning chores are done. Things are just a little calmer around then; there is no worry about rapidly changing light conditions or about getting to other chores. Try to park the trailer in such a way that the entrance is well lit, but out of direct sunlight. Remember that while horses have greater visual acuity than we do, it takes them longer to adjust to changing light. I frequently see horses balk at the doorway of a trailer and discover it’s because they’ve been led up to the trailer in bright sunlight and they can’t see inside properly. If you think the light conditions may be affecting the situation, give the horse a moment at the entrance to allow his eyes to become accustomed to the darker interior.

Related: Incidents on the Road

Horses often balk at the doorway because it takes their eyes longer to adjust to the lower light inside the trailer. Don’t be discouraged if the horse stops to “read the horsey newspaper” of smells and sights inside the trailer. Convey your patience with relaxed body language. Photo: Carter/Flickr

Think about where you’re standing when loading the horse. Assume the same position you would have if leading the horse across open ground. This should be directly beside the horse’s head, and some horses may be more comfortable being led with the handler at their shoulder. Either position is acceptable, so long as you always have an out if the horse spooks. If your horse is used to being led from his side, think about how he will feel when you’re suddenly facing him and hauling on his head. Doing this sends the horse mixed signals: On one hand we’re pulling on the lead rope saying “Come here!” but the horse sees their human face to face, which (as the horse learned during “Manners 101”) means “Stay where you are,” or even “Back away.” While most horses can develop a vocabulary of verbal cues they understand, they are more attuned to body language and so will often regard those nuances with higher importance than we might think. Always be aware of what your body is telling the horse – your posture and focus are important. When leading a horse up to the trailer ramp or step-up, I never look at either. Instead, I look into the trailer at the place where I expect the horse will be in a moment. If we look at the ramp, the horse will either regard that as the destination, or wonder why you’re looking at it so intently, figure there must be something wrong, and stop right there. You’re the one leading the horse, so make sure you’re an effective leader. Don’t be discouraged when Jack simply puts on the brakes. He may want to test all of those interesting smells; I call this “reading the horsey newspaper.” You can convey your patience and promote a relaxed atmosphere by emulating what horses do when they’re relaxed: Stand side by side, one leg slightly cocked, head lowered, hands at your sides.

Once I’ve let the horse check out the entrance and it’s time to take it to the next step, I won’t pull on the lead. I’ll simply limit the amount of room the horse has to roam around by holding the loose rope in a fixed position, either against my leg or chest. The horse can move to the end of the rope, but gets no more. He may fight this to some degree at first, but most horses get the idea pretty quickly that the only place they’ll get away from that rope is when they’re looking into the trailer. If at this point the horse begins to resist and tries to turn or spin away, you’re better to back him straight away from the trailer. I don’t turn the horse and walk him around for another go at the ramp, because in doing so I have to release the pressure on that rope for an instant in order to get into position. This release can and will be misunderstood by the horse, and we may be inadvertently teaching the horse to balk. By backing him instead, we maintain pressure on the lead rope. If the horse wants release, he has to find it for himself and we can provide that by using the method I outlined above. This method is okay for the average horse that just needs a moment and some guidance to move forward into the trailer. The trick is to recognize when you’re dealing with a horse that does not trust the handler well enough or has simply decided “I don’t wanna.” The latter is actually easier to deal with, as he will eventually tire of the game and the pressure. But if the issue is lack of trust, the horse needs to be taken back to school, not so much to learn to follow, but to learn it’s okay to follow that particular handler. That’s where the trust/respect relationship comes in. The biggest challenge comes from a horse that is genuinely afraid of the trailer, as we are not dealing with a rational issue. A horse’s fear is seldom a “thinking problem."

I don’t believe it’s possible to make a horse that is afraid of something suddenly overcome his fears. The best we can achieve in the beginning is to show the horse he can be afraid of something but still deal with it without turning on the fear response. This takes time, patience, and consideration for what the horse is going through. You and I know the trailer isn’t going to eat him, but your horse may not be convinced of that. Since we can’t reason with him, our next best bet for that horse is to compile enough experiences in which he is not harmed or threatened, thus outnumbering the bad experience with a series of less stressful ones.

Related: Emergency Preparedness for Horses

Reinforcing the Positive

The one common link between most currently accepted forms of training are the degree and types of reinforcement the horse receives. Experience has proven the two most effective methods revolve around two approaches: well-timed positive reinforcement (horse gets a rub and an “Atta boy!” when the task is completed properly), and creating a scenario in which doing the right thing is easier than doing the wrong thing. In short, we can help our equine friends through the stressful process of learning to trailer by gently praising them when they are successful, and setting them up to succeed in the first place. Release is the single most effective way to communicate success to a horse. One of my grandfather’s favourite sly sayings was, “The best way to thank a horse is to leave him alone.” That’s how riding and training cues work – when the horse yields to the pressure, we take the pressure away. However, in the early stages of training your horse to load, release alone may not be enough. Most horses respond to positive input where they may not even correlate the release of pressure with doing the right thing. Quite often, they are so wrapped up in dealing with the smell of the trailer, the sound the ramp makes when their hoof hits it, and many other new stimuli that simple release is almost lost in the shuffle. I will use release primarily for rewarding forward motion once we’ve made those first steps onto the ramp or step-up, and it’s also very effective to thank the horse for standing still once we’re inside.

A seasoned traveller steps confidently into the trailer.

For the first-timer, the horse that needs to go back to school to unlearn some bad habits, or one needing help to restore confidence after an incident, I’ll take a few extra precautions. For these horses I prefer a longer lead, at least 12 feet. I may also opt for an assistant, depending on the situation. If I do enlist someone’s help, I explain what it is I need them to do and not do. That way we’re always on the same page and no one will get hurt because we were both trying to do something completely different. I find that many owners tend to go to extremes when it comes to praise, at least when I’m around. They will either lavish praise so exuberantly or so loudly as to completely distract the horse; or the praise is almost constant, creating little more than background noise. Be conscious of what you’re reinforcing, when and how much. Saying “good boy” once or twice as the horse sniffs the ramp is fine. Repeating it over and over all the while has less effect than reserving the saying for when the horse has actually made progress. Positive reinforcement is one direct way of telling the horse he’s done well, but the timing of that is important. Too late and the horse may think the praise is for something completely unrelated, but too early can be almost as confusing. As soon as the horse has done what we’ve asked, he needs a moment to make the connection between the action and the praise. Wait for the telltale “licking and chewing” and/or the cycling of the ears before offering that rub (but not a slap) on the neck. With a dermal system sensitive enough to feel a fly landing on a shaft of hair, no horse enjoys being slapped with the flat of our hand. A rub is more effective and a very welcome alternative to that vigorous pat you might be used to doling out.

Unloading is another point in the trailering experience that needs some attention. Don’t just pop the door open and let the horse bounce off. I ask the horse to halt for a moment before actually stepping off of the floor. This reinforces manners, increases safety, and minimizes the chances of injury. Even a moment’s hesitation is fine, especially with a frightened horse. An instant is an eternity to a nervous horse. This is another example of positive reinforcement in that we are now working to prevent or correct unsafe or improper behaviour. It’s a lot easier to train a horse to do this in the beginning than it is to fix it once the horse has created the habit. A horse that bolts off the trailer WILL hurt himself or someone else one day. For safety’s sake, and also to confirm who’s holding that lead rope, I will “make a stand” so to speak. In a step-up, I’ll stand at the threshold and give the horse just enough rope to step off, but no more. This way, he will have to stop and face me once he’s unloaded, and I’m not in the landing zone. A trailer equipped with a ramp may or may not allow enough room for this position. If not, I’ll take up a spot outside, but off to one side of the ramp and out of the path I want the horse to exit. Be mindful; some horses will want to be where you are, so be prepared to direct them along a path you’ve selected instead of in your lap. Note there are two stops involved in unloading: One at the threshold, and the other on the ground.

This horse feels safe and comfortable inside the trailer thanks to patience, time, and positive experiences. Photo: The Biggles/Stock Photos/Photos.com

A Word About Sedation

Using Acepromazine (ACE) or other sedative to tranquilize a horse for transport is risky business, and should never be undertaken except on the direct advice of a competent equine veterinarian. There are far more effective methods to deal with nervous horses while in transit, such as simple training and repetition. Trainers know the only way to properly train a horse for performance is the old “wet saddle blanket” approach; properly preparing a horse for transport should be undertaken with no less care and consideration.

“Ace” slows the heart rate, lowers blood pressure, and can interrupt simple balance the horse needs to feel secure. By drugging the horse we put him at risk of further stress, injury, or even complicating health issues. I also look at such measures as just one more way we unnecessarily complicate situations that can be kept simple by using a bit of consideration for the horse and helping him prepare for what we ask him to do.

Related: Drugs and Your Horse

Related: How to Haul a Horse Safely

Main Photos: Horse - iStock/GlobalP; Trailer - Jebulon/Wiki