What to consider when sending your horse out for training.

By Alexa Linton, Equine Sports Therapist

Along with many people, I've sent my horse away for training with varying results as to its impact.

It is common practice, especially at certain stages of training such as starting under saddle, to invest in several months of intensive training at a trainer’s facility. Given that our horse is going to be in someone else’s care for a substantial amount of time, in a new environment, with countless changes, a great level of care must be given to our decision.

As an equine professional, especially one who specializes in working with trauma, I have seen my share of horrible outcomes arising from situations where a horse has been sent away for training — from extreme illness due to poor, moldy, or inadequate feed, unclean water, neglect, or poor or stressful living conditions, to emotional and physical trauma due to low choice, high pressure, or abusive training styles. Although I know it is sometimes a necessary solution, I would question whether it is possible to bring a trainer into your facility to work with your horse. I have seen many horses far prefer this and benefit from learning in a familiar environment where they are comfortable and relaxed.

Let’s consider sending a horse away for training from the horse’s perspective. First, everything changes in a very short time, often without permission from the horse. This includes their feed, water, pen, neighbours, footing, shelter, and climate, not to mention their human(s). Remember, environment is a huge factor when it comes to equine well-being and nervous system regulation, and it can take time for your horse’s system to acclimatize to something new (even one thing), much less all things changing at once without warning.

Next, add the element of being thrust into learning a bunch of new things all at once. Many trainers are under the pressure of a training window: an agreed upon period of time to train and implement a specific set of skills with your horse. The reality is that most horses, especially young ones, are not prepared or ready for drinking through the fire hose of an often highly pressurized training regimen. A lucky few might excel; a larger number may muddle along, not learning much, returning fairly unscathed but perhaps less trusting; and an unfortunate few will leave the training time worse off than they began, often traumatized and displaying challenging stress behaviours as well as health issues because of the stress.

Related: A Guide to Clicker Training

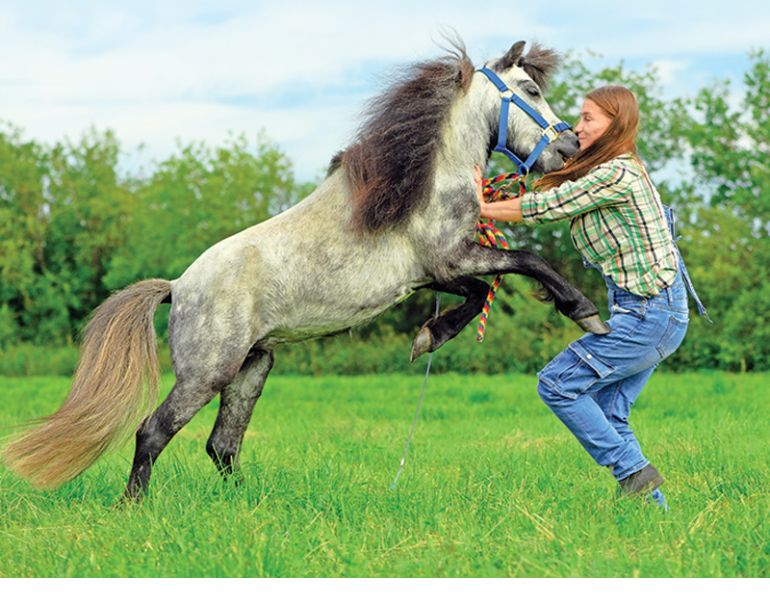

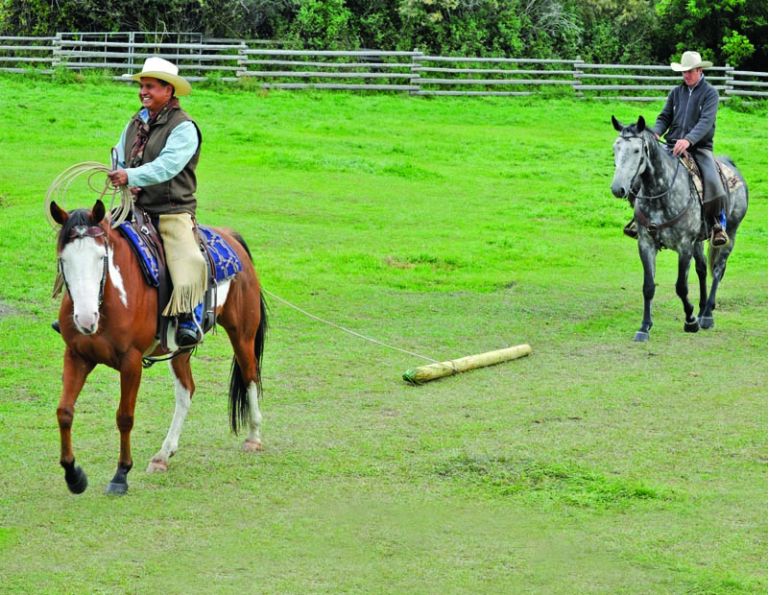

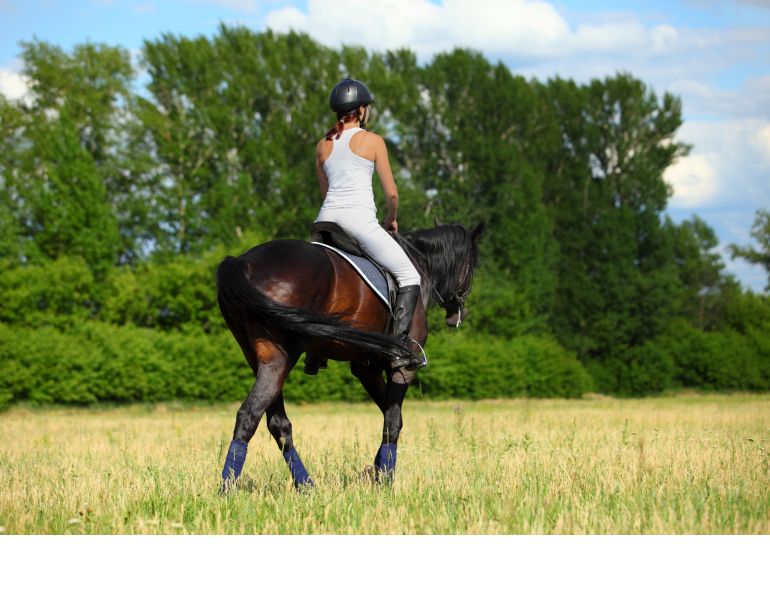

The trainer should be receptive to your attendance at the training facility and to your involvement in the horse’s care during training. Photo: Clix Photography

The way a horse experiences training time depends on the trainer and their training methods and style but, perhaps less obviously, the major responsibility rests with you. The reason is simple: You are your horse’s advocate. Your horse depends on you to make informed choices that ensure he is safe, cared for, listened to, and worked with in a way that works for him, his nervous system, and his unique character. You know your horse best (and if you don’t, you might know who does). As your horse’s person, it’s your responsibility to make sure the environment he is entering supports his well-being and safety. Shipping your horse out to a trainer may seem convenient, but it can be a recipe for disaster if you don’t take the time to become well-informed and get involved.

A lot of things in the horse industry are done because it’s the way others do it, and training is no exception. It’s common to send a horse to a recommended trainer with few questions asked, and without regular contact or involvement. It’s common for a trainer to request that the owner not be present for training sessions and not be overly involved. However, I suggest you get involved and stay involved. From start to finish, be involved in the process with your horse and make sure you are accepted by your chosen trainer as an important part of the process. After all, you also need to learn and grow with your horse, and in the end, your horse will come home and be in a relationship with you. Your involvement creates trust, a sense of added safety in a new environment, and allows you to advocate for ethical treatment of your horse in the training process. Sadly, there are still trainers who will “do what it takes” to get the desired results, even if their methods sacrifice your horse’s emotional or physical well-being. If your chosen trainer is not open to having you present during training sessions, advocating for your horse if necessary, and being involved in care while your horse is away from home, I would argue that these might be good reasons to choose another trainer.

Related: Adventures in Bitless Riding

When considering whether to send your horse for training, here are some questions to ask a potential trainer:

- What kind of hay do you feed? How is it fed (e.g., hay net, on the ground, etc.)? Who does the feeding? What other feeds are used? Will you feed the supplements I choose?

- What is your water source? How often is the bucket/trough cleaned?

- Who is your vet? In what situations do you call the vet?

- Describe the pen or living situation for horses in your care. How big is the space? What is the footing? Is there mud? How often are feet picked and treated? What are your grooming practices?

- What kind of training methods do you use? What is your process for starting a horse? What tools do you use (whip, spurs, rope, etc.)? What do you do if a horse is not responding positively to your tools and methods?

- Are you open to having me at your facility on a regular basis to observe and learn from you? Are you open to my involvement in the daily care of my horse while at your facility? Can I spend quality time with my horse at your facility?

- Will you provide me with references from former clients so I may talk to people whose horses you have worked with?

It is important to visit the trainer’s facility prior to making your final decision. Take note of the condition of fences and facilities for safety, footing, feed storage, and water buckets, as well as overall health and condition of other horses in the facility, which can tell you a lot. Watch some training sessions and take note of the methods and style of training — take some time to “tune in.” Do you feel this situation would work for your particular horse? Does the facility feel like a good place to be? Do the other horses seem happy and content? Do you get a good feeling about the trainer? Our “gut feelings” can give us good feedback when it comes to decisions like these, as they help us connect to what is going to work for our horses. I have learned over the years to always follow my gut instinct when it comes to my mares, and it has helped us all immensely.

One last and important step before you make your decision. Ask yourself this critical series of questions.

- Is my horse’s mind ready? Can he self-regulate without me during times of change or stress? Is he able to respond with relaxation to pressure?

- Is my horse’s body ready? Is he capable of carrying a rider on his spine and over his thoracic sling? Does he know how to push up into the saddle and rider weight rather than collapse through the back? Is he balanced enough to handle the weight of a rider?

Taking things slowly with horses is an important way to support their long-term wellness. Taking one more year to fill in the gaps in your in-hand and groundwork, develop your relationship, and build the horse’s overall coordination, proprioception, and strength is a great idea. Remind yourself that you’re not falling behind; rather, you’re gaining a great deal in terms of the long-term health and happiness of your horse.

Related: Traditions in Horsemanship

It is your responsibility to ensure that your horse is physically and mentally ready for training, and that he will be well cared for at the training facility. Photo: Clix Photography

If you’re feeling good about moving forward after these steps and feel your horse will benefit and be well cared for, be sure to accompany your horse to the facility. Prior to the move, consider creating a contract/document to clarify the agreements made for the care and training of your horse. Plan to stay at the facility until your horse is fully settled and displaying signs of relaxation. Be sure to be present for the first training sessions to ensure the safety and comfort of your horse and create a sense of safety and familiarity. Remember, learning happens when our systems feel relaxed and safe, and this goes for horses, too. It may take a few days, and you may feel like “that annoying too-involved owner,” but this time and presence is essential for a positive experience for your horse. Use this time as an opportunity to connect and establish trust with your horse in a new environment — it’s a great learning opportunity.

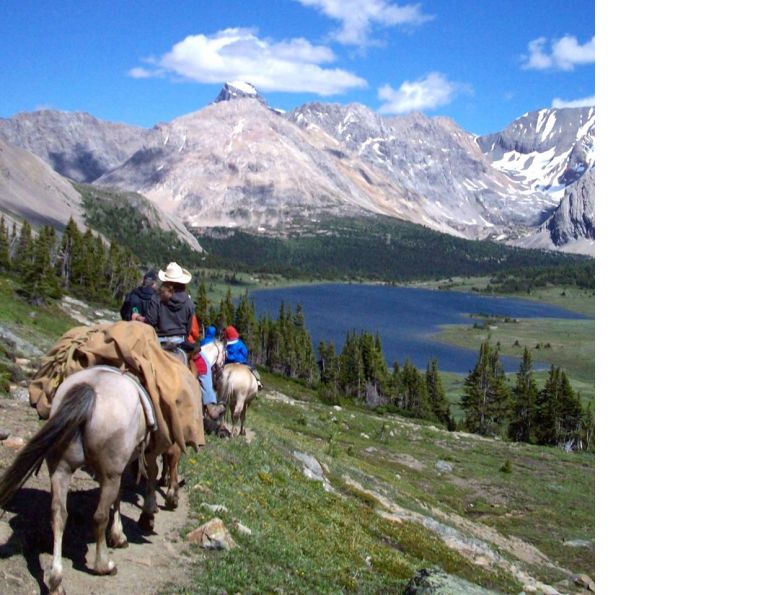

It’s so important to remember your long-term goals when considering sending your horse for training. First, is she physically capable? In the long-term, waiting until she is strong enough to carry a rider through various skills is going to pay off in potentially fewer vet bills and a longer riding career. Is your horse emotionally ready? Maintaining trust and supporting your horse’s growth during change will pay off greatly in future adventures. Is the trainer you are choosing able to care for your horse on all levels during the time away? Making sure your horse spends time with well-resourced and regulated humans is essential to building trust in different humans and in a changing environment. Is the trainer open to you being part of the training process. For long-term outcomes, it makes sense for you to be present and learning, so the skill set your horse is acquiring can be implemented correctly at home. If the environment and the training feel good for both you and your horse, those are positive signs!

Wishing you happy trails and training.

Related: Creating Optimal Learning Environments for Ourselves and Our Horses

Related: Get-It-Done Horsemanship

Main Photo: Shutterstock/Dogist