By Tania Millen, BSc, MJ

Each equestrian discipline has its own specialized movements, requiring distinct training, balance and footwork. While some of these maneuvers may look similar, they serve unique purposes within their respective sports. For instance, in dressage, riders guide their horse’s front end around the hindquarters in elegant pirouettes; ranch riders execute quick 180-degree turns to track cattle; and reining horses perform fast, precise 360-degree spins. Although all involve turning, the reasons and techniques behind these movements are different. To understand their purpose, timing, and differences, we consulted a dressage rider, a ranch horseman, and a reining judge for insight.

Dressage Pirouettes

Pia Virginia Fortmüller is a Canadian international grand prix dressage rider based in Priddis, AB and she says that dressage movements — and canter pirouettes — originated in the military when soldiers needed well-trained war horses for battlefield manoeuvres. A well-executed pirouette meant they could quickly switch from one direction to another. Fortmüller notes, “A good pirouette can be done on a dinner plate.”

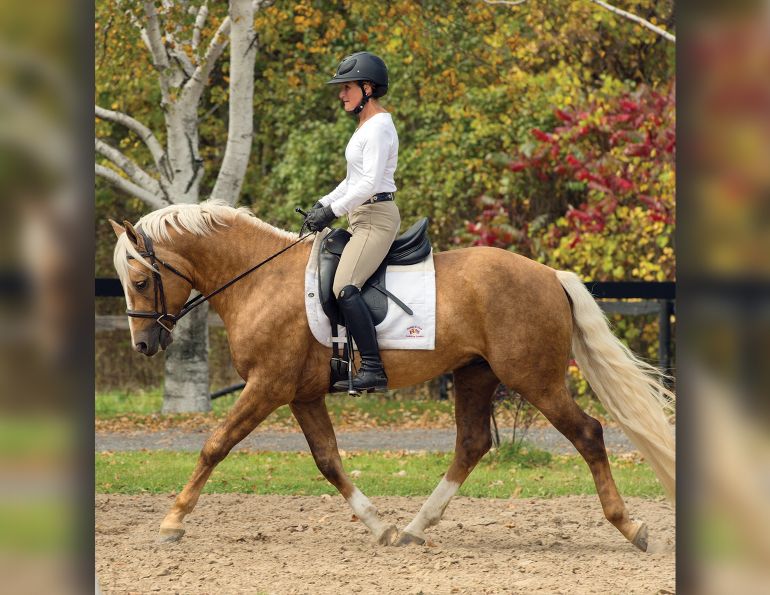

Pia Fortmuller riding Frieda. Photo: Grayt Designs

Related: How to Format Your Horse Ride

But it’s rare for horses to be ridden into war today. As such, dressage has become a foundational training system for English horse sports plus a stand-alone sport in itself. Pirouettes are integral to both. First taught in walk, higher competition levels require canter pirouettes which — along with piaffe and passage — are considered the most difficult dressage manoeuvres.

“A correct pirouette is a very collected canter,” Fortmüller says. “The horse has to hold an immense amount of balance, coordination, and power on one hind leg while bringing their forehand around their hind legs in six to eight strides, starting and ending on the exact same line.”

Canter Pirouette

As described by the Fédération Equestre Internationale (FEI), to execute the canter pirouette the horse must be able to canter almost on the spot with his inside hind leg acting as a pivot, bend and flex the joints of his hind legs willingly and evenly, and show enough body control to maintain an even rhythm, bend, and length of stride without becoming resistant, hollow, or out of balance. The horse must be very fit and strong to turn in place and maintain his regularity of stride. A good pirouette should show the horse with a clear inside bend through the entire body. The inside hind should clearly leave the ground and then land back on the ground in the same place with each stride. The outside foreleg will cross over the inside foreleg but without tilting or weighting one shoulder more than the other, while the outside hind leg doesn’t cross but creates a small circle around the pivoting inside leg. Throughout the movement, the horse should show an unchanged, three-beat, slow (but cadenced) rhythm and should transition in and out of the movement with ease and fluidity. Pictured is Tina Irwin riding Laurencio. Photo: Clix Photography

Top dressage horses can complete two full 360-degree rotations.

“By lifting up over their back and using that power to balance over one spot, we get grace and beauty and elegance,” Fortmüller explains. “Dancing on the spot is the highest degree of difficulty because of the energy needed to keep things going without the horse moving forward.”

She says that canter pirouettes necessitate the horse to hold themselves up in the air, hence require years of strength, power, and endurance training to perfect. She also notes that the horse and rider must trust each other and build a partnership. “The movements can’t be programmed,” Fortmüller explains. For all these reasons, canter pirouettes are considered one of the highest pinnacles of dressage.

Dressage movements such as the pirouette originated in the military and were of great benefit on the battlefield. Photo: AdobeStock/Skumer

Cow Horse Turnarounds

At first glance, the cow horse turnaround may look similar to the dressage pirouette, but there are significant differences.

Keith Stewart is a cutting competitor and rancher who operates The Key Ranch in Longview, AB. He says that cow horses maintain control of a cow by turning through 180 degrees. When a horse is parallel to a cow and moving in the same direction, the cow may decide to stop and go back the way it came in an attempt to get past the horse. As the cow starts to change direction and face the horse, the cow horse begins a turnaround to maintain control of the cow.

Related: 5 Steps to Prep for the Horse Show Test

As the cow starts to change direction and face the horse, the cow horse begins a 180-degree turnaround to maintain control of the cow. Photo: Shutterstock/Vanessa van Rensburg

“Your horse is going to stop, step backward, and pivot on the outside hind,” says Stewart. The horse plants the hind leg that’s farthest from the cow, then backs around the turn, staying faced up to the cow. Backing around the turn is opposite to the forward-moving pirouette.

“You want your horse to rock back — shift his weight back — then step back with his inside hind leg and step across with his front leg,” explains Stewart. If the horse steps towards the cow, that increases the pressure on the cow, which encourages it to speed up. At that point the horse is no longer controlling the cow but chasing it. “You wouldn’t want to move forward because if the horse is going forward it’s easier for the cow to get around him,” Stewart says.

“Depending on what the cow is doing, your horse is going to yield his ribcage [bulge away from the cow] to create a pocket so that the cow can turn without getting pressured by the horse,” Stewart says. This also means the horse’s nose points in the direction of the turnaround and his body bends in the direction of the turn, similar to a pirouette.

The cow horse stops, steps backwards and pivots on the outside hind leg (the leg furthest from the cow), steps back with his inside hind leg and across with the front. The horse yields his ribcage to allow the cow to turn and bends in the direction of the turn, then straightens to go forward. Photo: Shutterstock/Dale A Stork

Once the turn is complete, the horse must straighten out to go forward and continue following the cow. “The horse can’t run if he’s not straight,” says Stewart. “He needs to run into his stop, yield his ribcage, come through the turn with his nose, then straighten out.”

Ideally, ranch and cutting horses will work cows themselves with little input from their riders. That means “cowiness” — a horse’s innate ability to read and anticipate what cows will do — is coveted by ranch and cutting riders. In cow horse competitions, the amount of input riders can provide to their horse depends on the type of competition. For example, in cutting competitions, riders can’t use reins — they use their weight and legs instead. In reined cow horse competitions, riders can use their reins to help direct their horse. When ranching, anything goes, although correct turnaround technique is most effective for controlling cows.

The turnaround is a practical movement still used on the ranch today and it has some similarities to dressage-style pirouettes. However, reining spins are quite different.

Reining Spins

Todd Bailey is an Ontario-based internationally carded reining judge who says reining spins originated when yesteryear’s ranch cowboys got together and informally competed against each other to see who had the best trained horse.

“The spin is based on a working manoeuvre,” he says. “When you’re working cattle, you have to turn really quickly to go after a cow that’s getting away from the herd. That’s pretty much where the reining spin came from.”

But the original ranch-style turnaround, which was described by Keith Stewart, has been amped up for the show pen. Cows don’t do 360-degree turns but reining patterns now require up to four consecutive 360-degree spins in each direction.

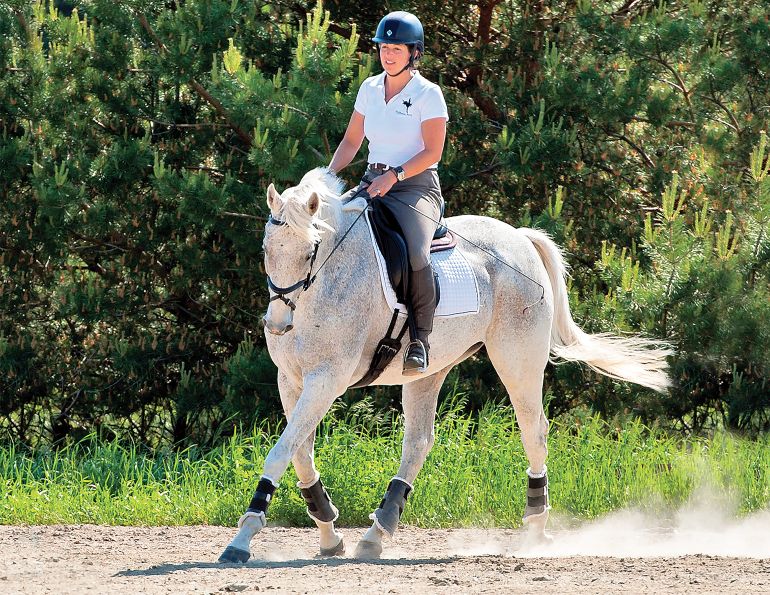

In an ideal reining spin, the horse will pivot on an almost stationary inside hind foot, while the outside front leg crosses in front of the inside front leg and the outside hind leg drives the horse around. It’s a dramatically sped-up four-beat walk which can be so fast that it’s difficult to see what the horse’s legs are doing.

“A lot of reining horses won’t have a pivot foot when they’re turning fast,” Bailey says. “They’ll pick it up, set it down, pick it up, set it down. And sometimes their hind inside foot will travel a little bit.”

Pivoting on the inside hind foot is different from the cow horse turnaround although the forward movement of the spin is similar to the pirouette.

Related: Turn Pushy Horses Around with Three Simple Lessons

In the ideal reining spin, the horse pivots on the inside hind foot while the outside front leg crosses in front of the inside front leg and the outside hind leg drives the horse around. Pictured are Vern Sapergia on Its Wimpys Turn, and Shawna Sapergia on This Chics on Top, both competing at the World Equestrian Games 2010. Photos above/below: Clix Photography

“We want to see a bit of bend in the direction that they’re turning, too,” he explains. “If they’re turning to the left and their nose is to the right, then their shoulder isn’t going to be moving properly. So that’s incorrect.”

Bending in the direction of the turn is also necessary for dressage pirouettes and cow horse turns.

Bailey says that reining horses really use their front end while their outside front leg and outside hind leg drive them around into faster spins. Cow horses can also turn very quickly, but pirouettes can look like they’re occurring in slow motion due to their extreme collection.

The footfalls of the reining spin can be so fast it’s not easy to see what the horse’s legs are doing. Photo: Clix Photography

In comparing cow horses and reining horses, Bailey explains, “A cow horse is going to be a little more upright in the front end because they have to be ready to go after a cow, whereas reining horses are more for show so they can have lower neck sets.”

Softness, cadence, correctness, and suppleness are desirable in reining spins, too. “Once we have that, the speed comes,” says Bailey. “A lot of horses are trying to get the speed before they get the correctness.”

Because reiners ride with one hand, they ask the horse to spin by neck reining and follow that up with an outside leg aid. “The horse builds speed then they shut off [stop spinning] in the blink of an eye,” he says. The centrifugal force created by the spin means riders must be balanced — centered — in the middle of their horse. “If they’re leaning to the outside, they’re probably going to get left behind and find themselves falling off,” says Bailey.

Falling off isn’t something dressage riders are generally concerned about during pirouettes but it’s certainly possible when riding a cutting horse. Regardless, there are obvious differences in how horses are required to “turn around” in different sports. Dressage pirouettes, cow horse turns, and reining spins are all speciality moves which require specific foot placement, athleticism, and training. These three movements also illustrate how historical horse use impacts equestrian sports today and the impressive versatility of horses.

Related: Counter-Canter: What's the Point?

Related: Are You Riding All Your Gears?

To read more by Tania Millen on this site, click here.

Main Photo: Keith Stewart. Credit: Alex Callaghan Photography