By Lindsay Grice

Q: I have done most of the training on my four-year-old gelding myself. He will yield off my leg, do a turn on the haunches, and collect his trot to a jog. I just can’t seem to slow his canter down. When I try, he just breaks into a trot. How do I keep it together?

A: You were on the right track when you used the word “together.” As you have discovered, pulling on the reins will only cause your horse to fall out the back door into a trot. So, how do we shorten a horse’s stride while keeping the canter rhythm going? Put simply, by using the brakes and the gas pedal in unison. Initially, this may seem counterintuitive to the equine mind, but if we use the process of “shaping,” we can teach our horses any skill with less stress.

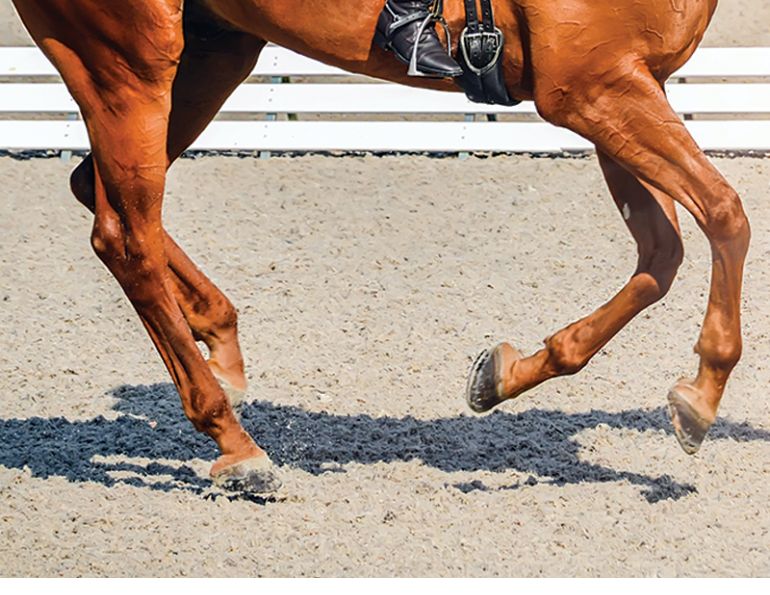

First, let me remind you to keep your expectations realistic. Not every horse is physically capable of loping slowly enough to be a competitive Western pleasure horse. Horses that are suited to Western pleasure are shorter in stride, don’t have much of a natural motor, and WANT to lope slowly more often than not. Asking your horse to travel at a pace he can’t deliver with quality is like trying to fit a square peg into a round hole, and the result will be an artificial, four-beat canter. However, any horse can be asked to slow his rhythm and compress his canter within a certain range.

Get Your Tools

Having the right foundation in place before you build is key. Likewise, you need to have specific tools before asking your horse to perform this type of work. It’s great that your horse already knows how to yield laterally to your leg, as this is one of the necessary tools. You should have control of your horse’s hips as well; a horse that fishtails his hips to the outside of the track will be unable to compress his stride. Start with turn on the forehand work to teach him to keep his hips straight and underneath of his body. Make sure your gas pedal is working: the horse should go forward immediately when asked, every time, everywhere. Finally, ask yourself if he flexes and gives to any pressure from the bit, or if he resists, crosses his jaw, or raises his head?

With these tools available, when you send the horse forward into the resistance of your hands, he will collect his frame and give to the bit, rather than spill out the back door.

Shaping

Shaping, in learning science, refers to gradually teaching a new behaviour through reinforcement until the target behaviour is achieved. Have you ever played the “Hot and Cold” game? As the player gets closer to the prize, you yell “Hotter!” telling him that he’s on the right track. When my horse is on the right track, I reward his approximation of the behaviour. I call this rewarding the thought, or rewarding a try.

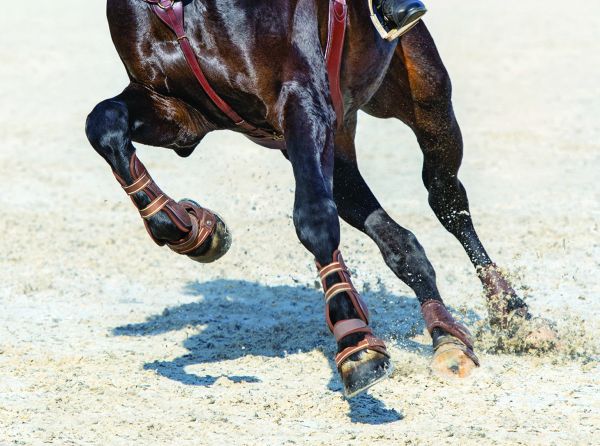

“Shaping” refers to using positive and negative reinforcement to achieve a desired behaviour. When you first begin teaching your horse to slow, or collect, his canter, reward his every try and block his evasions. Photo: Robin Duncan Photography

Sometimes the right try happens by accident, as if the horse is guessing. When teaching your horse to shorten his canter stride, reward him at the moment he starts to shift his weight back in an attempt to collect. Many horses respond at first by raising their heads, speeding up, or breaking to trot. Your job is to block all the wrong tries and reward the right ones.

Back to the Box

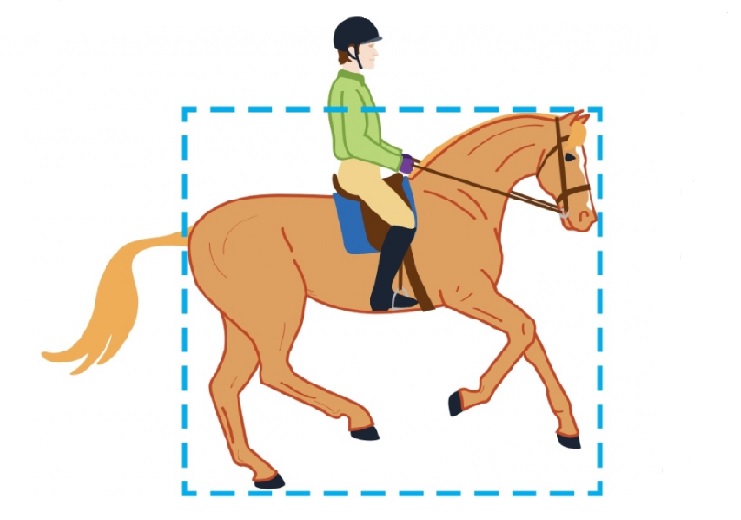

Picture a three-dimensional box around your horse. To slow the canter, you must resist every time your horse lengthens or quickens his stride (picture him meeting the front of the box), while maintaining the canter rhythm with your leg and seat (the back of the box). Provide freedom every time he slows his stride (in the box).

Picture a three-dimensional box around your horse and shape his canter to fit "within" the box.

Your horse will eventually see a pattern developing and will seek the freedom of remaining in a slow canter. This sounds simplistic, but it’s pretty common to see a rider hanging on her horse’s mouth, tug of war style, while he motors around, oblivious to her.

Motivation

It's important that the resistance you use to slow your horse is enough to get his attention. When slowing your horse, establish firm contact by sliding your elbows back, with hands directed in a straight line toward your hips. Your hands will be closed into a fist, but avoid a cement-like feeling which will frighten the horse and make him eager to escape your contact.

If the fingers of one hand remain a bit sponge-like, your horse will give to the pressure, not flee from it. Keep it up until your horse acknowledges you by yielding or flexing his jaw and compressing his stride, even a little. He may try many escape routes – head up, head down, break to a trot, etc. – but relax your muscles only when you feel him take a smaller canter stride. Reward him immediately by allowing your arms to flow with the motion of his head and neck.

Timing

Your horse won't recognize the pattern of resist-and-release unless your timing is absolutely consistent. Having a ground person is especially helpful. When I’m teaching, I ask riders to let me ride through them. I watch very carefully, calling out “resist” when the horse tries an escape route, followed by “release” the moment the horse nails the right answer. Eventually, through consistent use of the shaping process, your horse will learn to slow his canter.

To read more by Lindsay Grice on this site, click here.

Main Photo: River Bend Designs - Be realistic in your expectations; not every horse is physically capable of loping slowly enough to be a competitive Western pleasure horse.